This is a non-romance, romance, which is usually a paid subscription feature where I write about something other strictly romance novels. I changed what I was doing with this series this month, so this one is free.

When I first saw Husbands by John Cassavetes I certainly thought about One Direction because I watched it in July 2020 when the only album I was listening to was Heartbreak Weather by Niall Horan. When I heard the news of Liam Payne’s death on Wednesday, I thought about my relationship to the five men who were in the band and saw that my complicating feelings were different than many people who were talking about their relationship with the band and my brain went back to Husbands.

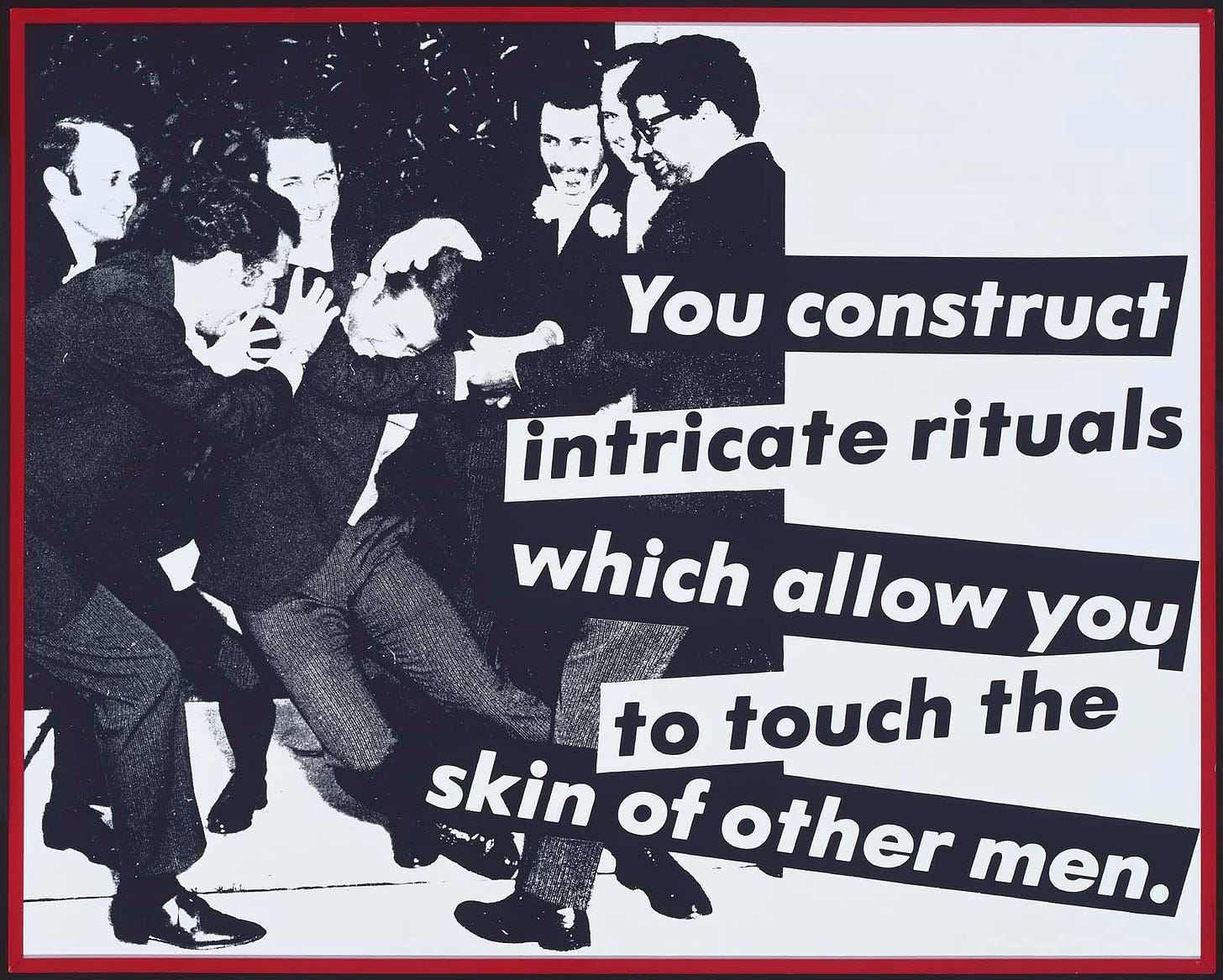

Two’s company, three’s a crowd, and four or more men, if they’re photographed hugging each other enough, are a boy band. Liverpool F.C., The Beatles, most sets of groomsmen. I’m less concerned about what the men do in this group as a qualifier to be a boy band than I am about my reaction to viewing them. The Beatles are a boy band because I had to turn off Get Back when I thought they were being too mean to George. While looking at these men, I want to watch them be friends and work together, to have the option to fall in love with them as a unit, and for their affection for each other to be a proxy for my own toward them.

And when the relationships sour or turn or complicate, I feel betrayed and then guilty for feeling any possession over affection that was never really mine to own, though it was certainly sometimes performed in part for my benefit.1

In Husbands (dir. John Cassavetes), the boy band of suburban, married professionals is down one member. Stuart Jackson has died suddenly and the film opens with his funeral. His three best friends, Gus (John Cassavetes), Harry (Ben Gazzara), and Archie (Peter Falk) deal with, or more accurately, ignore or cause the fallout as they avoid processing his death. All the men are married, ostensibly happy, and shown smiling photographs in the film’s title sequence, but after Stuart’s death, they can’t seem to make their way back home after the funeral. They wander around New York, conversations sliding past anything of substance or close to processing their loss. They are frequently silly together—the film’s tagline is “a comedy about life, death and freedom.” It is easy to fall in love with the characters in the first sequence of scenes as they flit about New York, drunk for a couple of days, played by three actors who were real-life friends. There are microexpressions of available charm and glances of shared love as a constant in all three actors’ on-screen presences, no matter what the characters are doing on screen.

But what is also present in Husbands is a constant threat of cruelty and disgust that these men exacerbate each other’s worst tendencies. They mock and yell at strangers and when I watch, I tense up, looking at the people on the edges to read if this is the moment that the dam is going to break, or if everyone is still taking it in good, drunken humor. As the men move around in their grief, first in New York City and then momentarily back in their suburban lives, and finally in London, on a runaway vacation, they wield masculine camaraderie like a cudgel, knocking down women as they collapse in on their group, holding each other tighter and tighter.

The characters’ indifference to the feelings of their wives and the female strangers they meet makes the film a hard watch, where I am thrown between warmth at their competitive, violent love for each other and the knowledge that I am infinitely more likely to be the butt of a joke shared between these husbands to mostly off-camera wives than be a recipient of the depressing glow of understanding they share in their unspoken grief.

The easy misogyny of the characters is also an easy way to discard the film as hateful or cruel itself. But I mostly just find it achingly sad to watch these men mourn in a way that demands that they never cry or reminisce. Sad for them and sad for the women they abuse on their way and especially how they talk about the women to each other. After each has furtive attempts to have sex with a stranger that they meet at a London casino, each man embarrasses his partner in turn. But when reporting the encounters to each other, Archie and Gus declare their love for the women, even as they describe them in exceedingly cruel ways to each other.

Stuart, the dead friend, is brought up barely in the film, but a much hackier film would have Harry, the character whose home life is falling apart the most concretely and who seems the most untethered by the loss of the group’s glue in Stuart, perhaps break down in asking for comfort from his friends. Instead in the last sequence of the film, Gus and Archie leave Harry in London. They each entertain the fantasy of never going home again too, but when confronted with Harry’s plaintive looks suggesting they extend the party/crisis forever, Gus and Archie realign and insist that they go home. But Harry is not on the plane when we see the pair returning to America.

Outside their suburban homes, Archie asks “What’s he gonna do without us?” and repeats himself, but Gus never gives an answer. Instead, he walks into his yard to greet his children. His toddler daughter cries at his appearance, and his preteen son (played by John Cassavetes’ son, Nick, director of The Notebook) asks his father where he’s been.

I’m just outside the intended demographic of One Direction. I’m four days older than Louis Tomlinson, the oldest member. I don’t really associate the band with my “girlhood” and I don’t think I am mourning a lost youth with the recent death of Liam Payne, which has been a theme of some social media tributes. But I loved them from the jump. These were not boys that were marketed to me to have crushes on, but I immediately saw the appeal of the behind-the-scenes, home movie content that pumped out from them, along with non-stop releases of music and tours. (Five albums in five years and they are long albums.) In this material, we didn’t just see the archetypes of the boys, packaged for interviews or teeny-bopper magazine photoshoots. We saw them at play with each other.

The spontaneity of their affection also played out in their concerts, newly able to be filmed and disseminated, and reedited into fan edits on their fans’ smartphones, in a way that their boy band precedents escaped. One Direction, famously, can’t really dance. Any choreo they did during concerts or music videos was perfunctory and almost laughing at themselves. Instead, their movements around the stage seem driven by their interest in playing, making jokes, and rough housing together.

In the years since the band went on hiatus, the theme of most revelations about boys’ time in the band has seemed to be that it was not always easy affection. That the goodness and joy, at least as we saw it, was a packaged product, first made by producers and executives controlling the output, but then repackaged and reframed by the community of fans to create narratives of the intricacies of these friendships, as if they could be knowable to anyone outside of them.

Liam Payne died on Wednesday and he has been and will continue to be eulogized, dissected and mourned, particularly as elements of his story suddenly reach a wider audience. The parts of the internet that talk about One Direction had already been talking about Liam in the past two weeks and the tone was primarily judgmental. He has flown to see former bandmate Niall’s concert in Buenos Aires and his behavior at the concert, including taking photos with fans was contrasted with Harry Styles’ more subdued and private behavior when he went to go see Niall earlier on tour. Harry was cool, Liam was cringey.

This juxtaposition was coupled with Maya Henry, Liam’s ex-fiancée, speaking more openly about things long suspected, specifically confirming an altercation during the band’s tenure that Liam had anonymously referenced had been between Liam and Zayn Malik and confirming some of the emotional manipulation and abuse that she used to inspire her book, Looking Forward, published earlier this year.

For some people posting responses to Liam’s death, these revelations happened at the same time. People who had large affection for the band, but maybe hadn’t kept up with the rumor rumblings of Liam’s actions or the extent to which he had spoken about struggling with drug and alcohol addiction. I saw social media posts where people attempted to square their outbursts of sadness with the perception that Liam was a “bad person,” justifying either through mourning the boy who he was, or the boy who they thought he was, the parasocial veil lifted to reveal a real, flawed and troubled person, compounded with the mourning of his life.

I wanted to write about Liam for Restorative Romance because of this tension and the gap between the conflicted feelings I saw demonstrated and my own. Part of being an abolitionist that I try to enact in my everyday life is that I resist the impulse to categorize any person as a bad person. I believe that are harmful acts and we should try and minimize those acts and the impact of those acts. I’ve gotten responses to articulating this belief before it’s a cop-out, too easy or neat, or too contrarian.

But by enacting this belief, I also have to adopt the corollary. There are no good people, incapable of harm. There are compassionate and kind and helpful actions and those can and will exist in a perpetuator of harm. Sarah Lamble writes in “Practicing Everyday Abolition,” a chapter originally published in Abolishing the Police: An Illustrated Introduction, “Too often we are invested in aligning ourselves with the good and the innocent, and in distancing ourselves from the guilty and the harm doers. Everyday abolition requires us to acknowledge we are all capable of harm just as we are all vulnerable to being harmed. This doesn’t mean that the distribution of harm is equal; we know that harm and violence are deeply connected to structures of power that render some bodies more vulnerable than others. But we must understand our role in enabling or upholding structures of power that produce violence and impact on the distribution of life chances.”

The contradictory feeling I had when I heard the news of Liam’s passing was guilt. For being one little bit of the circumstances that thrust him into some fame and riches, but also the hurt and pain, both that he experienced and that he perpetuated. It is not so much guilt that I can’t go forward or rationally understand that I, or any one fan, is trace evidence on his story or how end it ended. But when I have been thinking about the joy I derived as a viewer of his life and his work, I think about it in terms of something that was extracted from him.

The same micro moments of affection that were played over and over again that created a mass collective mental image of a man that a real person could never line up with are now being repackaged to memorialize him. “Fans block paparazzi from being able to take photos of Liam’s father in Buenos Aires” is a bit a chicken and an egg situation, isn’t it?

I think I’m partly so enamored with examples of men showing affection to each other because I am necessarily a voyeur to these relationships. In Husbands, I land on knowing that these characters love each other, but that love will always be circumscribed by the rot of their circumstances—not to excuse their cruel behaviors, but to mourn that that affection I’m so moved by grows out of shared hate and pain. It’s the same that makes me cry any time Al Pacino and John Cazale are together on screen in The Godfather. Cassavetes’ pulls back the structure and performance that is inherently surrounding any of views of male friendship that I have access to. The form of the film, with extremely long scenes and people talking over each other in a script that is almost impossible to quote from in order to explain what is happening because context is so often given through touches and glances, has been derisively compared to a home movie.

In the case of One Direction, I have the guilt of associating unbridled and uncomplicated joy with something that caused someone pain, especially now that Liam’s life has been cut short. It will always be tragedy, where complicating factors of his work and his relationships will be read in light of how he died. But even still, the thing that has made me weep the most in the past two days were the tributes posted by his band members, not listening to the music, the supposed work product of the band.

But the Husbands form condemns me as the viewer too. I’m peeking in, taking scopophilic pleasure as moments that I would not be privy to, but I am also punished with my disgust and anger at the juxtaposed casual cruelty that would also normally be behind closed doors. And the big pill to swallow is that one reality does not negate or clear my feelings about the other.

I’m thinking specifically about how I’ll feel if Trent Alexander-Arnold signs with Real Madrid.

this was so lovely - I had the same thought about the fans and the paparazzi in Argentina... I was moved/relieved to see Zayn push his tour back to grant himself some time.

this was really beautifully written ❤️ not a 1d fan but i always get a little caught up in the spectacle of grief and you gave me a different lens to think about it.