I’ve decided to do Saturday updates on Ulysses until I finish it. I’m finding myself rereading things a couple times before I move on, so no idea on the timeline. But this commitment will get me reading something Ulysses related every week until I’m done. I’m also reading the Richard Ellman biography of Joyce and The United States of America v. One Book Entitled Ulysses by James Joyce, a collection of primary sources about the lead up and fall out of obscenity trials that banned and then permitted the publication of the book in the United States. The Most Dangerous Book: the Battle of James Joyce’s Ulysses by Kevin Birmingham was also recommended by a Restorative Romance reader and it’s on the docket.1

I don’t actually have that much to say about Ulysses thus far. The most notable reaction is that I’ve had a compulsion to repeat out loud to myself a few turns of phrase, particularly those using alliteration (“wavewhite wedded words”). Apparently this is a common phenomenon amongst readers (“jejune jesuit” seems to the episode one alliteration that everyone gets cheeky about). At the time of writing, I’ve only read the first episode (three times), untitled in the text, but given the title “Telemachus,” from the schema that Joyce provided as explanatory notes to friends.

Other than the joy of repeating myself to my dog as I read,2 I also love how dependent the book is on the geography of Dublin. I knew about this feature before going into it, just from the culture around the book—walking the book’s plot on Bloomsday and what not. I love when a book has impeccable geography, particularly in a city. I love when non-fiction books mention street names and I can pull out a map and I especially love when a novel does it well. Since Stephen Dedalus has just stepped out of his home where I am at in the book, I’ll save further thoughts on this for once someone gets on the road in Ulysses.

On the first page, the “Telemachus” episode put into mind the most famous chapter in A Room with a View because everything in the world reminds me of A Room with a View. In Ulysses, protagonist Stephen Dedalus lives in a tower in Dublin with Buck Mulligan. The opening episode involves the men being at the top of the tower and working their way down and through the building until Stephen decides to exit and start his day. Buck begins the day by shaving his face, performing a blasphemous liturgy and mocking Stephen while doing it. But he does his morning ablutions by setting up his equipment on a parapet of the tower.

He pointed his finger in friendly jest and went over to the parapet, laughing to himself. Stephen Dedalus stepped up, followed him wearily halfway and sat down on the edge of the gunrest, watching him still as he propped his mirror on the parapet, dipped the brush in the bowl and lathered cheeks and neck.

The parapet is a part of the tower’s defenses, a short wall for soldiers to lean over and shoot from. Later Buck leans over the parapet and encourages Stephen to look out at the sea.

He mounted to the parapet again and gazed out over Dublin bay, his fair oakpale hair stirring slightly.

—God! he said quietly. Isn’t the sea what Algy calls it: a great sweet mother? The snotgreen sea. The scrotumtightening sea. Epi oinopa ponton. Ah, Dedalus, the Greeks! I must teach you. You must read them in the original. Thalatta! Thalatta! She is our great sweet mother. Come and look.

Stephen stood up and went over to the parapet. Leaning on it he looked down on the water and on the mailboat clearing the harbourmouth of Kingstown.

Buck and Stephen are misaligned and the opening of calling the sea their mother invites Buck to remind Stephen of his dead mother, a sore spot between the friends.

A lot of writing and talking about Ulysses emphasizes the structure of the novel in these episodes. People rank all 18 of them—this feels like a wild enterprise for most novels. Readers of War and Peace will talk about Prince Andrei looking up at the sky at Austerlitz, but it’s really just one paragraph, and the whole battle takes ten chapters.3 And I know the chapters around the scene have to be less Big and Moving because I have to know where the armies are in the battle. It isn’t that they are worse; it’s that they are prose and plot, designed to prime for the poetic reaction that I have to Andrei getting shot and looking at the sky:

“What’s this? Am I falling? My legs are giving way,” thought he, and fell on his back. He opened his eyes, hoping to see how the struggle of the Frenchmen with the gunners ended, whether the red-haired gunner had been killed or not and whether the cannon had been captured or saved. But he saw nothing. Above him there was now nothing but the sky—the lofty sky, not clear yet still immeasurably lofty, with gray clouds gliding slowly across it. “How quiet, peaceful, and solemn; not at all as I ran,” thought Prince Andrew—“not as we ran, shouting and fighting, not at all as the gunner and the Frenchman with frightened and angry faces struggled for the mop: how differently do those clouds glide across that lofty infinite sky! How was it I did not see that lofty sky before? And how happy I am to have found it at last! Yes! All is vanity, all falsehood, except that infinite sky. There is nothing, nothing, but that. But even it does not exist, there is nothing but quiet and peace. Thank God!...”

But I do love a good chapter. I reread my favorite books frequently, but usually when I say that, what I mean is I’m picking up somewhere in the middle and reading the stuff in and around my favorite chapters. So in lieu of anything interesting to say directly about Ulysses yet, let’s talk about my favorite chapters, many of which I’ve linked to before in this newsletter.4

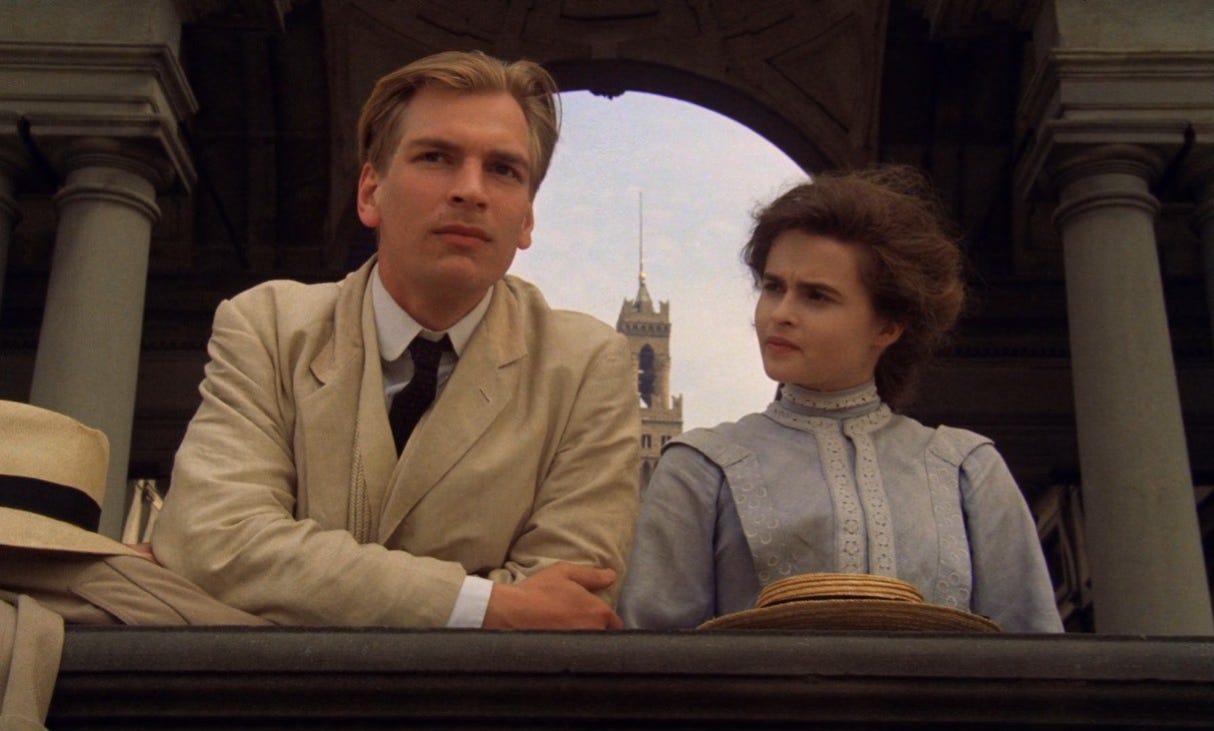

Some of my nerves about not “getting” Ulysses dissipated when I realized that Joyce would use the word “parapet” six times in the first episode. Even if I didn’t get anything else out of it, I could trace and hang onto that little wall. I love the word because of its importance in my favorite novel, A Room with a View. Other than Moby-Dick (which I’ll get to in a second), A Room with a View has my favorite chapter structures in literature. When EM Forster decides to break and how he opens his chapters, often with his blithe, very British, limited third person narration before he falls into alignment with his heroine makes each one feel like opening the drawer of a jewelry box. He also titles them beautifully, but the best chapter is named very neutrally.

“Fourth Chapter” is about as perfect as chapters get in literature. Two chapters in the book get this titling convention: this one and the one where Lucy, her mother and Cecil happen upon George Emerson, Freddy Honeychurch and Mr. Beebe bathing in a pond. Every other chapter has a illuminative name. These simply numbered chapters are the major catalysts that trigger George to be moved to kiss Lucy twice and turn her world upside down.

This chapter has the scene where Lucy buys postcards and then she and George witness the murder in the Piazza della Signoria. She faints and her postcards fall in the blood. George ushers her away from the scene and throws her postcards into the Arno as the couple leans on the parapet over looking the river. It’s the first time they are alone together, without any Victorian hauntings in the form of chaperones, and they experience something Big (the murder) without having any guidance of how to react. Untethered by convention, their bodies mirror each other in their attitude, leaning over the parapet to the look the Arno together, unsure of exactly how to proceed: “She stopped and leant her elbows against the parapet of the embankment. He did likewise. There is at times a magic in identity of position; it is one of the things that have suggested to us eternal comradeship.” George will move forward by kissing Lucy later on the hills of Fiesole and Lucy will then retract into herself and England, until she is later spurred to explore the romance again.

Well, thank you so much,” she repeated, “How quickly these accidents do happen, and then one returns to the old life!”

“I don’t.”

Anxiety moved her to question him.

His answer was puzzling: “I shall probably want to live.”

“But why, Mr. Emerson? What do you mean?”

“I shall want to live, I say.”

Leaning her elbows on the parapet, she contemplated the River Arno, whose roar was suggesting some unexpected melody to her ears.

Another perfect chapter, to me, is an antecedent of the whole first half of A Room with View, since it is Dorothea Brooke’s honeymoon to Italy with Mr. Casaubon in Middlemarch, but specifically the scene where Will Ladislaw first sees her in the Vatican Galleries. It’s Chapter 19 and it opens with an epigram from Dante: “L’altra vedete ch’ha fatto alla guancia, Della sua palma, sospirando, letto.” or “Behold the other one, who for his cheek, Sighing has made of his own palm a bed.” The epigram references the experience Will has of looking at Dorothea as she looks around the gallery: she holds her hand on her face, with a thousand yard stare, not quite looking at art, but suddenly aware that she is looked at. It’s the first interaction we see between Will and Dorothea and that it takes place in a gallery of nude bodies, that the narrator emphasizes the English tourists would struggle to understand in their time period (pre-dating the boom of guidebooks, that tourists a century later would rely upon, like Lucy Honeychurch in A Room with a View).

There’s another scene in Middlemarch that I love because it is reminiscent of my first favorite chapter of all-time. In the opening of the book, we meet Dorothea and her sister Celia and they go through their mother’s jewels, deciding which of the baubles they will keep as mementos. Celia is interested in the jewelry and Dorothea attempts to be puritanical about it, though she is attracted to a set of emeralds eventually. The sisters’ reactions to the jewels in the box set up their personalities and dynamic efficiently. But I love that chapter because it reminds me of “Amy’s Will” from Little Women.

I was in a perpetual state of reading Little Women from ages eight to fourteen. I would pick up the chapters I liked best and reread them, infinitely. Though I always identified as Meg (boy crazy oldest sister), my favorite chapters usually were the ones focused on Amy, for whatever reason. I don’t think I’ve read anything in my life as often as I’ve read “Amy’s Will.” Amy has been sent to spend time with Aunt March, a separation that will shape the March sisters’ relationships to each other forever, since Amy will become a favorite of the rich aunt.

Amy and Estelle, Aunt March’s maid, look through a cabinet of jewels. Estelle suggests that Amy will get a turquoise ring in her aunt’s will and this inspires Amy to write her own will. The result is a charming legal document that only a 13 year old youngest sister could write, where she bequeaths her limited possessions to her family and friends, while getting in a few pointed remarks. (“To Jo I leave my breastpin, the one mended with sealing wax, also my bronze inkstand—she lost the cover—and my most precious plaster rabbit, because I am sorry I burned up her story.”) When Laurie reads it, he assumes Amy’s been told about Beth doing something similar. The significantly closer to death, and significantly less litigious, Beth March hasn’t written a will, but she has told her loved ones which of her possessions she would like them to have. Amy ends the chapter “with streaming tears and an aching heart, feeling that a million turquoise rings would not console her for the loss of her gentle little sister.”

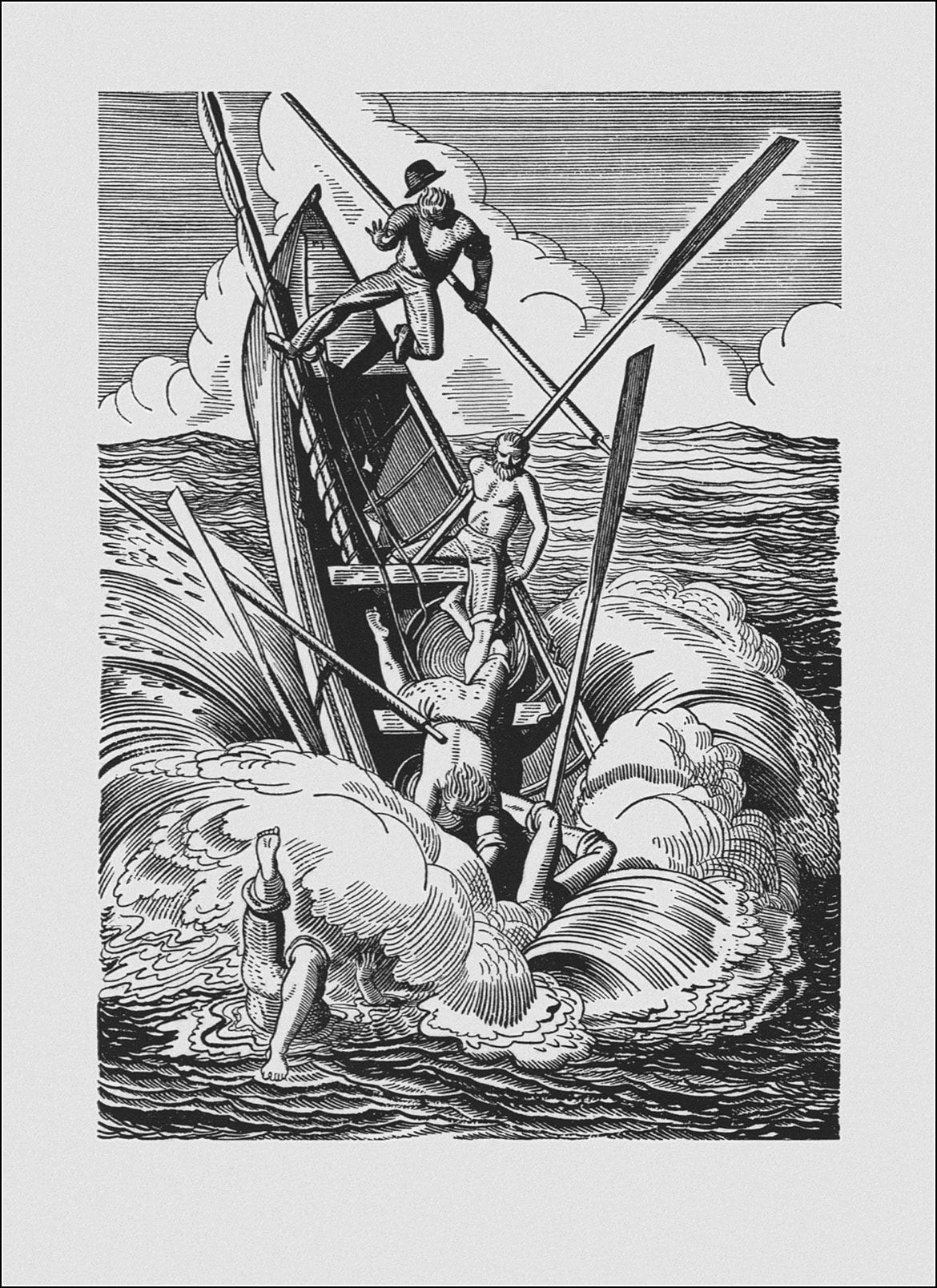

Moby-Dick has the best chaptering of any book ever. I don’t know what to tell you. The way Melville controls your attention is why I was able to attack and finish this book during a hospital stay, during which, for all intents and purposes, I should have been completely distractable/distracted. Maybe not the best or even my favorite, but The Pulpit, which comes pretty early was when I knew my brain was changing while reading the book. Ishmael has entered church and he is waiting for the sermon to start. The minister, Father Mapple, enters and Ishmael relates his history as a sailor himself. As he is looking and describing the pulpit in detail, Ishmael begins to think of the pulpit as the front of a ship.

What could be more full of meaning?—for the pulpit is ever this earth’s foremost part; all the rest comes in its rear; the pulpit leads the world. From thence it is the storm of God’s quick wrath is first descried, and the bow must bear the earliest brunt. From thence it is the God of breezes fair or foul is first invoked for favourable winds. Yes, the world’s a ship on its passage out, and not a voyage complete; and the pulpit is its prow.

The chapter is short, less than a thousand words. But the God talk gets to me. There’s lots of God talk in Moby-Dick, I just remember my body’s reaction to this chapter pretty acutely, rereading paragraphs out loud before I moved on, a habit I’ve fallen back into with Ulysses.

Please tell me about your favorite chapters or if this is how you reread books. Are you starting at the beginning every time? I am realizing that I think of getting to choose when parts I read on reread as a reward for “finishing the book” the first time.

I forgot to recommendations in the last newsletter, so here’s a bunch.

Reformed Rakes did two whole episodes on Fabio, but Chels’ research was so exhaustive and they’re so smart, I am still always so excited to read their takes on this cursed enigma of a man. This piece at the

is about Fabio, but also about Chels’ relationship to romance cover art, which bucks the main narrative and received wisdom of Romance Think Pieces.™ is on Youtube again! Beth and I watched Mel’s return to long form video essays together when we were in Salt Lake City and I’m pretty sure Mel is the only person I ever want to do meta discourse about Tiktok, ever. That is only part of what they are talking about! But they are very good at it. on shipwrecks! One of my reactions on Election Night was to call my mom, who still lives in Georgia, and tell her I was moving home from Philadelphia. Kind of a rash decision to make on a Tuesday night while sobbing and one I was talked down and out of pretty quickly. But the feeling of being stuck meant I wanted to be stuck with my family. Haley’s love of shipwrecks (and her home in Florida, which peeks through in all her writing) captured that.The next big romance theme of this newsletter is going to be medievals, which somehow, without intention became a huge theme of my reading year: One Burning Heart by Elizabeth Kingston, By Possession by Madeline Hunter, Keeper of the Dreams by Penelope Hunter, Saving Grace by Julie Garwood were my favorites this year. For My Lady’s Heart and Shadowheart by Laura Kinsale are old favorites.

Sometimes I say things and I’m burdened with the knowledge that just as I can usually tell when I meet a stranger in the wild that they’ve gone to law school, they are also clocking me.

Named Steve, not after Stephen Dedalus, but when I am reading Ulysses, I am finding myself thinking of this protagonist in terms of my terrier. I’m always looking for terriers in literature and movies.

The best chapter in War and Peace is when Andrei goes back home and sees his pregnant wife dying in childbirth and asks for her forgiveness. After he is kicked out of the room, he hears a baby crying in the room and thinks “What have they taken a baby in there for?…A baby? What baby...? Why is there a baby there?”

These are passages that I revisit so much, I often think of then when I reading something else, so when I write about something else, I have the tendency to just link to the underlying chapter on Project Gutenberg.

When rereading I am also usually just rereading my favorite parts and the sections directly before and after them -- depending on the book and my mood that might just be a favorite scene or a favorite chapter. For Pride & Prejudice it's most Darcy/Elizabeth interactions, for example. I rarely reread for pleasure by starting at the beginning again; that's usually reserved if I need to make sure I have all of it fresh in my brain for some kind of upcoming discussion or read-along etc.

I also was constantly rereading Alcott books (primarily Little Women, An Old-Fashioned Girl, Eight Cousins/Rose in Bloom and certain bits of Jo's Boys) during those ages but the part I reread the most in Little Women was Amy's trip to Europe and especially Amy and Laurie's interactions there. If I feel emotional and need to make myself cry I can reread the chapter "The Valley of the Shadow" and INSTANTLY start sobbing.

I rarely pay attention to chapters - I think they’re one of those things I only notice if they’re done poorly, like sports officiating - but I’m reading a chapter a day of Les Mis this year and the title of the other day’s chapter was “The Dead are in the Right and the Living are Not in the Wrong.” It gave me chills, and the chapter absolutely lived up to the name. It was focused on why the people of Paris didn’t rise up and join the barricades and included the phrase “sometimes the stomach paralyzes the heart” which is currently living in my head rent-free.