Francesca da Rimini in Dante, Tchaikovsky and Sturges

medieval cheaters, bad husbands and adaptations of sympathy

Reformed Rakes did an episode on cheating in historical romance this summer, a plot that can inspire vitriol in readers. I’ve seen readers forgive the male character of a bodice ripper for his violence, but not his cheating and be furious as a female character for taking back a cheater. In the episode we argue that cheating makes for good plot, that a lot of books that people call cheating books aren’t actually cheating books, and that cheating isn’t even really a “trope” as much as a plot point because of the variety of beats the plot can take on.

We tried to land on what frustrates people so much about cheating in romance. It’s an act that can be hurtful, but it is one that is, on its face, non-violent and something clearly very human. I’m really proud of that episode, but since we recorded it, I’ve continued to think about infidelity in romance plots, particularly stories about wives who are unfaithful, since we found a dearth of this type of plot in historical romance. One such wife is Francesca da Rimini, made famous by her inclusion in the second circle of hell, the circle of the lustful, by Dante in The Inferno.

Francesca was a noble woman from Ravenna, notable for its mosaics and as Dante’s actual burial place.1 Francesca was married to Giovanni Malatesta, and one day while her husband was away, she and her brother-in-law Paolo were reading the story of Lancelot and Guinevere. Overcome by emotion while reading, the couple kissed and “read no more.” When the couple was discovered sometime later, Giovanni murdered them both. The historical record on the incident is scant. We only know a range of years the murder could have taken place: sometime between when Paolo leaves the army to return home and when Giovanni shows up in the record with another wife.

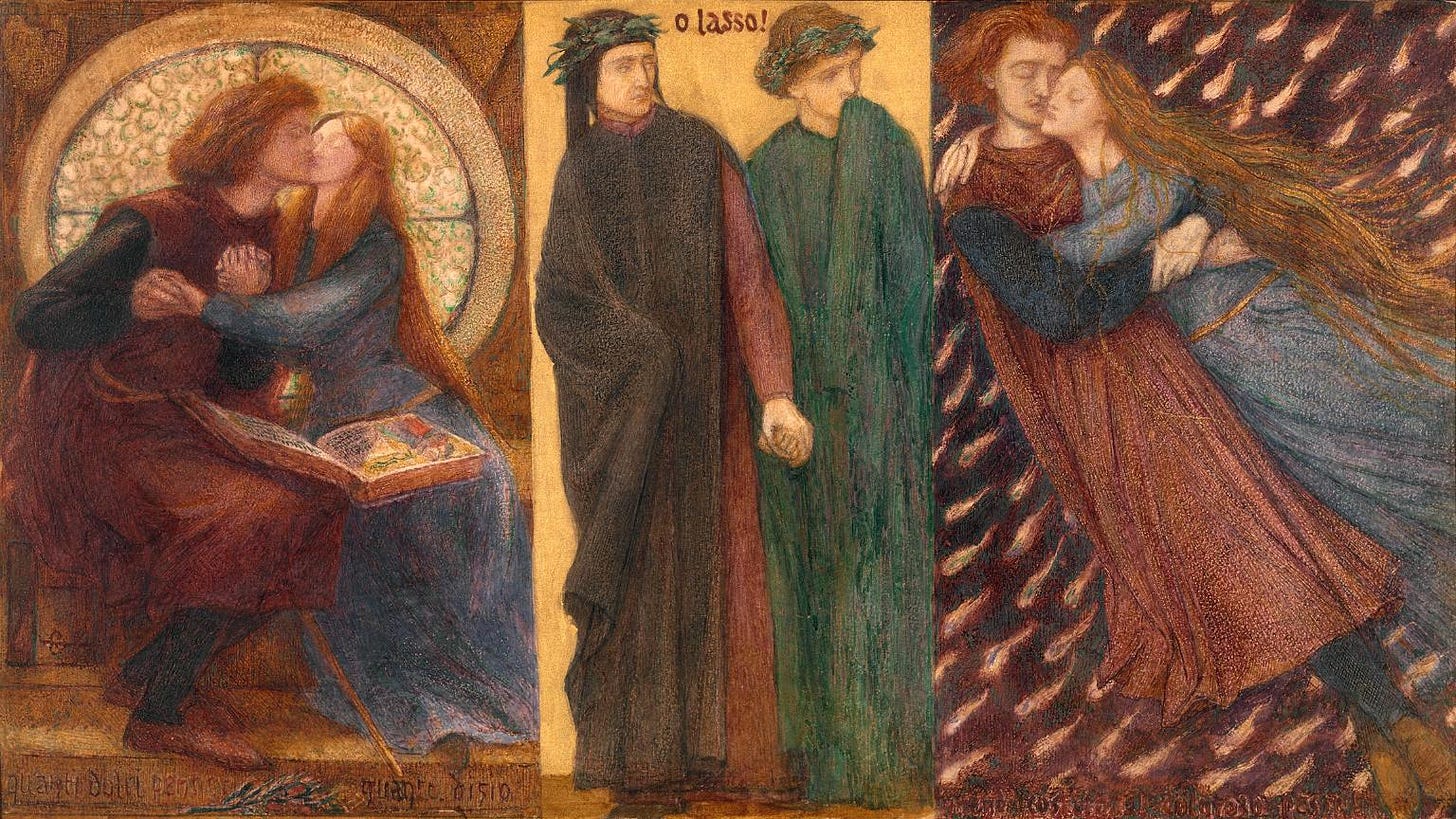

Generally in telling of this story, in all sorts of media, sympathies are assumed to lie unconditionally with Paolo and Francesca, despite the fact that we even know about them because of their infidelity. Is it because they are met with violence in real life? Or punishment in their narrative? So we can collectively say “oh what a tragedy (and they got what was coming to them)?” If we follow translations and adaptations of the story, we can trace the threaded needle between pity and sympathy in the 700 year history of this story.

Dante’s Francesca (in Italian and in English)

The story of Francesca and Paolo is incredibly bare in the Canto--Paolo isn’t even given a first name. Dante is able to recognize Francesca with little information, indicating some level of celebrity achieved by the tragic lovers in 12th-century Italy. But while the facts may be sparse, the subtleties of emotion and pity are not. It’s not a revelation or an original thought to say that Dante is able to do so much on this vector in a comparatively limited format.2

Dante first recognizes and expresses desire to speak with the couple almost exactly halfway through the Canto, after Virgil has explained the second circle to the poet. The second circle is for the lustful and their punishment is to be cast about by an unpredictable wind, reflective of their lack of reason for their decisions in life. Dante can only speak to Francesca and Paolo when the wind momentarily settles.

Francesca uses three of her speaking stanzas to thank Dante for visiting the sinners. Then after giving very little identifying information, referencing her hometown not even by name, but by its relationship to the river Po, Francesca begins the first part of her monologue, analytic rather than narrative, about the nature of tragic love and its sensory impact on the couple. These three stanzas are most famous for the anaphora of the first line in each stanza:

Love, that can quickly seize the gentle heart,

took hold of him because of the fair body

taken from me—how that was done still wounds me.

Love, that releases no beloved from loving,

took hold of me so strongly through his beauty

that, as you see, it has not left me yet.

Love led the two of us unto one death.

Caina waits for him who took our life.”

These words were borne across from them to us. (Inf. 5.100-108, Mandelbaum translation)

Then prompted by Dante to tell “with what and in what way did Love allow you/to recognize your still uncertain longings?” Francesca finally gets to the details of her love affair.

“One day, to pass the time away, we read of Lancelot—how love had overcome him. We were alone, and we suspected nothing.

And time and time again that reading led our eyes to meet, and made our faces pale, and yet one point alone defeated us.

When we had read how the desired smile was kissed by one who was so true a lover, this one, who never shall be parted from me,

while all his body trembled, kissed my mouth.

A Gallehault indeed, that book and he

who wrote it, too; that day we read no more.” (Inf. 5.127-138, Mandelbaum translation)Francesca speaks no more as well and Dante promptly faints, as he is wont to do.

It’s maybe the most iconic image from Dante’s Hell--the lovers being punished in the Second Circle, stirred up in a whirlwind, damned to be always reaching for each other, with no control of their forward movement. Possibly Brutus, Gaius and Judas in the mouths of Satan are more recognizable? But all three of those betrayers have non-Dante cultural footprints. Dante was the first chronicler of the tragic couple from Ravenna and knowledge of the affair comes from Dante, not a historical record. We know about Francesca and Paolo because Dante wrote about them and we care about them so much, in part, because of when Dante was translated into English for the first time.

Though referenced piecemeal in earlier periods of English literature, Dante’s Inferno was not comprehensively translated into English until 1805 by Reverend Henry Francis Cary and then that translation was praised by founder of the Romantic movement, Samuel Coleridge, nine years later. Peter Levine3 argues that this philosophical moment being the one that thrust Dante into the English consciousness created gaps between the poet’s stance on the story of Francesca and Paolo and the Romantics’ (and the rest of the 19th century’s) interpretation on Canto V. And this gap is central to the big critical questions for the Canto: how much sympathy does Dante, traveler, have for the couple? Is that level different for Dante, poet? How much pity is the reader supposed to have for the unfaithful, who, after all, are damned? Does pity for their damned state belie sympathy with their tragic love?

Despite Francesca and Paolo’s firm placement in hell by Dante, Cary, and then the poets inspired by his translation to write English poems or to conduct loose translation of their own, do seem to extend further sympathy to Francesca than literal interpretations of Dante’s Italian would suggest. Theologically, she, and Paolo, “should” have resisted the temptation because their adultery is a sin or at least repented, even at the last minute (there’s a whole section of sinners in Purgatory, with redemption potential, who died violently and never received the Last Rites, but repented in the last moments of their lives). Dante is characterized as being sympathetic to sinners all the time, but Levine argues the sympathy isn’t nearly as expansive or unconditional in the original Italian. The Romantics’ framing is different.

Take, for example, Dante’s infamous swoon at the end of the Canto, first related here by Leigh Hunt4 in his attempt at translating Canto V5 and then Levine’s more literal translation.

While thus one spoke the other spirit mourn'd

With wail so woful, that at his remorse

I felt as though I should have died.

I turn'd Stone-stiff; and to the ground, fell like a corse. (Leigh Hunt)While one soul told its story

The other wept, and I collapsed.

As if I'd died, I swooned from pity

And crumpled like a falling corpse. (Peter Levine)Francesca is the spirit speaking and Paolo is the one wailing/weeping. The remorse of Paolo is added by Leigh Hunt, as is the cause and effect of Dante’s swooning. In Hunt’s telling, it reads as though Dante is swooning from empathy, feeling Paolo’s remorse as his own. In the literal translation, it reads much closer to general Christian pity for the damned and Dante’s own typical faintness.

The translation of Dante that I have read most recently is from Ciaran Carson and he gives us this, preserving more of the terza rima of the original Italian, unites the cause and effect, with sympathy and pity.

And while one half of this fond pair so spoke,

The other wept so much I fainted. All

Of me was overwhelmed by that stroke

Of pity; and I fell, as a dead body falls. (Ciaran Carson)Renato Poggioli, whose close reading of the Italian I relied upon to struggle through the Italian verse, reconciles Dante’s pity and judgment by suggesting both must be present: “The ‘romance’ of Paolo and Francesca becomes in Dante’s hands an ‘antiromance,’ or rather, both things at once. As such, it is able to express and to judge romantic love at the same time.”6 In the notes of the Hollander translation, the translators suggest that Dante’s pity toward the lovers is supposed to be questioned by the reader. This qualification makes sense to me--after all, we’re only two circles into the Inferno and both Traveler and Poet Dante are fallible humans, who have and will sin again. If, only five cantos into the hundred canto project of the Divine Comedy, Dante already is able to overcome any alignment with sin, what is the point of his journey?

An implied lesson to the reader with Dante’s fall and the sudden remembrance of punishment also works in consideration with the circumstances of Paolo and Francesca’s affair--they were reading the romantic story of Lancelot and Guinevere just before they kissed. Francesca blames both the book and the author of the book for acting as their Gallehault, the intermediary between Lancelot and the Queen. The Italian version of the name “Galeotto” has since become slang for both an erotic book and a panderer. Boccaccio subtitled his Decameron “Prencipe Galeotto” or Prince Galehaut as a reference to the knight’s bringing of together the lovers.

Dante might have wanted to avoid that potential alignment between himself and the panderer knight, as author of a romance. Though Francesca’s reference ignores that had the couple only kept reading, they would have read how Lancelot and Guinevere’s affair leads to the downfall of Camelot. Dante makes sure to remind his reader of an inevitable fall much closer to the close of the romance.

The presence of Dante’s pathos and judgment doesn’t keep our Romantic poets from identifying with the lovers in sympathy. Byron, though he promised he meant to translate the Canto faithfully, wrote his “Francesca da Rimini” starting at the lover’s introduction and took liberties with the intensity of some of the descriptive words. Carol Rumens of the Guardian suggests that his version is more “masculine,” which I think is a little essentialist, but there are some extensions that make the images more violent. And, as Rumens points out, he translated the poem while he was conducting an affair with a married woman from Ravenna, possibly casting himself as Paolo.

John Keats wrote a sonnet in response to reading Canto V--adorably originally composed in his copy of Cary’s translation. Instead of retelling any part of the Francesca and Paolo story, the sonnet relates dreaming after reading the canto and the poet’s dream self being condemned to swirl about in the hurricane of punishment, along with the other sinners.

Probably the newest adaptation of the story is Hozier’s “Francesca” off of Unreal Unearth, his latest album that is explicitly based on Dante’s Inferno. In this song, Hozier takes on the first person persona of silent Paolo, assuring Francesca that the inevitable damnation was worth it for their love. From the Hozier’s “Behind the Song” video, it seems he read at least the Hollander translation of the poem, given the phrasing of the translated quotation “Love, which absolves no one beloved from loving,” that the singer cites.

But my entry point into thinking about Francesca da Rimini again in the past few weeks was Tchaikovsky and an adaptation with no words to fuss over.

Tchaikovsky’s Francesca (and not his Antonina)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wrote a tone poem based on the canto in 1876, first performed in 1877. A tone poem is a piece of orchestral music intended to represent the content of another work of art. Tchaikovsky’s score can be followed through Dante’s descent to the circle of the lustful, the tempestuous punishment meted out to the sinner in that circle, then the poet (represented by a single clarinet) asking Francesca specifically to tell her story, the romantic swells of Francesca’s narrative, the romance cut short by her and Paolo’s murder with violent brass, a requiem passage, and the theme of the hurricane of punishment starts up again. The whole thing is one movement about 25 minutes long. It’s great!

Tchaikovsky is far from the first or last composer to take up the story of these Italian lovers--the legacy of Francesca and Paolo may even be larger in orchestral music than it is in Romantic poetry or pre-Raphaelite art. Tchaikovsky wrote his version after reviewing a Liszt symphony that covers the whole of the Divine Comedy, though Liszt does include circle two of the lustful sinners as one of the locations he depicts. Rachmaninoff wrote a two-act opera of the story with libretto by Tchaikovsky’s brother (that Pytor previously rejected). And there are dozens of other operas and orchestral representations of the couple.

I think Tchaikovsky’s tone poem reflects the assessment that Dante’s original canto intends to elicit pity and then guiltily remind the listener of the truth of circumstances and the actions that led them there. After the frenetic passage leading to cymbals crashing that represents the murder of the couple, there’s the solemn and sudden requiem-like passage, which could feel like fitting end to a piece about the death of the lovers (this would be similar to Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet, composed a few years later, which has just a short final flourish of unified chords after the “death” passage), but the flurry of back and forth notes, representing the hurricane of punishment from earlier in the piece, starts back up again. The mourning requiem lasts maybe twenty seconds before being given over to a reminder of the setting for the tonal poem.

Tchaikovsky took up the stories of tragic women frequently in work, condemned for loving (see: his Romeo and Juliet fantasia, Swan Lake, many of his operas). Francesca da Rimini being written in 1876 and performed in 1877 means it was one of the last pieces met with public success before Tchaikovsky’s great crisis that shaped every decision, personal or creative that came after: his marriage to Antonina Miliukova.

Tchaikovsky, a gay man, had great anxiety about his relationships with men being the subject for gossip and in 1877, he decided he finally needed to marry to stave off rumors. Ever a believer in “fatum,” that when so close to when he decided to marry, he received a letter from Antonina, formal pupil at a music school where he taught, though not one of his students, Tchaikovsky took the coincidence as a sign of his salvation and destiny. The letter declared her love for him and then when the composer did not respond, Antonina sent a second letter threatening suicide. At the time, Tchaikovsky was working on his opera Eugene Onegin, featuring a heroine deeply in love with an indifferent dandy. Tchaikovsky’s sympathies, in his art, lay with the heroine over the dandy.

The composer agreed to meet the woman and on their second meeting, he proposed, to disastrous consequences. Antonina was in love with Tchaikovsky, but seemingly in a fixated, irrational way. She cared little about his music and expected the relationship to be romantic, despite his supposed explanation of his queerness and desire for a platonic marriage of convenience at the time of the proposal. After only six weeks, the married couple would be separated permanently, though Antonina would pine for her husband and tell various stories about why they were separated for years in ways that were more sympathetic to him than even his own recounting.

Tchaikovsky would threaten divorce over the course of their marriage, though Antonina would need to agree to sue based on his adultery. But even when Antonina had an illegitimate child, giving him grounds for his own suit, he would refuse to divorce, given his fears of exposure about his relationships with men. Tchaikovsky would speak cruelly about his increasingly unstable wife for the rest of his life and bemoan his financial duties to her. The now constant threat of exposure and increased financial strain would shape the last fifteen years of his life and career. The sympathy with tragic women in his work did not preclude Tchaikovsky taking part in a coupled tragedy of his own.

Tchaikovsky’s tone poem taking a neutral, if conflicted, stance about the condemnation of the lovers, allows the score to be transformed dramatically at least once in another medium. The dreams and fantasies of most of the adaptations that I am aware of primarily align the dreamer and listener/reader in sympathy with the lovers/cheaters, except for one, and it’s also the most fun one to me.

Sturges’ Francesca (and his Giovanni)

Unfaithfully Yours, dir. Preston Sturges (1948), starring Rex Harrison and Linda Darnell, is the last great film by Sturges, whose career was marked by disagreements with studios and struggles to get funding after burning bridges in Hollywood. The premise of the film is the husband half of a loving couple, Sir Albert, gets it into his head that his wife, Daphne, is carrying on an affair with his secretary, Tony. The husband is a conductor and happens to be conducting a program of three pieces, all of which focus on the follies of love: Semiramide by Rossini, about a female ruler of Assyria, who also happens to be placed in the second circle of Hell by Dante, who became wife to King Ninus only after her husband died by suicide out of shame for the King’s love of his wife, the overture to Tannhauser und der Sangerkrieg auf Wartburg by Wagner, about the redemptive power of rejecting sexual love as a motivator, and ending with Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini.

While he conducts all three pieces, the film follows Sir Albert’s daydreams and fantasies of confrontation of his wife about the affair, each colored by the spirit of the piece he is conducting at the moment. In the Francesca fantasy sequence, which is the final one, Sir Albert confronts Tony and Daphne directly and nests revelations about his other fantasies, telling them that he had first daydreamed about slitting Daphne’s throat and framing Tony during Semiramide, and then about being noble and forgiving the couple during Tannhauser.

Sir Albert assures them that neither of these fantasies will be made reality and instead the love triangle fate will be determined by fate, with a game of Russian Roulette, in a nod to Tchaikovsky’s country of origin. Tony refuses his turn and Sir Albert takes his own, shooting himself in the temple. The movie then returns to “reality” with Sir Albert conducting the final chords of the symphonic poem.7

The Francesca fantasy passage is maybe four minutes long, so obviously not the entire piece is represented in this scene. Instead what we get is the opening passage representing Dante’s descent as we zoom into Sir Albert’s eye and we stay there, until Sir Albert shoots himself and we transition to the final passages of the piece as we see him to return to reality and conducting his real orchestra. These elisions mean that something like 20 minutes, including the passages that reference the punishment of the couple, their love, and their murder, are excised from the total piece. There are visual references to the extended canto though, including a whirlpool around Sir Albert’s head after he has collapsed as we transition back to “reality,” recalling the hurricane of punishment and Dante’s “falling like a corpse.”

So who is Sir Albert in the extended metaphor of Francesca and Paolo? If this plot of this film is overlaid onto to the love triangle of the Malatestas, than Sir Albert is not Paolo, like Keats, Byron or Hozier, but Giovanni--the impotent (or at least made impotent by his jealousy) husband, who is moved to fantasies and realities of violence after his wife carries on an affair.

Sir Albert’s fantasies of punishment and consequence, his swooning, his creative impulse as a method of control and process could also align him more closely with the judgmental, if sympathetic and imperfect, Dante. Either way, Unfaithfully Yours turns the tragic romance of Francesca da Rimini on its head, following the Gothic villain of violent husband to his natural comedic consequences: being made a fool. The last third of the film is Sir Albert fruitlessly attempting his fantasies in sequence, with each of them failing to go off in increasingly absurd ways, only for his odd behavior to distress his wife so much that she unknowingly offers an explanation for her behavior that quells his marital anxieties.

Sir Albert may be our protagonist and our perspective, but as audience, we’re rooting for him to look foolish. The score of the last third of the picture is peppered with Looney Tunes sound effects when he falls through the caning on a chair, or pulling something off a shelf too hard, accidentally throwing it across the room. The threat of violence is replaced with the threat of embarrassment.

Unfaithfully Yours has risen in its critical estimation in the seventy five years since its release. In part, the release was marred by a real life, violent tragedy centered on Rex Harrison. A few months before the film was released, Carole Landis, Rex Harrison’s lover, died by suicide after he told he was leaving California to go to New York, interpreted as a breaking off of the affair and a refusal to leave his wife, Lili Palmer. He had had dinner with Landis the night before and then found her body the next day when he returned to her apartment. Harrison waited hours before calling the police and attended Landis’ funeral with his wife.

Harrison’s romantic life is marked by cruelty toward romantic partners that is often so specific to their personal tragedy.8 I think about Harrison’s real life cruelty quite a bit, in a part because he is in so many of my favorite movies that are dependent on a sexual, sinister, potentially violent, but also potentially comedic or romantic, persona to work. See: Over the Moon, Blithe Spirit, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, My Fair Lady and Unfaithfully Yours.

Dante has all that anxiety about being a Gallehault, a literary panderer, drawing clandestine lovers together to their downfall with romantic depictions of affairs separated from their consequences. But Unfaithfully Yours’s adaptation of Francesca’s story puts into focus, first in fiction and then in real life consequences surrounding the film, other warnings, one against buffoonery and looking like a chump, and another where Paolo abandons Francesca to violent consequences of the affair alone by aligning the viewer’s perspective, if not all together their sympathies, with the “victim” of the supposed infidelity.

In Unfaithfully Yours, Sir Albert references “the unwritten law” protecting him as he is proposing the Russian Roulette game. He is pontificating about his largesse, playing the fateful game. He sees this as an act of grace, not murdering Tony and Daphne outright, like Giovanni Malatesta did with his victims. Sir Albert thinks his threatened violence will be forgiven since he is in the right, though the last third of the film evolves into screwball, with him being punished by inanimate objects. Dante himself makes it clear that Giovanni Malatesta will not escape punishment, though he is still alive at the writing of the poem. Francesca says “Caina waits for him who took our life.” Caina is a section of ninth and lowest circle of hell, specifically for those who betray kin, named after the first murderer, Cain, who resides there.

The structure of hell is that the lower the circle, the worse the punishment and sin, so Giovanni will be condemned to a lower hell and worst fate than his Francesca and Paolo, even if some romance readers find cheating harder to forgive than murder.

Recommendation

If you’ve gotten this far and want a romance recommendation for books that deal with sin, God, infidelity and the threat of damnation read For My Lady’s Heart and its sequel, Shadowheart by Laura Kinsale. I picked up Shadowheart recently, independent of feelings about Francesca da Rimini and found it is a helpful companion.

There’s a false tomb for Florence’s favorite son in Santa Croce. The city has occasionally asked for the bones back in the seven hundred years since the poet’s death--Ravenna always refuses. Florence should have thought about that before they exiled him.

Dante writes in terza rima, terzinas in a descending rhyme scheme of ABA BCB CDC DED, continuing until the end of the canto. The three lines of the terzinas make a beginning, middle and end of each stanza. Also, Italian’s limited vowel endings of words compared to English and the way that Italian meter is measured means that in order to retain the form, Dante rarely has to vamp with meter markers of our favorite English pentameters (“And yet,” “So,” “Alas”). This form means his syllables are packed with meaning.

Peter Levine, “Keats against Dante: The Sonnet on Paolo and Francesca.” 51 Keats-Shelley Journal 76 (2002). JSTOR.

The fact that we can talk about Leigh Hunt doing anything, other than being the basis for Harold Skimpole in Bleak House is a real boon for Leigh Hunt.

Leigh Hunt both translated Canto V in his commentary on Italian poetry and wrote an original poem based on Francesca and Paolo, The Story of Rimini.

Renato Poggioli, “Tragedy or Romance? A Reading of the Paolo and Francesca Episode in Dante’s Inferno,” 72 PMLA 313 (1957).

For more analysis of the music in the film, see Martin Marks, “Screwball Fantasia: Classical Music in Unfaithfully Yours,” 34 19th-Century Music 237 (2011).

The other one that always gets me is his next affair partner, Kay Kendall. Still married to Palmer and having an affair with Kendall, Harrison learned from Kendall’s doctor that Kendall had leukemia. Harrison told Palmer and Palmer agreed to a divorce so that Harrison could publicly care for ailing Kendall. The acute cruelty is that Kendall was never told of her leukemia, by her doctor or by Harrison.

i love your continued writing on the tchaikovsky bio <3

Love the mention of Dante's poor constitution, he was falling over quite often. Also loved the Tchaikovsky rec, I don't listen to a ton of instrumental stuff but it was a fun accompaniment to reading this! And your concluding framing of Dante in opposition to hoards of romance reviewers did make me laugh. I find the willingness of readers to excuse violence over cheating super interesting in general, like the humiliation is what makes it unforgivable and not the degree of harm? And I did recently find both of these Kinsale books at a used bookstore and am excited to read them soon!