Giornata is my weekly media diary, a paid feature, coming out on Thursdays, covering whatever I read, watched, or listened to in the last week!

The Met Cloisters: At the Cloisters in New York, there are multiple signs that include lines from the poem, “The Cloisters” by Jorge Luis Borges. This is the whole thing (translated by W.S. Merwin) and I bolded the lines that I remember being on signs.

From a place in the kingdom of France

they brought the stained glass and the stones

to build on the island of Manhattan

these concave cloisters.

They are not apocryphal.

They are faithful monuments to a nostalgia.

An American voice tells us

to pay what we like,1

because this whole structure is an illusion,

and the money as it leaves our hand

will turn into old currency or smoke.

This abbey is more terrible

than the pyramid at Giza

or the labyrinth of Knossos

because it is also a dream.

We hear the whisper of the fountain

but that fountain is in the Patio of the Orange Trees

or the epic of Der Asra.

We hear clear Latin voices

but those voices echoed in Aquitaine

when Islam was just over the border.

We see in the tapestries

the resurrection and the death

of the doomed white unicorn

because the time of this place

does not obey order.

The laurels I touch will flower

when Leif Eriksson sights the sands of America.

I feel a touch of vertigo.

I am not used to eternity.

I had never been to the Cloisters, despite going to Manhattan probably twenty times in my life and once self-identifying as proto-Renaissance art history girl. The reconstructed Medieval monastery is at the very top of Manhattan and I’ve never felt like I had enough time to go all the way up and back and get in whatever other cultural musts I was packing into my weekend.

I wanted my first time to be a little later in the year, so more things would be blooming in the garden. But I had a half day and the motivation to visit this past Saturday, so I went when the bulb flowers were just starting to peek out of the ground.

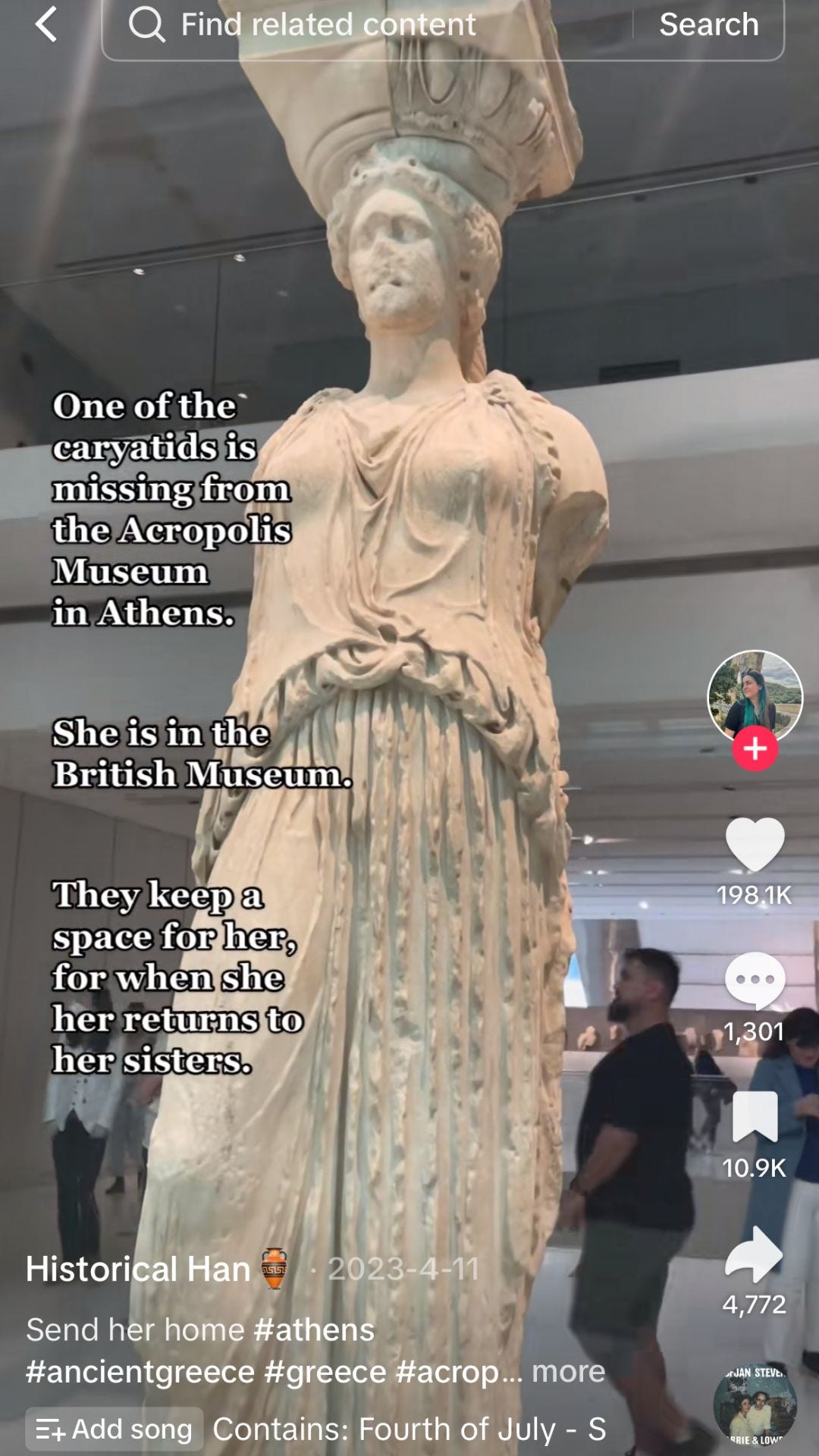

The idea of any art museum is already in tension with itself as a democratic, exclusionary, archival, authoritarian, money-laundering institution. Museums of objects once in situ exacerbate these contradictory compulsions in a visitor. See a screenshot below of the kind of breathless emotion I see a lot, specifically about the Caryatid2 at the British Museum, one of the pieces of the Elgin Marbles. Anyone can have an intuition about what belongs in a museum and where that museum should be and who should be able to access that museum. All of this is tied together by the fact that people who collects masses of things that go in museums are often off-putting weirdos with disdain for the public!3

The Cloisters are like that, but complicated again by the fact that so much of what you’re looking at is effectively detritus. The original architecture of the Cloisters from four French abbeys, the Cuxa, Saint-Guilhem, Bonnefont, and Trie cloisters, from the 9th to 16th centuries. The architectural elements had been purchased by George Grey Barnard, with the idea that eventually the Metropolitan Museum of Art would purchase the collection. They first turned down the idea, though the involvement of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. would eventually lead to the Met’s purchase of the collection (after Barnard had set up his own museum in north Manhattan) and the removal of the collection to land owned by Rockefeller in Washington Heights.

Barnard didn’t just deal in the architectural elements, but in objects and in stories. He romanticized his role as investigator and savior of Gothic and Romanesque flotsam and jetson, by “describ[ing] his treasure hunting in adventurous detail. He claimed that he had found his limestone relief of the Miracle of St. Hubert and the Stag embedded in the enclosure of a pigpen, and that the magnificent thirteenth-century tomb figure of Jean d'Alluye was being used, face downward, as a bridge over a stream. He pictured himself a roving and romantic figure, bicycling across French fields and spotting Gothic masterworks in the mire.”4

The removal of the stones from France was not without drama, with the French government developing an interest in the stones staying its country basically parallel to Barnard preparing to take out the materials. But all four cloisters had been abandoned or partially destroyed already, with the shrinking of monastic culture, the Revolution’s interest in ridding the country of religious iconography, and just a general disinterest in preservation. These were the parts of monasteries that lasted, but were crumbling in disuse before Barnard’s interest. Whether that changes the justification for the move or not is up in the air for me, but it does substantially change the experience of the museum.

Because Borges is right, the Cloisters is a weird experience because it’s a museum (announced artifice of setting) and simulacrum (hidden artifice of setting). Time cannot obey an order when you’re looking at things from Florence and France and Germany out of context and in conversation, while the walls around you are pretending to be a context. This sounds like I’m being down on the concept of the Cloisters—I had a great, singular time! The only experience that I’ve had in the world that comes close is visiting the Colosseum in Rome, which, famously, sneaks up on you as you’re walking toward in because it is such an iconic image, but it is also just kind of suddenly there. The Unicorn Tapestries made me cry. And I thought about the animated television show Gargoyles, which also features a medieval building being moved to New York.

Moby-Dick, by Jake Heggie at the Met Opera: I was going to say “they’re letting guys named Jake write operas now,” but Puccini’s first name was Giacomo. So Jakes have been writing operas for awhile. But I went to the opera with

! And it was wonderful! I read Moby-Dick in 2018, but saw a production at the Alliance Theater in Atlanta that originated at the Lookingglass Theater in Chicago in 2016, so I was interested in this opera as another iteration of stage adaptation of a book that seems so unwieldy and winding. The main thing I remember about the Lookingglass Theater’s adaptation was the aerial silks and acrobatics (and at one point, when the men start drowning during the final whale attack, players pull silks over the audience, like the parachute game from elementary school gym class).What I’ll remember most about this opera is also the staging and blocking—the amount of storytelling that happened with ropes and wires across the stage, visually apart of a diegetic ship, but also helping the clarity of story was great. I really enjoyed this interview with Jake Heggie at the Paris Review about his process in writing the work. There are shows through the end of March, so highly recommend if you are in New York! I’m hoping/imagining there’ll be a Met OnDemand5 recording of the opera at some point too.

My favorite quotation from Moby-Dick is in the Cetology chapter, where Ishmael is listing all the whales.

But I now leave my cetological System standing thus unfinished, even as the great Cathedral of Cologne was left, with the crane still standing upon the top of the uncompleted tower. For small erections may be finished by their first architects; grand ones, true ones, ever leave the copestone to posterity. God keep me from ever completing anything. This whole book is but a draught—nay, but the draught of a draught. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience!

It always makes me think my favorite part from F for Fake (dir. Orson Welles), the Chartres Cathedral speech, which captures one of the appeals of Medieval art to the American public in the first half of the 20th century, connecting us back to the Cloisters. When the architecture was being moved to New York, the sentiment of the Artist as Author, Individual and Brand was growing with the rise of Modernism, so a deep interest in the collaboration and anonymity of medieval art makes sense as a reaction, especially when it was made in service of a higher power.

Nell Mescal’s first American show: I think Mescal is suffering from the nepo sibling negative factor, where people assume you don’t have the juice because your brother has been nominated for an Oscar. When, in fact, she is the sibling with the most juice! She also has a problem that a lot of her peer share as bedroom pop, whisper singers—many of her recorded songs sound nearly identical.6 I already liked her songwriting and voice, but her live performances and those arrangements were much more varied than her first two EPs. I’d love for her to get a smart producer and be an opener for literally anyone other than Gracie Abrams.

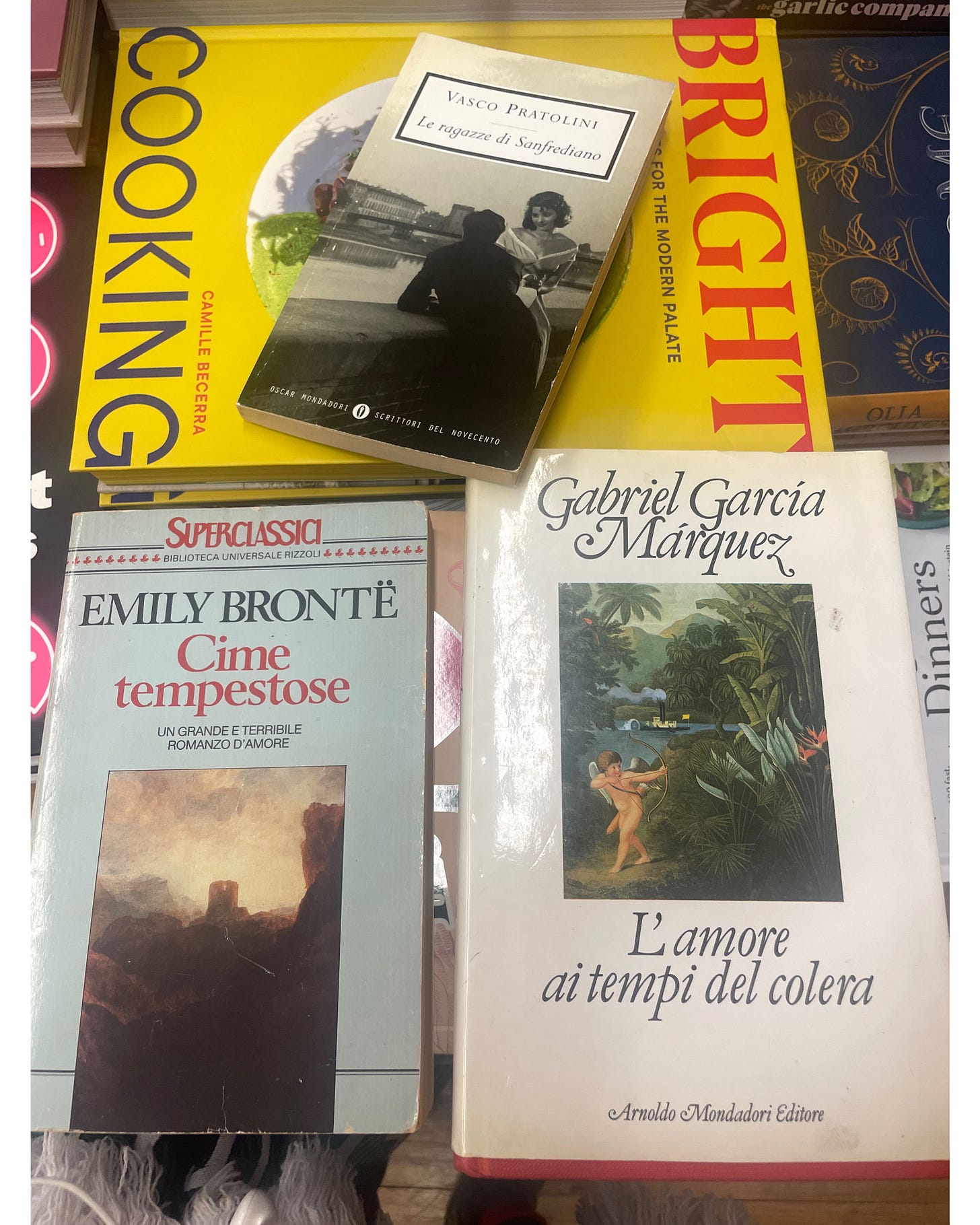

Italian book haul: One of my goals when I was in New York was to try and get a physical copy of Lessico famigliare by Natalia Ginzburg, which I’ve been reading in Italian on archive.org. The two bookstores (Rizzoli and The Strand) I went to with promised Italian language sections did not have it in Italian, but I did pick up some books: Dante by Alessandro Barbero and Le ragazze di Sanfrediano by Vasco Pratolini, both originally in Italian and then a copy of Wuthering Heights (Cime tempestose) by Emily Bronte and Love in the Time of Cholera (L’amore ai tempi di colera) by Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Love in the Time of Cholera is probably the most exciting find, as a book originally written in Spanish that I have read in English in my target language. I’ve never taken a Spanish language class, but Italian and Spanish are nearly as mutually intelligible as Italian and French (my high school language). I think reading this in Italian, occasionally alongside a Spanish ebook edition for comparison will be fun.

Here’s the famous first sentence in all three languages:

Spanish: Era inevitable: el olor de las almendras amargas le recordaba siempre el destino de los amores contrariados.

English: It was inevitable: the scent of bitter almonds always reminded him of the fate of unrequited love.

Italian: Era inevitabile: l’odore delle mandorle amare gli ricordava sempre il destino delgi amori constrastati.

Most important to me, person of the Italian 104 experience, in this sentence is seeing the imperfect form in practice. The habitual action of remembering unrequited love while smelling almonds! I’m hoping to supplement my Italian language classes with a translation class in the fall, so poking at these books that I’ve read before in English, translated into Italian will be a fun project. I almost bought a book of translated into Italian 20th century American poems, but it was too big for my bag.

Only true for people with New York addresses now. Claudia Kincaid will haunt your every step, Met Board of Directors.

The way people talk about the Caryatid is so obviously gendered in a way that I bristle at easily. The emotions about this specific piece over other feels anthropomorphic and possessive, surely in part because it is a statue of a woman

Thinking of my two favorite museums in the world: The Barnes Foundation and the Sir John Soanes’ Museums.

Tomkins, Calvin. “The Cloisters ... The Cloisters ... The Cloisters ...” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 28, no. 7, 1970, pp. 308–20. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3258513. Accessed 18 Mar. 2025.

I pay for this streaming service about once a month every year and watch a handful of operas. I do recommend it!

In an opening act, only has an EP out way.