Please check out the Gaza Evacuation Fund Book Auction. I’m so proud to know some of the organizers of this amazing effort to link book communities with fundraisers for Palestinians trying to leave Gaza. All the lots are incredible, but you can also directly donate to the GoFundMes listed here.

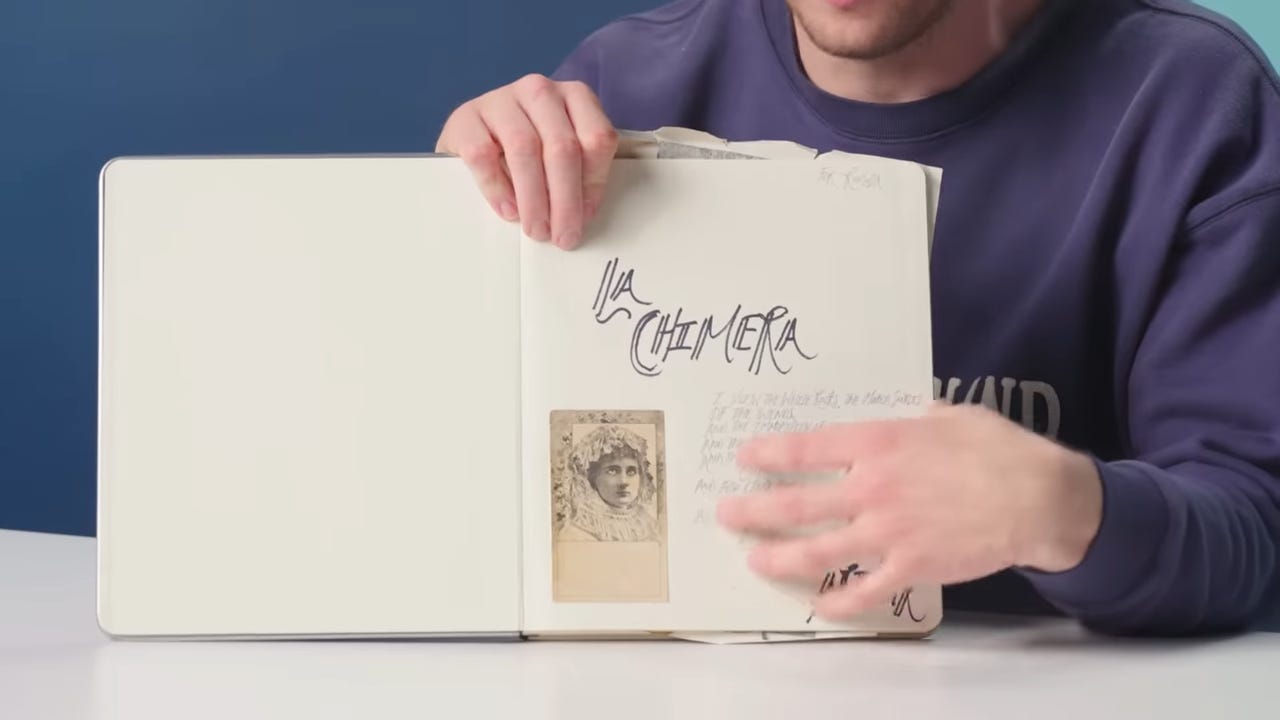

Reformed Rakes has a new episode out about For the Earl’s Pleasure by Anne Mallory, a paranormal romance between a woman and her long time social enemy, who is now a ghost. I love a ghostmance and what will probably be my most romantic movie of the year is an Italian ghostmance. Struggle through some Italian poetry with me and go see La Chimera.

la campana: the bell

In one scene in La Chimera (dir. Alice Rohrwacher, 2023), Arthur (Josh O’Connor) hands Italia (Carol Durate) a little antique brass bell, a children’s toy like a rattle. Italia asks what the item is and Arthur shrugs. Once she can hold it and shake it, she alights with recognition and announces “campanello!” (little bell) and teaches him the word. Italia has been teaching Arthur Italian throughout the film, accompanied by sign language to match, their own shared silent communication.

My knowledge of Italian is highly situational. My main aim for any of my Italian studies is to be able to read poetry and books that I want to in Italian and to talk about art and art history. And maybe get into a Katharine Hepburn in Summertime situation the next time I’m abroad.

But I can follow Italian conversations in movies okay (I can listen to the Italian in The Godfather, rather than read the subtitles, just to give you a baseline). In the film, Arthur’s Italian is much more fluid than mine, though he makes little pronunciation and agreement mistakes. But I’m pretty sure he should know the word for “bell.” I’m definitely sure it is one of the first nouns I learned, through just reading about Italian life and culture in art history classes. And he’s an archaeologist! Bells are very important to Italy! Particularly “campanas,” the word used for large church bells, which begets words like “campanello” “campanile” (bell tower), “campanaccio” (cow bell), and my favorite derivative “campanilismo” (pride in one’s hometown, think bell tower + machismo).

After I left seeing La Chimera the first time, I googled “La Chimera rohrwacher campana” and “La Chimera rohrwacher campanello,” looking for a possible explanation as to why this character, who speaks Italian for 95% of the movie didn’t know this word. I felt like in a script with so many layers of meaning, if Arthur was flubbing or forgetting a word, I thought there had to be a joke at his expense or some symbolic reason. Earlier in the film, he mispronounces the word for eyes: gli occhi. Within the text of the film, it is easier to clock why Arthur, who is searching for buried treasure, in the form of artifacts and a lost love, would get something wrong about eyes. He’s searching, looking and failing, and he is frequently looking especially at faces. But why miss campana/campanello?

What I turned up was Alice Rohrwacher talking about one source of La Chimera’s story and emotional aesthetic, Italian poet Dino Campana’s single volume of poems, Canti Orfici (Orphic Songs), published in 1914.

Rohrwacher says in an interview with Filmmaker Magazine: “The Canti Orfici1 are in some way the poems of Arthur. As I said earlier, Arthur is different from everyone around him. He belongs to another time, another era…Josh and I read over and over one of Dino Campana’s poems called “Chimera,” which depicts very well how Arthur moves about in moonlight, searching for this shape for this woman who may possibly be just a chimera.”2

Rohrwacher’s strong identification of Arthur with Campana’s poem, titled La Chimera, makes me think this must be a part of the joke—Arthur not seeing himself, not grasping his poet alter ego fully, but instead having to be identified and named, diminutively, by the character Italia, herself named after his adopted country.

Campana was an Italian poet from Marradi, which every introductory biography I’ve read mentions is technically in Tuscany, but is closer to the city Faenza, in Emilia-Romagna. It feels like the explanation of this at the beginning of any tracing Campana’s life is a neat shorthand for “he’s stuck between things,” “he’s a wanderer without a true region,” “he’s technically Tuscan, but always going to be a literary outsider.” And all of these things are true. Campana suffered from mental illness that made pursuing higher education difficult, as well as put strains on his relationship with his parents. He traveled widely, sometimes self-directed, sometimes under the coercion of his parents, and sometimes to stay ahead of the law. He was frequently arrested and incarcerated for “madness” during these trips. He would spend the last 14 years of his life in a mental institution outside of Florence, before dying in 1932 of sepsis.

He wrote the Canti Orfici, his singular book, between 1906 and 1913. He first sought publication with a highly respected Florentine publisher, but during a move, the publisher lost Campana’s only manuscript copy. Campana bitterly recreated his work in 1914 and published it with a printer in Marradi. The poems have a Futurist and Imagist bent, though Campana was distinctly not a part of either of these groups, more likely to look backwards for his references and inspirations (and unlikely to be totally accepted by any en vogue, formal aesthetic). I’m biased in favor of seeing Dante everywhere, and the structure, if there is one to the Orphic Songs, is a dreamy journey through the middle of Italy. It feels like a descent and a climb. Time slips and slides, with Campana jumping into and out of a dream setting, with few direct cues to the reader that time has shifted or slowed.

In the introduction to the Campana section in Twentieth Century Italian Poetry: An Anthology, Luigi Bonaffini writes that this “suspension of time, which is the final aim of this journey, can only be the result of a redemptive memory, which transforms private occasions into mythical epiphanies, and aims at the abolition of chronological time through the recovery of an inner dimension which is beyond time and history.”

la chimera: the mere wild fancy

In La Chimera, Arthur’s all out of sorts. He’s displaced, spatially, the classic non-Italian in Italy (Goethe, Will Ladislaw, George Emerson, Merton Densher),3 but he is also on the wrong temporal plane. The film starts with him dreaming of a woman and waking up on a train, returning from a stint in prison, punishment for his grave robbing activities. His friends have carried on without him, moving his pilfered artifacts from his ramshackle lean-to to prevent detection. But Arthur rages against things not being left as he left them, with the confrontation shown in silent movie mode, with a high frame rate. Time kept going while he was prison and time has kept going after he has lost Beniamina, his fiancé. In the film, Beniamina is only seen in 16mm shots, giving a sense that she is not real, or in Arthur’s mind, or removed from where we are. She is in a wooded area when we see her, pulling a string from that her dress that has gotten caught in the ground. She’s missing and the more we see her, the clearer it is that she is gone.

The mother of his lost fiancé, Flora, played by Isabella Rossellini, lives in a decrepit old manor, with grotesques painted on the peeling plaster walls. She is all too happy to stay exactly put in a tomb of a house, waiting for her lost daughter to return. The mother is how Arthur meets Italia, since she is working for Flora, basically as a housekeeper. Italia is awkward, but compelling and insistent at making a connection with Arthur, which he slowly accepts. She seems like a chance to walk forward.

Arthur works as a tombarolo (a grave robber) because of his training in archaeology but also because of the gift of his “chimeras,” which are fugue states he enters while auguring for the graves, suggesting a great pull between his 1980s body and the over two thousand year old tombs he intends to rob. I tombaroli specifically rob Etruscan graves, the pre-Roman people that lived in central Italy, primarily to the West, so including Tuscany, from the 10th century BC until they were integrated into the Roman Empire in 27 BC. Italy is a country with a long history and identity, both that have been simultaneously continual and broken. The Etruscans are on the very edge of the furthest back you can go. Even in a country where the Roman Forum is just *there* for cats to wander around in, the Etruscans have secrets exclusive to their times. But like anything in Italy, Etruria is not completely buried, with Arthur seeing mirages, reflections (or even earthly return) of his artifacts and their owners all around him. But that slippage of planes happens and the question is, is Arthur projecting into the limited Now or is he seeing Campana’s eternal moment, where everything that has ever happened, is happening at once?

The speaker of “La Chimera” addresses a woman in the second person, like an ode, but she isn’t just idealized, she is phantom. The poem opens describing ambiguities about the speaker’s perception of her. My favorite binary is when he wonders if she is an ivory figurine or another iteration of the Mona Lisa. The visible quality he emphasizes the most is her pallor: she is wan, she is pale, she is blood drained. She is dead? Still our poet keeps watch, outward: to the nighttime sky and the hills marked by labor and he calls her La Chimera.

Arthur’s fixation in La Chimera is looking back as far and deep as possible, but just as he is looking back to the edge of history when he handles the Etruscan artifacts, he is on the edge of time pushing the other way too. No one has lived past where he is living (which is true of any us at any present moment.) And the Italy of Arthur’s forward movement is juxtaposed with his tomb-hunting. There are smokey factories and lakes poisoned by chemical byproduct water, right next to some of the tombs where Arthur and his cohort find the oldest and most miraculous things. Arthur is reaching back to the extreme, but the now surrounds him as much as the past.

“La Chimera,” from Canti Orifici by Dino Campana

Non so se tra roccie il tuo pallido Viso m’apprave, o sorriso Di lontananze ignote Fosti la china eburnea Fronte fulgente o giovine suora de la Gioconda O delle primavere spente, per i tuoi mitici pallori O Regina O Regina adolescente Ma per il tuo ignote poema Di voluttà e di dolore Musica fanciulla esangue Segnato di linea de sangue Nel cerchio della labbra sinuose Regina de la melodia: Ma per il vergine capo Reclino, io poeta notturno Vegliai le stelle vivide nei pelaghi del cielo Io per il tuo dolce mistero. Io per il tuo divenir taciturno. Non so se la fiamma pallida Fu dei capelli il vivente Segno del suo pallore, Non so se fu un dolce vapore, Dolce sul mio dolore, Guardo le bianche rocce le mute fonti dei venti E l'immobilità dei firmamenti E i gonfii rivi che vanno piangenti E l’ombre del lavoro umano curve la sui poggi algenti E ancora per teneri cieli lontane chiare ombre correnti E ancora ti chiamo ti chiamo Chimera

Attempted prose translation by me: I do not know if your pale face appeared to me amongst the rocks or you were the smile of unknown distances. Your forehead gleaming ivory or the young sister of the Mona Lisa. O faded springs of your mythical paleness, O Queen, O young Queen. But for your unknown poem of sensual pleasure and sadness, wan, musical girl, marked by a line of blood, surrounded by your sinuous lips. Queen of the song, but for your reclining virgin head, I the nighttime poet kept watch on the vivid stars in the seas of the sky, for your sweet mystery, for your taciturn turns. I do not know if the pale flame of your hair was the living sign of your pallor, I do not know if it was a sweet vapor sweet around my pain, smile of the nocturnal face. I look to the white rocks, the quiet source of the winds, and the immobility of the firmaments, and the swollen rivers that go crying, and the shadow of men’s work curving on the high hills, and still for tender distant skies clear shadows run, and still I call you I call you Chimera

l’anima: the soul

The almost incidental old/new aspect of La Chimera reminded me so much of a favorite Italian film from 2021, Il Buco by Michaelangelo Frammertino. Il Buco translates to “The Hole” and most of the movie is a meditative recreation of the 1961 exploration of Abisso del Bifurto, a nearly 700 meters deep cave in Southern Italy, one of the deepest points in the country. There is next to no dialogue, any speech is overheard. As the explorers go downward, a Calabrian shepherd tends his flock.

There is an early scene showing the construction of Pirelli Tower in Milan. The scene is significantly less striking than any of the shots of the cave. But it is the thing I remember best about the film. The images of Pirelli Tower are certainly presented through a filter and are less awe-inspiring that the filming of the cave, despite the height of the building—the building appears in a television documentary, watched by the community in Calabria on a television in a bar. The shot starts out showing the frame of the television, but quickly cuts in, so the documentary footage of the at-the-time tallest building in Italy is fully integrated into the film. The title card comes immediately after and then we stay with our explorers and our landscape.

Milan is in the rich, urbane north of Italy and Pollino, where the caves are, is in much more rural south. The Pirelli Tower is the post-war resurrection, reaching, stretching upward and the Abisso is Italy before Italians, before Etruscans, before people, pitching into the earth. But in La Chimera’s 1980s Tuscany (central Italy), not even a juxtaposition of a film cut needs to happen to have the oldest thing and the newest next to each other.4

I titled this essay “my favorite Italian word.” It is, in fact, not “campana.” It is “anima.” With a Latin root that finds its way into English in animal, animus, animation, magnanimous, unanimous, the word means “soul,” “spirit,” the inside thing that makes something happen. In La Chimera, this is the word that the characters use to describe who is being stolen from when i tombaroli enter a tomb.

Anima became my favorite Italian word when I picked my favorite Petrarch sonnet, 204 of the Canzoniere.

Anima, che diverse cose tantevedi, odi et leggi et parli et scrivi et pensi; occhi miei vaghi, et tu, fra li altri sensi, che scorgi al cor l’alte parole sante: per quanto non vorreste o poscia od ante esser giunti al camin che sí mal tiensi, per non trovarvi i duo bei lumi accensi, né l’orme impresse de l’amate piante? Or con sí chiara luce, et con tai segni, errar non dêsi in quel breve viaggio, che ne pò far d’etterno albergo degni. Sfòrzati al cielo, o mio stancho coraggio, per la nebbia entro de’ suoi dolci sdegni, seguendo i passi honesti e ’l divo raggio.

Translation by AS Kline

Spirit that sees, hears, reads, speaks, writes, and thinks, so many diverse things: my eyes of longing, and you, among the senses that guide sacred noble words to the heart: how much later, or earlier, do you wish you had taken the road, that's so hard to follow, so as not to have met those two bright eyes or the steps of those beloved feet? Now with such clear light, and so many signs, there should be no error on this brief way, that makes us worthy of an eternal home. Strive towards heaven, O my weary heart, through the mist of her sweet disdain, following true footsteps and divine light.

I could probably connect most of Petrarch’s sonnets to La Chimera and Canti Orfici. The font of standardized Italian language is a man who grasping for and looking at a fragmentary, distant woman. But a soul making and regretting a decision, and then the volta of following some divinity anyway? That’s La Chimera!

In 1914, when Canti Orfici was still a bundle of potential, and Campana still had the chance to be embraced and nurtured by the Florentine literati, instead of rejected, criminalized and displaced, he wrote a letter to Giuseppe Prezzolini, an Italian literary critic, sending it along with a copy of “La Chimera.” In that letter he wrote: “Scelgo per inviarle la più vecchia la più ingenua delle mie poesie, vecchia di immagini, ancora involuta di forme: ma Lei vi sentirà l’anima che si libera.” (I have chosen the oldest the most ingenuous of my poems to send you, still old in images, still formally involute: but in it you will feel the soul freeing itself.5)

recommendations

The English Patient (dir. Anthony Minghella, 1996): I have no ability to be cynical about The English Patient. The trailer for it played on my VHS of Emma (1996), my most watched movie as a kid and I was kind of obsessed with the trailer, with all its Miramax Oscar bait glow, and the dramatic voice over. I loved the trailer so much, I put off seeing the movie for years, thinking “that’s for grown-ups.” I just love it and La Chimera made me think of it a lot.

Truly, Madly, Deeply (dir. Anthony Minghella, 1990): A BBC production starring Juliet Stevenson and Alan Rickman about a woman who has lost her partner, though he remains, haunting her flat. It’s very special and very underseen!

I haven’t actually read that many romances set in Italy (Shadowheart by Laura Kinsale is great), so I’ll just recommend what I always recommend: Chapter II of A Room with a View and Chapter XIX of Middlemarch.

I spent most of April reading romances set in or immediately after Waterloo and am just having a great time with that. My favorite so far has been The Lady’s Companion by Carla Kelly—I’m on a category romance kick!

The Orpheus references abound in La Chimera, doubling down on the basic structure of a man digging to find his lost love. The soundtrack has multiple references to L’Orfeo by Monteverdi.

I think of the word “chimera” meaning a hybrid animal, but the poems and the film use it more figuratively: an imagination, a dream, a figment or a power.

“I then rewrote the script imagining a man perhaps inspired by the young romantics in the 19th century who would come to Italy because they were passionate about the ruins, the so-called grand tour.” Alice Rohrwacher in Vogue

Also from the Filmmaker interview (I could just read Rohrwacher talk about this movie for days)

Filmmaker: Your films often look to the past, but not necessarily in a nostalgic way. How would you describe your connection to the past?

Rohrwacher: It’s hard to answer because I don’t have a specific theory on this. I don’t believe I’m a nostalgic person, but I am an attentive person—and when you pay attention to things, that’s about a disposition of the soul. Attention is a disposition of the soul towards the past and also the future. I believe that the most important thing that one can learn from the past is considering it not just as a combination of things that we still need to do, but also about the things that we leave behind us when we’re no longer there. When you think about the future, it’s good to have a certain softness towards the archeologists of the future, who hopefully will not just find toxic waste, plastic, weapons and bombs, but something beautiful that we’ve built and purposely left behind. So, in terms of thinking about the past, that’s what I think about. I think about something that can remind me that I will be the past myself at some point. And this isn’t a bad thing. It’s something that gives me a certain degree of happiness.

“Introduction,” Orphic Songs, Dino Campana, trans. Luigi Bonaffini

This is so great; wonderful and necessary reading on both these films!!

I hope you don't grow weary of my film recs but would also suggest you peep Martin Eden and Transit - one Italian, one German/French film - both of which play with time in similar/dissimilar ways, where it appears to be past and present at the exact same time. Martin Eden is sort of like, the aggressively communist version of La Chimera in some ways (Jack London adaptation) with a hot guy who is not the type of hot guy that Josh O'Connor is but worth discussing nonetheless.