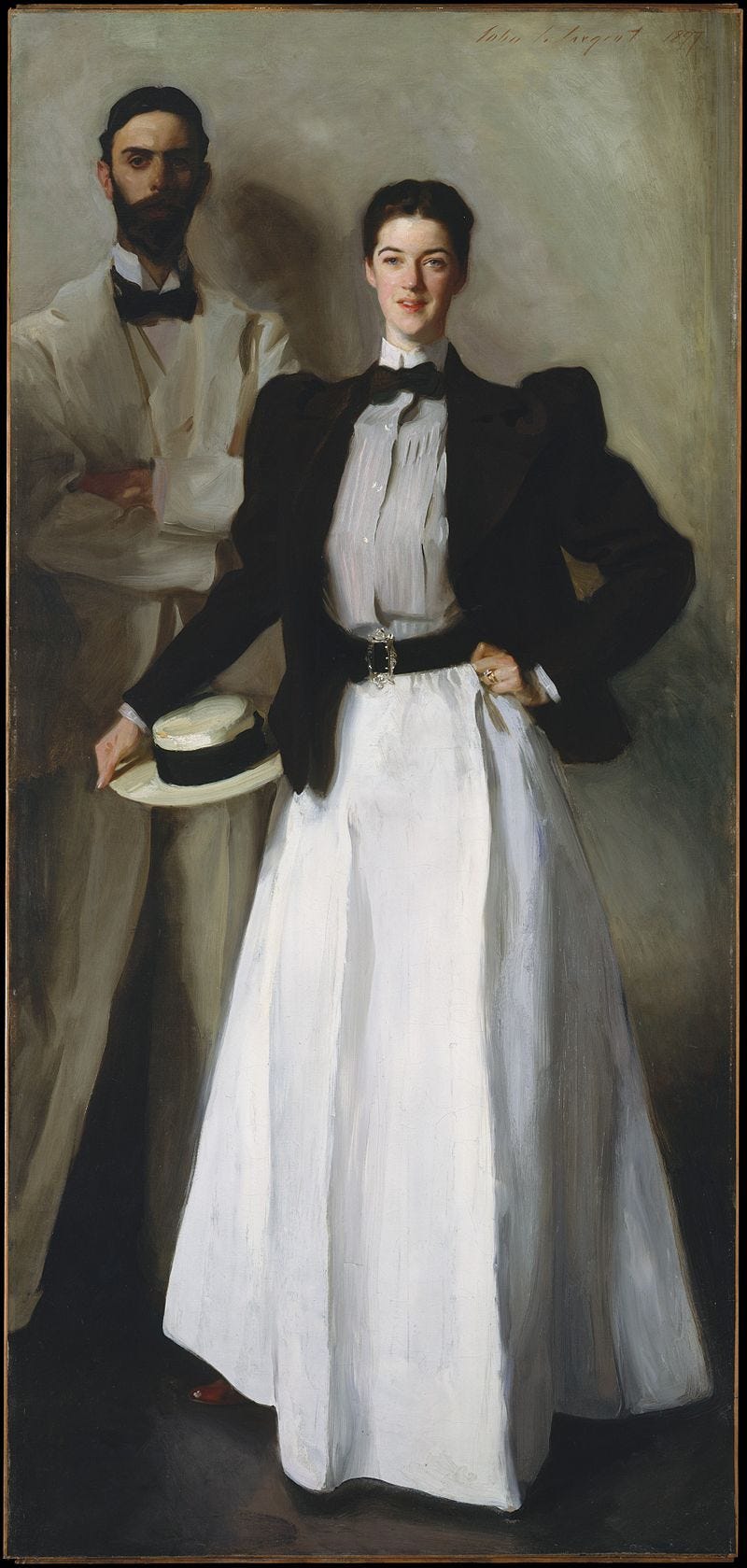

non-romance, romance, #10: Mr. and Mrs. I.N. Phelps Stokes, John Singer Sargent

seeking: great dane husband

A new non-romance, romance! This is a monthly series where I write about something that is not a genre fiction romance novel through the lens of romance. This month is about one of my favorite paintings and the romantic and art historical context of its execution.

Let me know if you’ve heard this one before.

A pair of newlyweds, a beautiful heiress and an up-and-coming architect, have secured a boon. The painter of all painters, of Florence, then Paris, and now London, is going to paint the wife. The couple is wealthy, but a family friend has paid the fee for the portrait as a wedding gift, though the couple did fund their two-year honeymoon, mostly in Paris, from New York which has led to this mini (months-long) detour in London.

The painter is known for his paintings of women in dresses. Big, silk chiffon, House of Worth creations. The husband and wife and painter settle on a blue one, to match her eyes, and the work begins. And goes on and on for five weeks. The husband sits by, though he is not needed. He mostly just wants to be close to his new wife. The wife is posed with a fan, that she is instructed to tap repeatedly on a table so that that gesture might be captured. Suddenly during one of the sittings, the husband and wife watch the painter undo all his work, scraping the oil paint off the canvas, dissatisfied with this woman, in this dress, in that pose, on this canvas.

Other confection dresses are proffered as options by the wife at the next sitting, but after considering them, the painter says no, she will wear the outfit that she wore when she walked into the studio, a walking dress. She will appear just as she is at that moment, wind-swept and alive, coming inside after a walk.

Ever fond of referencing the compositions of portrait masters, the painter now intends to procure a Great Dane to stand beside the wife, referencing a Van Dyck (shown below) and emphasizing the monumental size of the canvas: seven feet tall. A great dog for a grand painting.

But the intended dog never appears. The friend who had the required dog has left London. Nevertheless, another substitution is made. First, there was a day dress for a ball gown and now it’s the husband for the dog. The portrait is now a double. A wedding gift has become a marriage portrait.

The Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. I.N. Phelps Stokes (1897, John Singer Sargent) was originally meant to just be a portrait of Edith Minturn Stokes, until her husband, who was sweetly attending all of his wife’s sittings with Sargent, volunteered to take the absent dog’s place. Despite its title, the painting remains, somehow, mostly a painting of Edith. The shallow field of painting, which combined with the large scale of the canvas makes it feel like she is looming over you, possibly standing up against a window, only provides two real levels of depth: the plane where Edith stands and the plane where Isaac stands, behind her in every way.

Sargent’s portraiture and artistic career somehow exist on both the radical edges and the accepted middle. His history, the child of Boston Brahmin expats, born in Florence, Italy, driven out of Paris over the scandalous Portrait of Madame X, meant he was both pedigreed and exciting enough for the nouveau riche of the Gilded Age of New York to chat about constantly. He was able to gain the admiration of some English patrons, but he was an obsession for East Coast Americans.

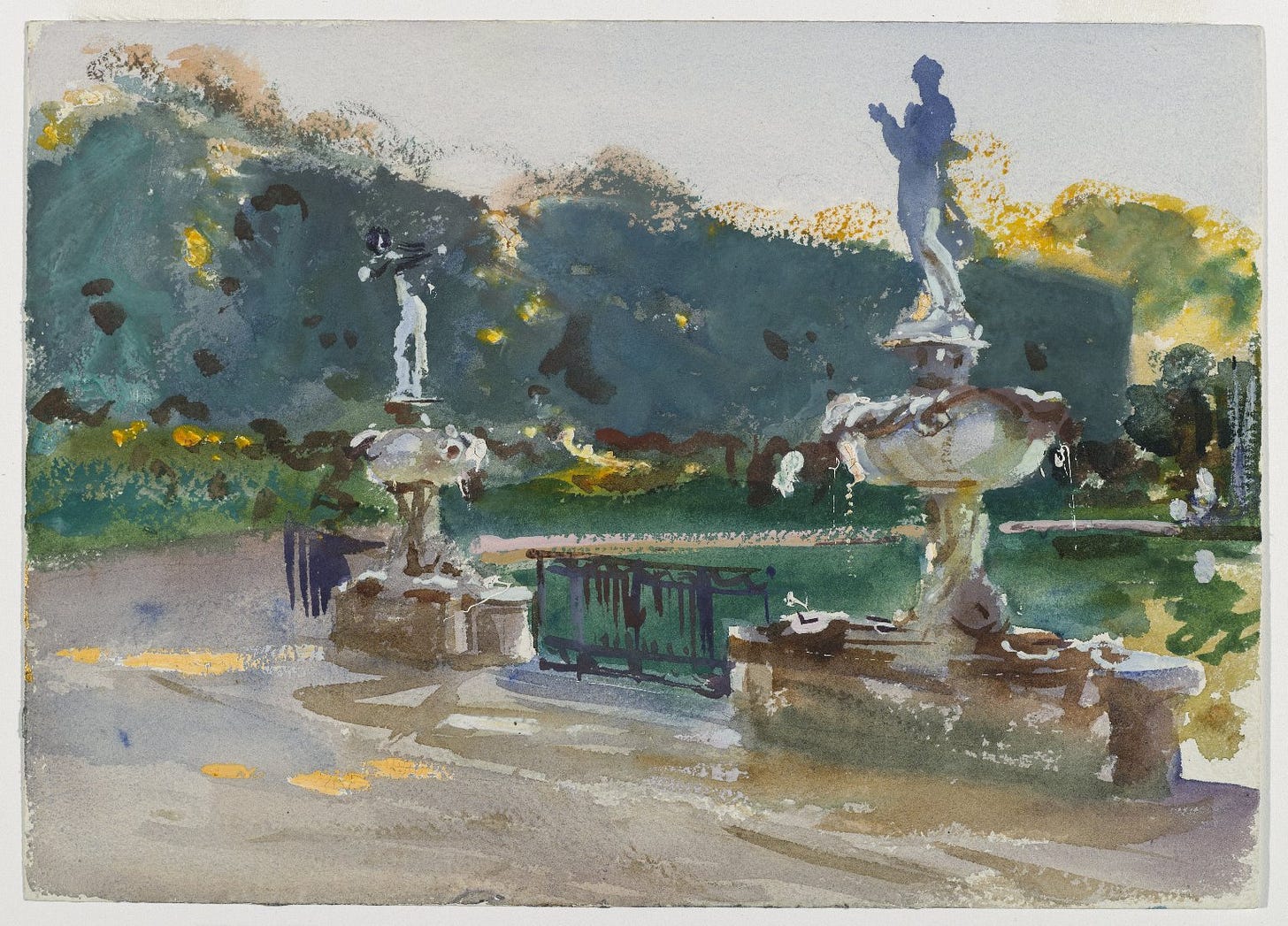

The works he is best known for are these society portraits. Though he was peers and friends with many Impressionists, like Claude Monet, and British art critics accused him of being one, wary of his continental ways. Sargent defended Impressionism and was influenced by many of their methods, particularly the relationship between color and light, which can be seen in his watercolors or the folds of the clothing he painted. Still, the works most seen and talked about by Sargent were portraits, that on their face, depicted a conservative, wealthy world.

But in context, he pushed forward more than it may seem, combining a respect for the growing modernism of the late 19th century with a deep love and knowledge of art history. Of course, there was controversial Madame X, but Edith Minturn Stokes’ depiction in the marriage portrait lines up with the New American Woman of the Gilded Age. She (this new woman) plays tennis, she maybe wears bloomers while riding a bicycle. She can attend college if she is wealthy enough to pay for it and her parents allow it (in the case of Edith, she was rich enough, but she was discouraged from obtaining any higher education). This is not a painting of a wife, it is a painting of a woman, who incidentally has a husband.

Perhaps the most famous marriage portrait of all time, The Arnolfini Portrait by Van Eyck, is so full of symbolism, from either object or perspective, it is widely considered one of the most complicated images in art history. The clothes of the couple, the decorations of the room, the shoes off to the side, the mirror in the background, with carvings around its frame, the poses of the couple, the little dog, and surely even more elements can be imbibed with meaning. The dog in particular is one of the clues that it is a marriage portrait, since a dog is a symbol of marital fidelity, often used in Medieval and Renaissance paintings and decorative arts to signal a faithful marriage.

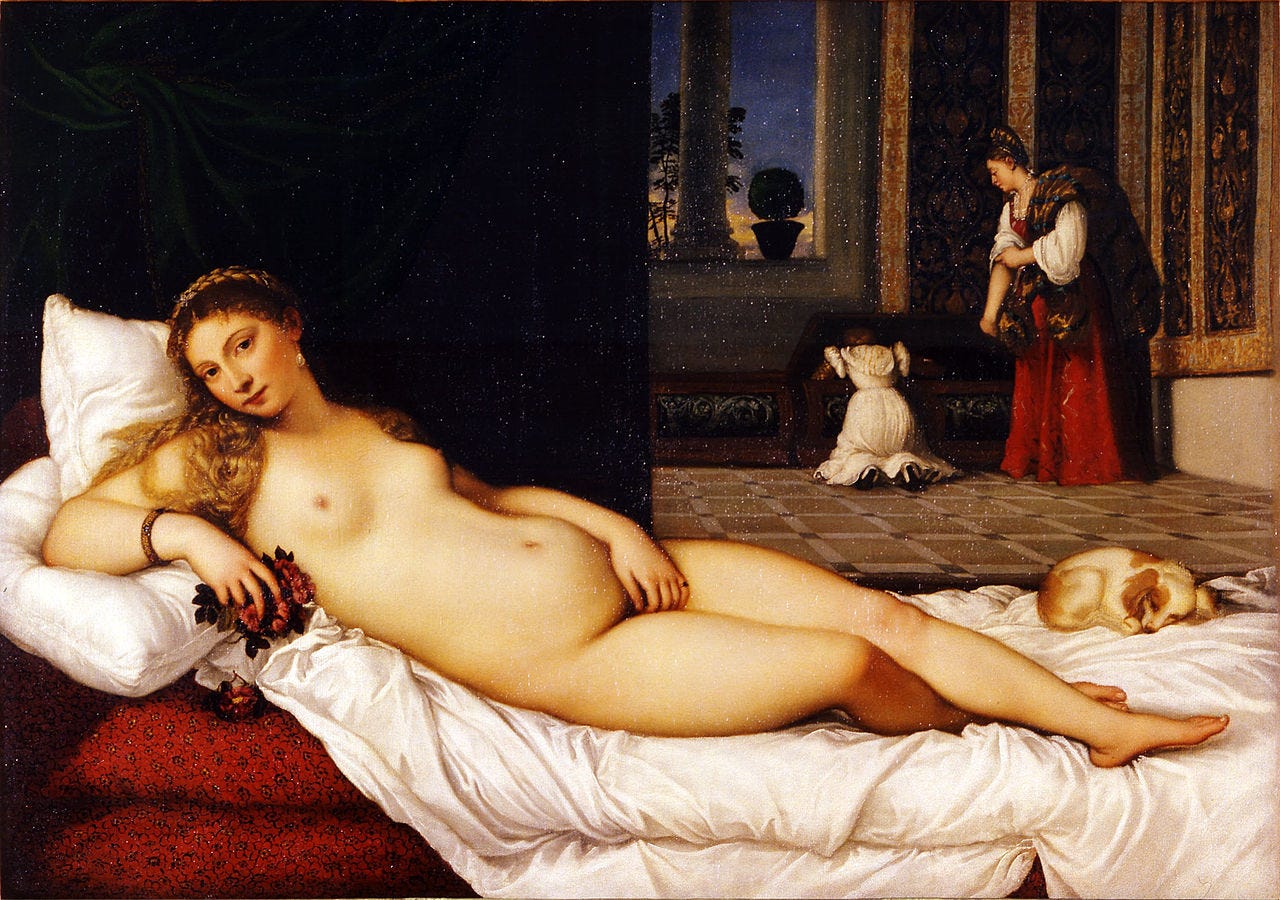

In the case of painting sexual dynamics, a dog can also work as get out of horny jail free card, in the case of Titian’s Venus of Urbino. This one is less strictly a marriage portrait, more a painting potentially in disguise as a marriage portrait.

The boldness of Titian’s Venus, directly looking at the viewer, with her hand above her genitals, and the setting of a 16th-century Italian home, instead of an idyllic, pastoral setting, belays an allegorical interpretation, traditionally expected of nude paintings. The dog, along with the servants going through the trousseau, in the back suggests perhaps, that the weak allegory here, to justify the commission and possession of a painting of a nude woman, is of marriage.

Edouard Manet’s Olympia famously subverts all of the tenuous allegorical release valves of the Venus. The sleeping dog becomes a stretching cat, and the languid, inviting pose becomes confrontational. The servant is no longer looking through a trousseau, but bringing flowers from a client.

As a portrait of a marriage, the Mr. and Mrs. I.N. Phelps Stokes is devoid of these traditional contextualizing narrative elements, that often tell a story of a painted couple, since the couple stands in a vacant, but warm grey and taupe plane. For the Stokes’ the only context of their relationship is how their bodies interact in their posing. Edith’s pose in particular shows a sexual possessiveness over his husband, with the prominence of her wedding ring, even more clear in person, given Sargent’s impasto technique to build up the mass of her left hand, and her boater hat in her right hand, demurely covering what is only hers. She stands aglow on the first plane of the portrait, clearly the main subject, and Isaac stands behind her, endorsing her forwardness, in the shadows.

And he’s her Great Dane! Though unlike in the portrait of the Duke of Richmond and his dog, the stand-in does not look affectionately at his master, rather adopting the confrontational, responsive gaze out to the audience. If Edith’s glow and smirk are inviting and controversial, along with one arm akimbo, Isaac’s direct look, with his crossed arms, is on the cusp of challenging. Sargent paints not just a marriage portrait, but one of art history’s great wife guys.

Often when personal information is included about the subjects of Sargent paintings, it feels framed around tragedy. Painted during a window of great wealth and expansion for this class, the children in particular of the famous parents who commissioned the portraits often have anecdotes of tragedy attached to them. There’s Miss Beatrice Townsend who died only two years after Sargent painted her and her dog. Much is made of the alienating composition of The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, showing four sisters, separated from each other, the eldest two, already in adolescence receding into shadows, whereas the toddler sits in the sunlight. None of the four daughters would marry, and two suffered acute mental health crises as adults.

But something true of Edith and Isaac, and for many of us, is there was tragedy and fortune mixed in one in our lives. They were not able to have biological children, which is often mentioned as the source of their tragedy with the couple is discussed, and was a great source of anxiety and sadness for Edith in particular. But progressively and novelly, they had an open adoption of a daughter, Helen. The birth parents were acquaintances of acquaintances who were British gentry stationed in India and felt uncomfortable raising an infant in the foreign, hot climate. British colonialism notwithstanding, the Stokes’ adoption of the little girl was distinct from a common 19th-century solution of wealthy parents essentially trafficking the children of poor mothers. The Stokes and the birth family would have a continued relationship and the Stokes adored their daughter and the grandchildren she gave them.

The couple was committed to housing and public reform in New York, with Isaac using his architectural skills to make maquettes of tenement buildings and alternative styles of housing, shown in a society exhibit, to encourage his wealthy friends and politicians to advocate for a new model, in the same mode as Jacob Riis’ documentary photography. He would serve on the architectural committee of Governor Roosevelt’s Tenement Housing Commission, leading up to the 1901 New York State Tenement House Act. Edith, for her part, was the president of the New York Kindergarten Association, a group advocating for universal kindergarten and funding these classes for schools when the city could or would not.

Another tragedy that might be pointed to is the couple’s loss of wealth during the market crashes in 1929, which caused them to sell much of their collected art, though the Sargent painting remained in their collection until Edith’s death. She bequeathed it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Much of what was sold off was Isaac’s massive collection of historic material gathered about the history of New York that he collected while writing The Iconography of Manhattan Island, a six-volume work about the architectural history of New York City from the 16th to 20th centuries. The exhaustive volumes often covered materials that were lost since the Stokes team did the original research, meaning it is an instrumental, if labyrinthine, source for these materials now.

Edith passed away in 1938, after a lifetime of chronic illness and a series of strokes. But the attention that Isaac paid to her during this time, in their shrunken scale of life, smaller for economic, health, and age reasons, are some of the most moving images of the couple to imagine. I can make myself cry thinking about the taciturn husband to the vibrant wife, hanging out in Sargent’s studio, even though he doesn’t need to be there, just to spend time with her, becoming the main conversationalist of the pair as her capacity for language diminished. “For the four or five years left to her he spent most of his time at her bedside, reading to her and telling her jokes, and wheeling her through Central Park.”1

In a genre fiction romance novel, the story would end well before Edith’s death. And before Isaac’s, when he was still not quite sure of what his legacy to the world be would, in his diminished circumstances. But the man’s two passions are what he is remembered for, his wife and his Iconography, though perhaps one more publicly than the other, since the portrait is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Still, the anecdote, of the husband taking his place behind his wife, in place of a gigantic dog who never showed up, feels like it is out of a romance novel, and was plucked out of a real-life romance. And documenter of the event was Isaac himself. Writing a memoir called Random Recollection of a Happy Life in 1941, three years before his death, he relates: “I remember Mr. Sargent as a delightful companion and we shall never forget the pleasant mornings in his attractive studios. Mr. Sargent wanted Edith to pose with a Great Dane, but when she was ready to pose he discovered that his friend who owned the dog had left town and had taken the dog with him. He painted me in the painting in three standings, really I was an accessory.”

Recommendations

Love, Fiercely by Jean Zimmerman: A dual biography of Edith and Isaac. Wonderful, if slightly scant when it comes to Issac’s life after Edith, particularly his work with the New York Public Library’s print department and his political relationship with Fiorello LaGuardia.

The Gilded Age on HBO: I mean obviously. I binged this is one weekend with a fever and it is one of my favorite media memories of the year.

Bliss and Dance by Judy Cuevas: Cuevas is one of the best romance novelists at including discussions of visual art and I recommend strongly both of these books about a pair of French brothers, who could not be more different. I will say: these books are very hard to find, particularly Dance, since they are out of print and have never been released as ebooks. I promise there are ways to read these without spending hundreds of dollars on a physical copy that no one should have any moral quandaries about. Both books take place in France at the turn of the 19th century.

One Burning Heart by Elizabeth Kingston: Unrelated to this newsletter, but this is certainly the best romance published this year that I’ve read. I devoured it.

Francis Monroe, The Ghost of Monsieur Stokes, City Magazine, Autumn 1997