non-romance, romance, #15: Certified Copy (2010, dir. Abbas Kiarostami)

forget the original, just get a good copy

This is a non-romance, romance, a monthly feature where I write about something other than strictly romance novels through the lens of romance. They are some of my favorite things to write. No giornata this week—I think it make sense to take a break from these when I have a non-romance, romance out!

background (An American in Paris and Walter Benjamin)

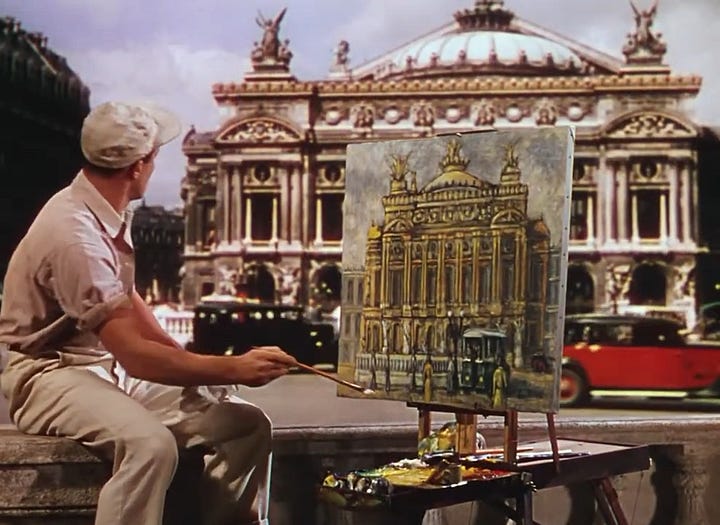

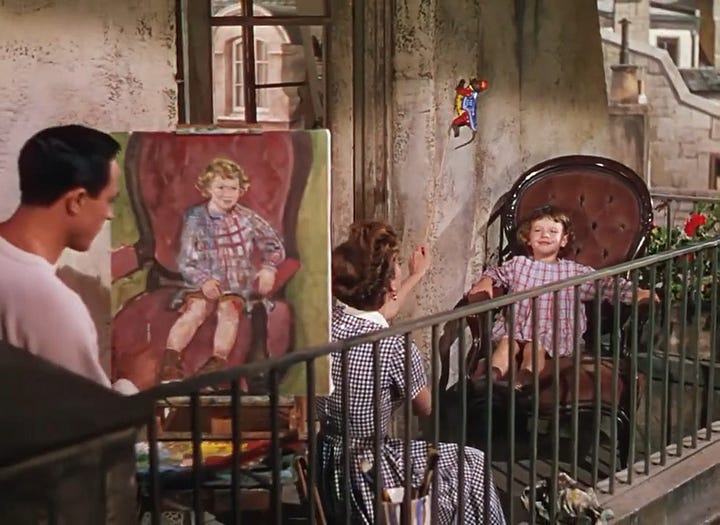

In An American in Paris, Gene Kelly plays a painter named Jerry Mulligan, a former solider who now lives in postwar Paris. Jerry is a not a good painter, possibly the worst artist that any movie asks the audience to think is good. His work is charmless derivative tourist bait with little understanding of perspective. The high point of visual art in the film is the dream ballet, where scenes are based on the works of Raoul Dufy, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, but supposedly this guy’s art (pictured below) is supposed to be in the same category.

It is particularly pointed that Jerry’s art sucks so much because it is art that is so outdated in the 1952, when the film comes out. Jerry’s art is wholesale backwards looking, which even the notion of moving to Paris to study art in the 1950s is. The first half of the 20th century is a time when the center of the art world is moving from Paris to New York, and by 1952, the shift has been made. Alfred J. Barr’s landmark exhibit “Cubism and Abstract Art” at MoMA was over 15 years earlier!

In a sequence that I love, because I love precocious women who studied abroad to look at art, a “third-year girl” approaches Jerry on the street to discuss his art. She says “I can understand disregarding perspective to achieve an effect—but in your case I believe…” before Jerry cuts her off and tells her to move on. The student wants to discuss his work and Jerry wants to sell his art. Which, fair play. When Milo (as in Venus de, played by Nina Foch) approaches, he is more welcoming, contrasting her to the “officious and dull” college student. Milo enjoys Jerry’s work and wants to serve as his patroness (and possibly have a romantic relationship with him). She purchases two of his paintings for an absurd price, outside the realm of his imagination, since he has never actually sold a painting before.1

Milo lavishes praise on the paintings and Jerry says that her compliments make the paintings easier to “give up,” an idiom that surprises Milo. He explains: “Yeah. It's kind of hard for an artist to sell. A writer, a composer can buy a copy of what they create. But, with a painter, it's the original that counts. Once that's gone, it's out of his life.” Despite his terrible art, Jerry gets a major question here of modern art in the first half of the 20th century, central to the means of production of art when things can be seemingly be reproduced so easily.

This question is central to any modern art class (Mona Lisa Smile is set a year after An American in Paris was released). My modern art class syllabus, when I was a third year girl, started with Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Benjamin starts with the history of the human impulse to reproduce: craft, stamping, molds, woodblocks, lithography, photography and the finally film, which reproduces, two-dimensionally, the main sense experiences of being alive: sight and sound unified. Benjamin explores both the reproduction of an a piece of art made without the add of reproductive methods and what he sees as the ultimate reproduction with film.

Benjamin argues that one thing that makes an original is its presence in time and space—the thing can only be in situ in one instance. Though reproduction of art like paintings or architecture can allow people to engage with the original on a different level, either by accessing more detail or expanding the time and space which the art can be seen, like a photograph of a cathedral, Benjamin insists that a reproduction is always a diminishment, that “aura” is lost when something is reproduced.

“Aura” is derived from both the work’s uniqueness and its conversation with the tradition/history that created it at the moment of inception. The ritual, be it religious or aesthetic, gives context to the object and gives it meaning, but that meaning only exists when something is unique. Art forms that are inherently “reproducible” (photographs, movies, recorded music) escape this context and instead are conceived from the jump to be distributed en masse. While the “aura” of a painting cannot exist in this mass forms of art, the reproducibility creates something new. Benjamin says of film:

As compared with painting, filmed behavior lends itself more readily to analysis because of its incomparably more precise statements of the situation. In comparison with the stage scene, the filmed behavior item lends itself more readily to analysis because it can be isolated more easily…By close-ups of the things around us, by focusing on hidden details of familiar objects, by exploring common place milieus under the ingenious guidance of the camera, the film, on the one hand, extends our comprehension of the necessities which rule our lives; on the other hand, it manages to assure us of an immense and unexpected field of action.

He also compares film to psychoanalysis, giving fractional insight into fractional movements of the human face and body, just like psychoanalysis aims to give insight to the fractional thoughts and emotions.

Benjamin, a Jewish German man who died by suicide in 1940 when he was threatened with expatriation from Spain back to occupied France, a move that he believed would lead to his incarceration at a concentration camp, explicitly links his theses to anti-Fascist politics. He sees Fascism co-opting the ability of mass market art, under the auspice of individual “expression” without also adopting the mass’s right to change the property structure of the Fascist state.

“Fiat ars—pereat mundus,”2 says Fascism, and…expects war to supply the artistic gratification of a sense perception that has been changed by technology. This is evidently the consummation of “l’art pour l’art.” Mankind, which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art.

an original copy

Certified Copy is filled with moments of romance that come from deep understanding of a partner. One that I love is the story that Juliette Binoche’s unnamed character (credited as the anonymous “Elle,” so this is what I will call her) tells James about her sister and her stuttering husband. Elle thinks her sister is a fool and her husband a dolt. “She’s married to the simplest man a live. To her, he’s the best man alive. He stammers. M-m-m-m-m-m-m-Marie! For her it’s a love song.” James retorts, “I can understand that. He’s lingering over her name.” Elle immediately embraces James’ framing and turns on her negative take on her sister, her tone and face warmer when she says “she insists they got it wrong, when they registered her name at birth, you know, she said the right spelling is “m-m-m-m-m-m-Marie.”

The sweetness here is both in Marie and her stammering husband and Elle and James’ shifting together toward a kinder understanding, over a matter of seconds. It is like James knows exactly how to turn Elle’s bitter and exasperated take on her sister into an expression of affection.

But James and Elle, as far we know, have just met. James Miller is an English author visiting Arezzo to promote his new book, Certified Copy (Copia Conforme in the Italian translation, seen on screen). The woman attends a talk and book signing with her son, and though she has to exit early, she leaves her phone number with James’ translator. Off-screen, presumably they arrange a meeting at her antique shop because he arrives there later and they seem to have planned the meeting. Rather than putter around amongst the antiques, they go on a drive. Elle is driving James up a Tuscan hill during the exchange, which is about a half hour into the film. James has agreed to go on the adventure with her, having the day free, but he says he must return to town by 9pm to catch his train.

In the first half of the film, Elle and James discuss the thesis of his book, which is deeply connected to Walter Benjamin’s work, though coming to a different conclusion. James’ Certified Copy posits that questions of authenticity, or what Benjamin would call aura, are ultimately meaningless because even “original” art is a copy of the “real” thing. La Giaconda’s smile is just a mimicry of the smile of Lisa del Giocondo. Elle does not always agree with James as he is explaining his premise, creating strain in their acquaintanceship. But they explore their difference of opinion on the value of originals, copies and “original copies.” My experience as a viewer of film, all three times I’ve seen it, is a deep anxiety that either James or Elle will abandon each other or endanger each other, which becomes either harder to do or potentially more devastating as they become more and more entrenched in each other’s lives, over the course of a only a few hours.

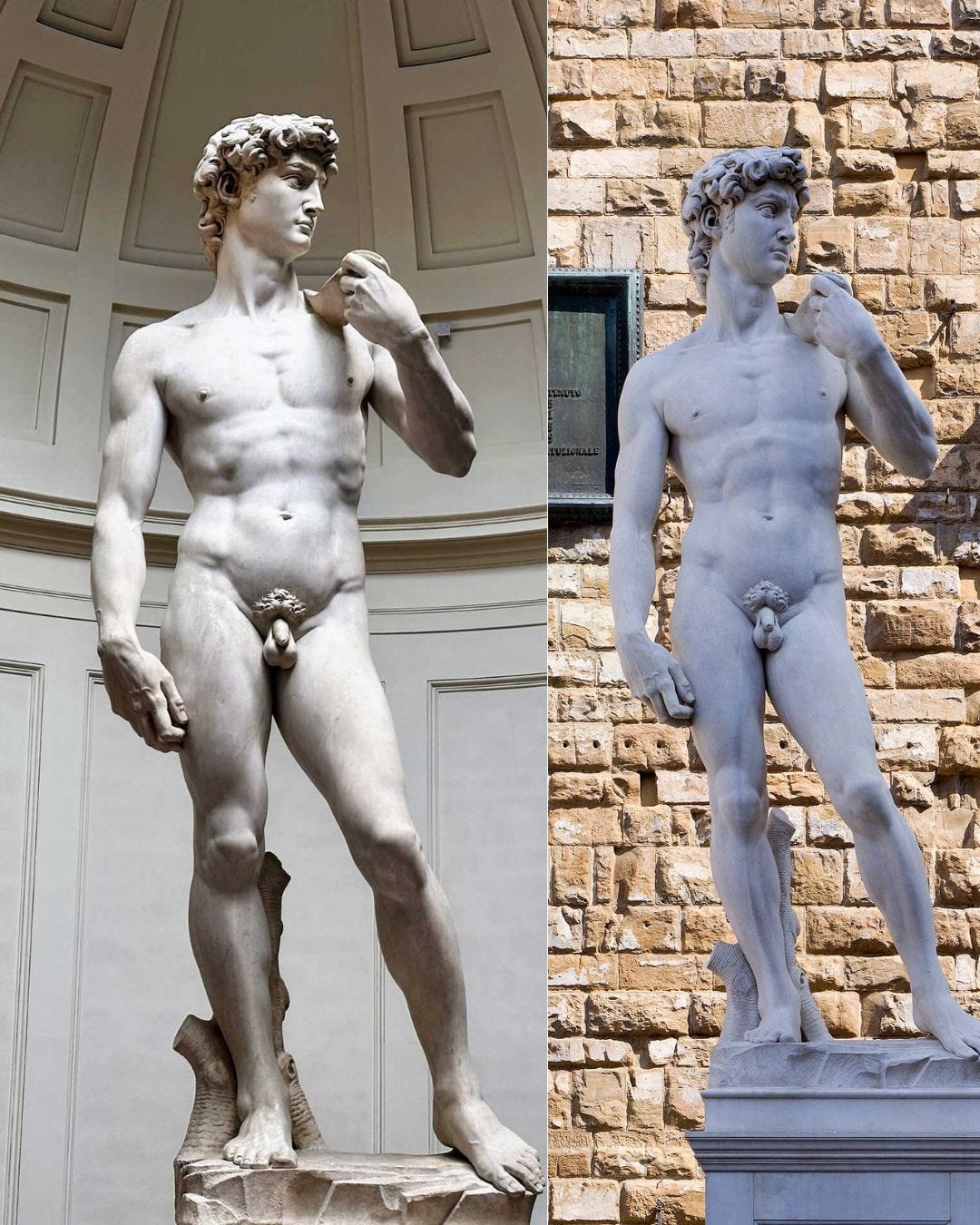

The great conceit of the film is revealed about half way in. They’re in a cafe, Elle has asked about James’ anecdote about getting the idea for the book that he shared at the book talk. He had mentioned where he was, but not the inciting incident. He was in the Piazza della Signorina, watching a mother and child who spoke French, in front of the David statue. The theme of authenticity and copies is triggered here because the David in the Piazza is a fake. The Piazza was the original location of the statue, until 1873 when small cracks were noticed. That summer, the statue was slowly moved from the Piazza to the Galleria dell ’Accademia, about a 1500 m walk that took nearly two weeks.

James had seen the mother and son in Florence before, on their route walking by his apartment daily. In the Piazza, he was convinced that the mother told the son something about the statue, without revealing that the one he was looking at was a reproduction. The son’s face at the statue supposedly inspires the book about what value can come from a copy, particularly a copy that is given weight and authority by some power (like the city of Florence making the decision to exchange the Davids.)

Though never made explicit, there are hints that the mother and the son in the story are Elle and her son. She pointedly reveals in the next conversation that she used to live in Florence, she has an outsized, tearful reaction to the story as James tell it, and James mentions that the mother and son spoke French, though he never makes an indication that he recognizes her as the woman. This would be a coincidence on a massive scale at this point in the narrative, but what follows between James and Elle, throws into question what anybody’s relationship is to each other.

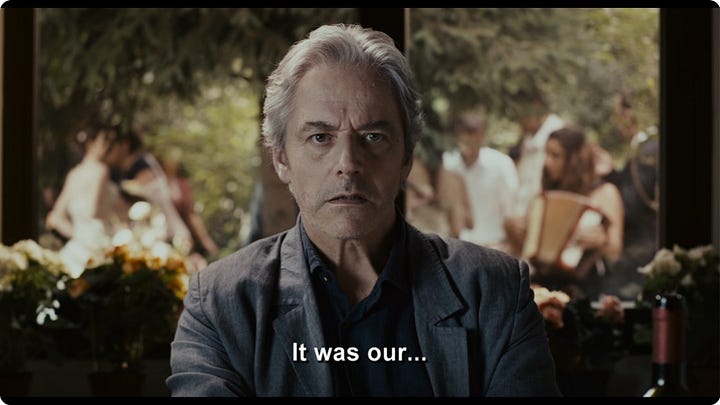

Just after he explains the look on the son’s face looking at the statue, James gets a phone call and steps out. The woman working at the cafe mistakes James for Elle’s husband and Elle does not correct her, instead taking the opportunity to dish about the irresponsibility of absent husbands in Italian (a language James does not speak fluently). The lie pours out of Elle incredibly organically. She peppers in highly specific details, like about how he shaves every other day, without fail, to the point that on their wedding day, a no-shave day, he had stubble. Elle discloses her fib to James, in English, when he returns. Instead of rebuffing her or being confused by this intimate lie, James plays along with the play acting, saying “obviously we make a good couple.”

The woman at the cafe was surprised that James doesn’t speak Italian, since his “wife” and “child” live in Italy, and when he returns he offers as an explanation “My family live their lives and I live mine. They speak their language and I speak mine.” As he is saying this, Elle gets a phone call from her son and storms out of the cafe. During that phone call, Elle speaks both to her son (in French) and to James (in English), implicates James in how the son was raised and expressing disappointment in his comment to the woman at the cafe. James takes issue with this, not because it is false, but because he thinks it is unfair.

From this point forward, only micro expressions might indicate to the audience that Elle and James are not actually married. They play act not only at being currently married, but at having a shared history. In fact, there are many moments where the play acting is so organic, so real that the viewer questions if the first half was the put-on. For example, at one point, Elle caresses James’ face, asking him why he couldn’t shave today, on their 15th wedding anniversary, and he responds that it was a no-shave day. That fib, to the viewers at this point, is an invention of Elle that James supposedly was not privy to. But he is able to access that past, someway, whether it is real or fake, to respond to her without breaking the rules of their shared reality.

The shared history, real or imagined, means that they are not acting as husband and wife in order suppress something or access something fake or avoid reality. This is not “pretend to be strangers in a hotel bar in order to have hot sex.” Instead, the play-acting makes Elle and James confront deep-seated anxiety and self-consciousness. They speak to each other cruelly and callously, in a way that you might when you are clawing at yourself and someone you love, who by necessity and desire is close to you, catches a stray. While my experience as a viewer is anxiety about one character dropping the curtain before the other is ready, neither really seems to threaten that at any point, until the possibly the last bit of the film, when James points out that he must take his train at 9pm. The film ends with the church bells tolling 8pm and James leaving the bathroom, the viewer unsure if he also leaving Elle.

Very little in the film is not doubled/copied in some way. Multiple viewings reward noticing moments in the “stranger” half of the film being answered, redoubled or interpolated in the “romance” half of the film. Beyond that, the film itself references and copies many great romance films. One obvious one is Journey to Italy (1954, dir. Roberto Rossellini), which is about a married couple, an European wife, Katherine, and an English husband, Alex, taking a trip to Italy. Their marriage is strained and the trip only exacerbates mutual misunderstandings.

Near the end of the film, the couple agrees to divorce, but in the moment that feels the most like Certified Copy, Katherine is swept away in a processional, and when Alex finds her again, they embrace and reconnect, seemingly without a catalyst. The experience is that despite watching the squabbles and cruelty on the trip, we cannot have access to the whole of this relationship. The mundane boredom and strain that we see is narratively a sign of distress, signally the downward arc of this romance, but for the couple, it is something else, never voiced. More of the references, explicit and implicit, to other romance films are explained here.

But in Certified Copy, the viewers are under the impression that we have had access to the entirety of this relationship, for most of the film, and the impulse is to try and square the second half “play-acting” with the first half “truth,” until we get to the point where enough signals have triggered a total disconnect in that binary, of one being true and one being false. The tonal shifts, that work primarily because of the virtuoso performance by Juliette Binoche and William Shimell (primarily an opera singer, this is his first film role!), stir up questions of what is real and what is a copy for the viewer, but Elle and James never struggle with what level of abstraction and fiction they are in.

The fact that this is a film, and not any other media, speaks to Benjamin’s thoughts about the nature of film as the ultimate reproduction. Elle and James may be reproducing a marriage (or reproducing an estrangement), but Juliette and William are doing the same. But irrespective of the “reality” (a boring question) of the nature of their relationship, Elle and James are in the midst of a romance, working through together how to speak to each other, how protect themselves while leaving themselves open to the other person.

The other romantic gesture that I love, besides “m-m-m-m-m-m-Marie” happens immediately one of the cruelest scenes in the movie. James and Elle goes to a restaurant in a small hill town, but it is 5pm, too late for lunch, too early for dinner. The restaurant is open, but they get what James perceives to be poor service. Elle excuses herself to go the bathroom and puts on lipstick and earrings, but returns to an even crankier James, upset about the wine they ordered being corked. Their discussion devolves into cruel jabs, opening up old wounds about affection and attention and parenting. The whole scene is filmed straight on, facing the actors, so at the camera flips back and forth, the shot is the POV of the other character. Like Benjamin said, we can see the precision of expression through this method of filming.

After the first half of the argument, James plaintively says “if you aren’t even going to try to see things from my point of view, what’s the point?” and leaves Elle crying at the table. He returns, but this time he restarts the argument with much more anger, and when he leaves, he storms off, passive aggressively “apologizing” for his very existence and for their fifteen years of marriage. While the arguments are different in their content, it is like they run it back, trying a different method to resolution. Elle’s reaction to this iteration of James leaving is minimal.

When Elle leaves the restaurant, James has not gone very far, sulking just outside. Elle hands him a piece of bread and James slowly walks behind her as she walks back into town.

The petulant, hangry behavior here is by no means attractive. But this is not a romantic gesture of a courtship, this is a romantic gesture, a bid for connection, in a well-worn relationship. Despite the cruelty just exhibited on both sides, poking insecurities and anxieties, she offers him a snack and he accepts and walks with her again. It’s Lucy and George in A Room with a View,3 leaning on the parapet, “There is at times a magic in identity of position; it is one of the things that have suggested to us eternal comradeship.”

In Certified Copy, we’re watching a pair of people line their bodies, language and emotions up with each other, attempting to transfigure that union into more than the sum of its parts. It’s play-acting whether their relationship is “real” or “fake” because this process is always performance. The painting is a reproduction of the real thing and the self in the relationship is a reproduction of the original self, removed from its original time and place to create accessibility for someone else.

Jobless behavior.

Let art be done, and the world perish.

Like I wasn’t going to bring up A Room with A View.

I loved Certified Copy when I saw it back in 2010 or so (it has been a while)! This was so fun to read and think about again—I really want to go back to it now. I think it also worth pointing out that William Shimell is an opera singer, so the way that he translated (copied?) his particular set of theatrical skills to film was pretty darn compelling. And putting an opera singer against Juliette Binoche! Kinda brilliant as a casting choice.

I also remember feeling the deep anxiety you mention and would point to Before Sunrise/Before Sunset as similar experiences. There is something so romantic about the urgency and intensity of the long-and-yet-limited encounter in all of those films! Thanks for the thoughts, as always.