non-romance romance, #2: A Day in the Country (1946, dir. Jean Renoir)

adaptations of weather and consent

This is the second issue in an ongoing, untethered series where I write about things that are not romance novels that I think romance novel readers might enjoy, with the genre as a lens. The first issue is here and is about The Apprenticeship, or the Book of Pleasures by Clarice Lispector. That one was also about A Room with a View, which is also kind of what this one is about.

The Newgate series is still happening! I’m just getting my citations in order for my next part, which will be out in early February.

Content warning: I discuss a short story and film within this letter that depict sexual encounters between a man and a woman that are somewhat ambiguous in their violence. I reference the potential of the scene being consensual or violent, an ambiguity available in fiction, not in real life. Both the short story and film are euphemistic and somewhat distant in their depictions, leading to this interpretation on my part.

In A Room with a View (1908), Lucy Honeychurch is always looking at things from the inside out. She’s also “inclined to get muddled,” according to Mr. Emerson. Not to rely on the title of the novel too much, but there’s a reason that Lucy Honeychurch does not fall in love with an Italian lover, though that is an available plot to Forster (Lilia Herriton and Caroline Abbot both do it Where Angels Fear to Tread, though the results are decidedly tragic). The narrative of A Room with a View does not even really consider it. Lucy’s options are English Cecil Vyse, who she associates with a drawing room, a room with no view, and English George Emerson, the man who gives up his room with a view at the Italian pensione in the first chapter so that she might have one. To fall in love with an Italian would be to ruin the Englishwoman’s view out the window.

Neither of these Honeychurch associations are necessarily how the men view themselves--Cecil wishes he were associated with the open air, perhaps the Italian open air, constantly begging comparisons to Italy itself, though the narrator links Cecil to the fastidious and unmoving saints of a French cathedral. George Emerson perhaps struggles with the directness of the sky-view most closely associated with Italians and his father in the book, though that always seems to be what he is reaching for. In practice, he is the compromise of the room with a view.

“My father”—he [George] looked up at her (and he was a little flushed)—“says that there is only one perfect view—the view of the sky straight over our heads, and that all these views on earth are but bungled copies of it.”

“I suspect your father has been reading Dante.” [responds Cecil]

Two incidents happen in Italy that push the action throughout the novel--the murder in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence (discussed in the The Apprenticeship edition of this series) and the kiss on the hills of Fiesole. Though in an open field of violets in the hills, when George is about to kiss Lucy, “the bushes above them closed,” recalling the exterior/interior collapse that indicates throughout the novel that Lucy is just where she ought to be. Later, when reporting the details of the incident to Charlotte Bartlett, Lucy’s cousin/chaperone/scold, Lucy describes the scene thusly: “The sky, you know, was gold, and the ground all blue, and for a moment he looked like someone in a book.” Turned upside down, turned inside out, George is the man in front of Lucy and he’s the man in a book.

Lucy’s assessment of the kiss and her place in the action is fractured and discordant. There are all these narrative signals that George is in line with Lucy--their bodies parallel each other in different scenes, he’s compared to the room with a view that she wants, she reacts strongly to the art that is most directly associated with him (the mortal nudes on the ceiling of the Sistine chapel) by the narrator.

But the narrative voice laments Lucy’s internal dialogue, colored by Cousin Charlotte, to decide that the kiss was a “grievous wrong.” Like during the moment of the kiss itself, Lucy is on a precipice while assessing it, and Charlotte’s declarations of wrongdoing push her over the edge into discomfort and anger at what has happened.

For a moment the original trouble was in the background. George would seem to have behaved like a cad throughout; perhaps that was the view which one would take eventually. At present she neither acquitted nor condemned him; she did not pass judgement. At the moment when she was about to judge him her cousin’s voice had intervened, and, ever since, it was Miss Bartlett who had dominated; Miss Bartlett who, even now, could be heard sighing into a crack in the partition wall; Miss Bartlett, who had really been neither pliable nor humble nor inconsistent. She had worked like a great artist; for a time—indeed, for years—she had been meaningless, but at the end there was presented to the girl the complete picture of a cheerless, loveless world in which the young rush to destruction until they learn better—a shamefaced world of precautions and barriers which may avert evil, but which do not seem to bring good, if we may judge from those who have used them most.

The rest of the novel is Lucy working her way back from this borrowed judgment, back to her unsullied assessment of the kiss on the hillside.

In Une Partie de Compagne (or A Day in the Country) by Guy de Maupassant (1881), the sun beats down on the city family visiting the country, leading to social norms slipping away--the women swing on a swing set to cool down, a chance meeting occurs because there is a lack of shade and two men give up their covered spot to the women, the effects of alcohol are more acutely felt in the heat, clothes are loosened to find relief, boat rides are taken with strangers.

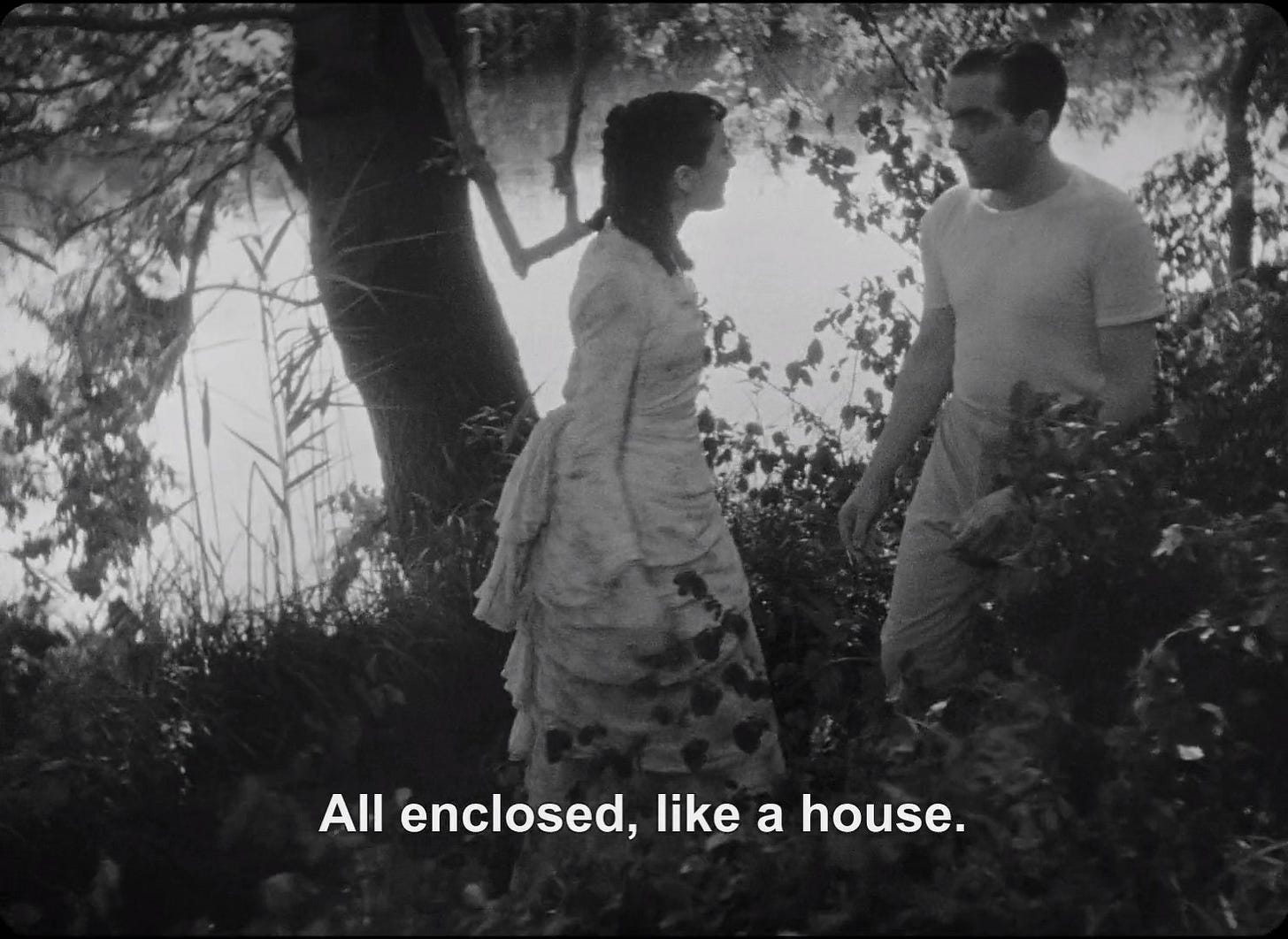

Filmed in 1936 and released as an incomplete film a decade later, the adaptation, directed by Jean Renoir, is about 40 minutes long. The plot is adapted fairly literally. A family goes for a country excursion. There is the father, the mother, the daughter, the grandmother and the tag-along apprentice. The apprentice is fleshed out to be a buffoon of sorts and the local boaters are given more dialogue directly with each other in the film.

Once they are in the country, the mother and the daughter pique the interest of two sailors from the area. They offer to take the pair out in their boats, individually. All of this leads to the daughter of the family making love with (or kissing, or being kissed by, or being seduced by, or being raped by) her local boater. They sit on a clearing in a forest, below the boughs of a tree, and listen to a nightingale.

The experience of sitting below the nightingale moves the girl to tears. The boater works up to an embrace of the girl, with her moving his arm away, repeatedly, but he eventually kisses her. She reacts with physical squirming. In the story: “Elle eut une révolte furieuse et, pour l’éviter, se rejeta sur le dos.”1

The nightingale’s song is the primary euphemistic descriptor of the actions below in the de Maupassant story, leading to the ambiguity of the nature of the violence or romance of the encounter. The song is described in ecstatic terms, juxtaposed with the potential violence below it and the symbolism of a nightingale’s song being a lament, particularly after sexual violence. The daughter returns to the country a year later and meets her lover or assailant again while her husband sleeps. She assures the boater that she thinks of the incident every night, and then they part once more when her husband wakes up.

Like in the kiss on the hillside in Fiesole A Room with a View, the incidents above happen as exteriors become interiors. In both story and adaptation, Henri refers to the setting of the kiss below the nightingale, as “son cabinet particular" (his private room). And then in both story and the adapted film, there is an acquiescence of sorts--in the story, “affolée par un désir formidable, elle lui rendit son baiser en l’étreignant sur sa poitrine”2 and in the film, she throws her arm around Henri.

A Room with a View’s kiss is generally seen as romantic, though the reader is told that Lucy decides, though influenced by Charlotte, that it was a “grievous wrong.” We read the novel to watch her realize and return to her own assessment of what the kiss means to her. But Henriette’s changing and ambiguous assessment is less clean, particularly in the film, where the nightingale is diegetic sound over the scene of seduction, compared to the short story where total narrative focus shifts to the nightingale’s song as euphemism.

Additionally, both written texts have tension between their adaptive choices, some of which needed to be made because of natural realities outside of the control of the film makers and the clues of consent available to reader vs. viewer.

In A Room with a View (novel), the kiss takes place on the hillside in the spring, with violets on the hill. George has previously gifted violets to the Misses Alan, another set of residents as the pensione in Florence. The reception of the gift is, at first reporting, chilled, but then romanticized in retelling. Either way, the gift signals his openness that is characterized again and again by the narrative as a virtue. Lucy is picking violets when she is led by the Italian driver to George on the hillside and the violets create the sea of blue that flip the cosmic order of the sky and land leading up to the kiss.

She did not answer. From her feet the ground sloped sharply into view, and violets ran down in rivulets and streams and cataracts, irrigating the hillside with blue, eddying round the tree stems collecting into pools in the hollows, covering the grass with spots of azure foam. But never again were they in such profusion; this terrace was the well-head, the primal source whence beauty gushed out to water the earth.

Standing at its brink, like a swimmer who prepares, was the good man. But he was not the good man that she had expected, and he was alone.

George had turned at the sound of her arrival. For a moment he contemplated her, as one who had fallen out of heaven. He saw radiant joy in her face, he saw the flowers beat against her dress in blue waves. The bushes above them closed. He stepped quickly forward and kissed her.

The film retains this gifting of blue flowers from George to the Misses Alan, (the violets become cornflowers), but though the film crew looked for blue flowers when filming the kiss, they could only find poppies on the hill. The substituted flower is not without meaning though. The red on the ground recalls the spilled blood of the murdered Italian in the piazza, along with possibly the redemptive blood of Christ (red flowers on the ground symbolizing his displaced stigmata, a theme of imagery, including below in Fra Angelico’s Noli Me Tangere from the Convent of San Marco in Florence).

The seasonal necessities of adaptation seems to push the scene towards a life-overturning violence, but perhaps not necessarily a harm, linking the kiss to George’s revelations on the parapet over the River Arno after the murder in the square. What is lost in the adaptation is the interiority of Lucy assessing and reassessing the context of kiss, her consideration of a world turned upside down, with a narrator acknowledging incorrect conclusions she is coming to and will eventually correct, along with the extension of the link between George and the cornflowers/violets. But gained is another rich visual parallel that is novel to the film.

Similarly the adaptation of A Day in the Country retains the precipitating weather event: the sun leading to the excursion, the accompanying heat leading to melting of social bounds and removal of clothing. After Henriette and Henri part in the short story, “the blue sky seemed to have grown dimmer; they did not feel the glare of the burning sun; they were aware of solitude and silence. They walked quickly, side by side, not speaking, not touching, for they seemed to have turned into irreconcilable enemies, as though a sense of loathing had come between their bodies and hatred separated their minds.”3

But in the film after the kiss, with the nightingale above, the resistance and then acquiescence, Henriette begins to cry, and then there’s a cut to the pair reclining and standing up, suggesting more intimacy beyond the kiss. Instead of following the couple out of the enclave, the rest of the shorts of the sequence are grasses leaning from gusts of wind, clouds quickly rolling in above and finally, pouring rain on the river itself, filmed presumably from the back of the boat, as the camera rushes down the center of the river itself.

Lost is the individual response of the couple to the dimming sun, that might be metaphorical in the story, along with the euphemistic description of the nightingale’s song that does the heavy lifting of creating ambiguity surrounding the pleasure/violence of the encounter. But gained is the visual metaphor between Henriette’s tears and the punishing rain on the landscape.

I’ve written before about how consent knowledge is managed for readers’ in romance novels and how authors might use the confined structure of dual POV to retain the drama of a bodice ripper, with modern consent politics. Questions of adaptations don’t really come in genre fiction spaces in my experience--some romance novels have been adapted for film, but none of my favorites have (how good could a Lord of Scoundrels movie be though? Loretta Chase is the author I would be dying to see adapted; I think her movies are so cinematic). But thinking about these responsive choices to form and environmental necessities that change these movies that I love from their sources helped me think about the first level choices that have to happen in the novel form, of what information from whose interiority is shared with the reader.

A Day in the Country and A Room with a View are streaming on Criterion Channel and HBOMax and I recommend both heartily.

She revolted furiously, and to evade, threw herself on her back.

Maddened by strong desire, she kissed him back, hugging him to her chest.

Translation by David Coward