O rocks! Tell us in plain words

Ulysses, episode 4, Calypso

In which I reveal my messy little handwriting. Post too long for email, but it’s because I included pictures! All past updates about Ulysses reading are here.

I almost never buy new books.1 I am a librarian and believe in using your public library for all its worth, plus I have access to the resources of a large academic library. This lack of consumption comes in part from a place of great privilege to work around books. Other things that help keep my new book habit at bay: I read mostly older historical romance novels, so I buy them on eBay or Thriftbooks if I want a physical copy, but for the past four or so years, I’ve been very happy to read on my phone.

But after I finished War and Peace2 last year, I was frustrated with what I had done to myself. My notes on the novel were left in the following formats: highlights on Libby, highlights on Hoopla, handwritten in various notebooks that I try to turn into commonplace books, but are mostly just “the piece of paper that was nearest to me” during times when I had checked out a hard copy from the library, and about 30 TikToks that I made between November 2023 and February 2024. This was one reason that I am doing these bookly updates here—the ephemera of it was a little too ephemeral for me. And I bought a new, paperback copy of Ulysses that I’ve been carrying most places with me.

My relationship with annotation is long, though not particularly formal. I read the phrase “a carnal love of books” in Anne Fadiman’s Ex Libris: Confessions of a Common Reader when I was 13 or 14 and felt an immediate kinship. My father has whatever the opposite of a carnal love of books is, though he has the charming habit of using whatever piece of paper is nearby as a bookmark and then putting a book back on a shelf, sometimes to be revisited years later, picking up exactly where he left off. But I don’t think he has ever written in a book. Which is a shame because he writes like an architect.

My mother, with her graduate degree in English, is closer to my messy love of books, though she is much more systematic about them than I am. One of my prize possessions that I would save in a fire is her graduate school copy of Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov, with its curled-up cover and her Flair3 pen annotations. I also have the sense memory of her big Oxford edition of the Complete Works of Shakespeare, which has beautifully thin pages that click when you turn them. She read this book so often, the cover of this book came off at some point, and my father had it rebound for her.

With Ulysses, I wanted to impose at least some bounds to my scattershot notes system,4 so that if/when I read it again, I have some connection to my first round of thoughts.

I can’t quite give up the loosey-gooseiness of just writing on a nearby piece of paper, so I’ve started keeping notes on a 3x5 Post-It note, one for each episode. Post-its are not best archival practices, but it’s a paperback copy of the 43rd printing of a book from 1922. I would not put Post-Its in a vintage romance novel for preservation reasons and I would never use “tabs” to annotate a book because implementing a color-coded system seems like a headache. But Godspeed if that is your ministry.

My adjacent Post-It for episode 4, “Calypso” (pictured above) reads:

Phantom Thread/TPF

Zionism_______________

orientalism (pg. 57)

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

____________________

tailgate

Leopold’s dream/colonizer

reality

island nature of Ireland

Lucia Joyce

abject/bodily fluid

newspaper

Jasper Johns

Leopold leaves + then comes

back

why did I think Stephen’s

nose-picking would be the

grossest thing [in the book]

Episode 4 is a sort of new beginning in the book since we’ve changed focus from Stephen to Leopold Bloom and restarted the clock on Bloomsday,5 so for this episode’s newsletter, I thought I would annotate some of my annotations for you.

Phantom Thread/TPF

This is a code for something I want to explore/track in future episodes or go back and look at. “TPF” stands for The Passionate Friends, which is a David Lean movie that Paul Thomas Anderson pretty directly references in Phantom Thread. All this means is I am interested in moments where Leopold’s first-person perspective shifts to third-person perspective, especially moments where you can’t tell this is happening until after it is over. Phantom Thread and The Passionate Friends both have moments where there’s a slip between voiceover and dialogue, which is disorienting on first viewing. The label from the “technic” section of Gilbert schema there is “narrative (mature).” What this looks like is more free indirect discourse than Stephen’s episodes, which were either most external through dialogue (Telemachus, Nestor) or almost all internal (Proteus). Leopold is described in the third person almost in the same moments he thinks in the first person.

On the doorstep he felt in his hip pocket for the latchkey. Not there. In the trousers I left off. Must get it. Potato I have. Creaky wardrobe. No use disturbing her. She turned over sleepily that time. He pulled the halldoor to after him very quietly, more, till the footleaf dropped gently over the threshold, a limp lid. Looked shut. All right till I come back anyhow.

Zionism____________

What I meant by the line after “Zionism” is I wanted to read what other people had to say about the presence of Zionism in this chapter and Joyce’s relationship to Zionism in general. Leopold6 sees an advertisement for the purchase of land in Palestine from a company based in Berlin. The promise is that you will be sent crops (olives, oranges, almonds, citrons) for your investment. Leopold has already been romanticizing the Middle East, imagining on his walk, walking through a foreign market. This passage is what my orientalism (pg. 57) note refers to, along with “Leopold’s dream/colonizer reality.” But while considering the advertisement, a cloud passes over him7 and his imaginings of Palestine turn dark and deadly:

No, not like that. A barren land, bare waste. Vulcanic lake, the dead sea: no fish, weedless, sunk deep in the earth. No wind could lift those waves, grey metal, poisonous foggy waters. Brimstone they called it raining down: the cities of the plain: Sodom, Gomorrah, Edom. All dead names.

Leopold also thinks of Dlugacz, his butcher, as an “Enthusiast” which my copy of Don Gifford’s annotations tells me signals that the butcher is a Zionist. He also thinks of his butcher as “Moses Montefiore,” a 19th-century Zionist.

I started with Blooms and Barnacles contextualizing the references here and listened to their podcast about Agendath Netaim, the referenced company that is selling the land. The episode discusses Bloom’s pretty apathetic relationship to Zionism—he thinks “Nothing doing.” when thinking about the economics of the scheme and “Well, I’m here now” when his fantasy of Palestine becomes darkened, asserting the Irishness of it all.

I know the question of Leopold’s identity comes up again—what does it mean to be Jewish and Irish? Stephen in the first episode mentions that he, as an Irishman, has two masters: the English government and the Roman Catholic church. Leopold’s Jewish identity complicates that. I’m not going to solve this right this second, so I’m leaving some things unexplored in my annotation of my annotation here. Leopold participates in the British fantasy of Orientalism as he daydreams, and even is attracted to his wife’s Orientalized qualities (she was born in Gibraltar and her mother was Spanish). But Leopold is also going to be the Other for some of the characters he meets.

I’m having to remind myself that the book is set in 1904, and written after 1916. So Joyce is doing a historical fiction here, where Leopold and Stephen don’t know that Easter Rising is going to happen. And Joyce doesn’t know that the Nakba in Palestine or the Troubles in Ireland are going to happen. So my intuition about what it means that Leopold, when his mind wanders to Palestine with a cloud above head, thinks of a land that is desolate, may be projecting an image that is outside the scope (and reading a more sympathetic to my politics’ position in Leopold). This is all to say, I’m probably going to pick up a book about 20th Century Irish history and possibly read more about Zionism in Ireland, because, of course, I need more supplemental texts.

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn from 1943 by Betty Smith is my vote for the great American novel. I was reminded of it here because Leopold goes to buy meat and also thinks about day-old bread, which is what his wife, Molly, prefers to eat. In the opening chapter of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, the young heroine, Francie Nolan goes to buy tongue and day-old bread. At the bakery, she sees a very old man and his old body makes her nervous until she thinks about how much his mother must have loved him as a baby. Just the process of paying for meats and bread with pennies and waiting in line and thinking about your fellow travelers aligned the two scenes for me. But I also had thought about Francie’s old man in an earlier passage.

In episode 2, “Nestor,” Stephen, when looking at his awkward student who can’t manage his sums, thinks about the student’s mother’s love, though it quickly turns to anxiety and guilt about Stephen’s mother:

Ugly and futile: lean neck and tangled hair and a stain of ink, a snail’s bed. Yet someone had loved him, borne him in her arms and in her heart. But for her the race of the world would have trampled him underfoot, a squashed boneless snail. She had loved his weak watery blood drained from her own. Was that then real? The only true thing in life? His mother’s prostrate body the fiery Columbanus in holy zeal bestrode. She was no more: the trembling skeleton of a twig burnt in the fire, an odour of rosewood and wetted ashes. She had saved him from being trampled underfoot and had gone, scarcely having been. A poor soul gone to heaven: and on a heath beneath winking stars a fox, red reek of rapine in his fur, with merciless bright eyes scraped in the earth, listened, scraped up the earth, listened, scraped and scraped.

The line in the middle just means I took a break in annotating and also restarted reading from the beginning.

tailgate

The episode opens by describing Leopold’s interest in eating organ meat: “Mr Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls. He liked thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, liverslices fried with crustcrumbs, fried hencods’ roes. Most of all he liked grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine.” I go to a tailgate for most Eagles’ home games and the guy who cooks for them is a savant at cooking things in a parking lot for a crowd (I once ate pressed duck there) and I wondered if he’s ever cooked kidneys.

Lucia Joyce

Leopold and Molly Bloom have a daughter named Milly, who writes letters to both of them here. She is newly 15 and away working as a photo studio assistant. She has a burgeoning sexuality that Leopold is a little worried about, but also knows he can’t control (this is directly connected to his wife’s sexuality he can’t control). I haven’t gotten very far into my Joyce biography, but I know he had a daughter who had an affair with Samuel Beckett. She would have been 15 when Ulysses was published.

abject/bodily fluid, newspaper; Jasper Johns

At the end of this episode, Leopold goes to the bathroom and has a bowel movement and we’re given quite a lot of detail about the sensations he is having in his stomach at the time. Given that the episode opens with a narrative voice commenting on Leopold’s dietary preferences for organs, we’re getting a mirrored process here: his organs working to complete the cycle.

So I just noted the abject, in reference to Julia Kristeva’s work, which I first read in the context of Jasper Johns’ work in a modern art history class. The abject can refer to things that are of us, but shed from us and elicit a reaction of disgust: vomit, shit, a corpse, wounds. “Our reaction (horror, vomit) to a threatened breakdown in meaning caused by the loss of the distinction between subject and object or between self and other. The primary example is the corpse (which traumatically reminds us of our own materiality); however, other items can elicit the same reaction: the open wound, shit, sewage, even a particularly immoral crime (e.g. Auschwitz).”8 These materials confuse us because they are of us (subjective), but we want to distinguish them as other and remove them from ourselves (objectifying them).

Leopold takes a newspaper with him to the outhouse and uses it to clean himself. Newspaper is one context that Kristeva’s theory relates to Jasper Johns. Johns was involved in the abstract expressionist and pop art movements and one medium he often used was encaustic (painting with wax) over newspaper print. The wax would be built up with colors, but you can frequently see the newspaper below it. In Target with Four Faces (1955) the body is cut up and repeated and frames a target, an object of no narrative meaning other than “focus on this,” perhaps the ultimate objectifying. The newspaper as medium only furthers this friction between body and object.

Newspaper is a symbol of the abject because it is something we (at least the we of the 20th century) consume daily and throw away daily. But Leopold’s trip to the bathroom makes the connection even more explicit by having the newspaper read and then soiled and then disposed of.

My last note on the Post-It just references my surprise at my surprise that Joyce would write someone going to the bathroom in his book.

I also do in-line notations. Some of these are my own thoughts and some come from the Don Gifford annotations, which I have been keeping open next to me as I read.

I’m just noting that Leopold compares himself to a tower, in the eyes of his cat (cute) and Stephen lives in a tower.

I spend conservatively two hours a week looking for me keys. So on first read through, I just laughed at recognition of Leopold leaving his keys in another pair of pants. On second go around, I remembered that Stephen has also left his home without a key. This relates to my unexplained note from my Post-it “Leopold leaves then comes back” because I was wondering if he leaves without the key the second time too.

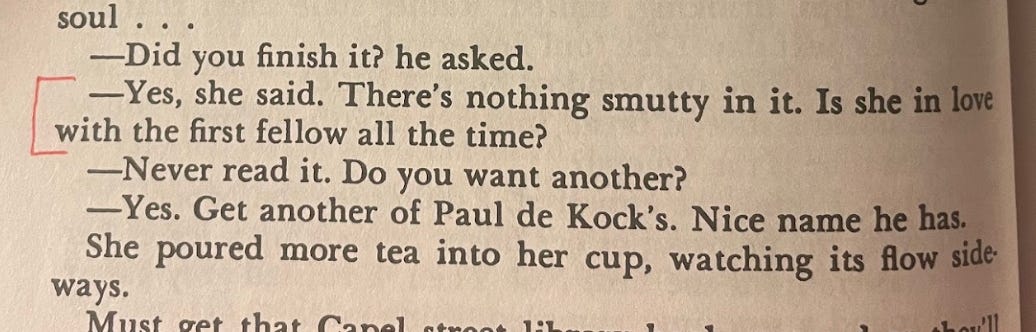

Obviously noted when Molly Bloom is disappointed her pulpy romance novel isn’t particularly smutty.

When Leopold gets the letter from Milly, he sees the address is from Mullingar, where she lives. This is also where Niall Horan is from. I don’t know exactly what I hope to note with this annotation, but my impulse to write it was immediate.

Identifying Leopold’s conflation of his anxiety about his daughter’s sexuality and his wife’s, neither of which he gets a whole lot of say in.

I wish I had written this in the margin so my handwriting was neater, but one of my favorite parts of Joyce’s biography is that he is an Italian voyeur, like myself and Cecil Vyse (hence the daughter named Lucia and son named Giorgio). This particular reference in Italian refers to a song that Molly is going to sing, Là ci darem la mano from Don Giovanni by Mozart, though Leopold is misremembering the line, which is actually “Vorrei e non vorrei,” “I would like to and I would not like to,” which is ingenue Zerlina’s response to the rakish Don Giovanni as he starts to seduce her.

Leopold makes it more complicated by changing the first verb. Obviously “vorrei e non vorrei” is easier to remember and makes more sense as a lyric. He also wonders if Molly will be able to pronounce “voglio” correctly, which is of course moot because it isn’t the right word. Not noted in Gifford’s annotations though is that “voglio” is part of an idiom in Italian that expresses love. “Te voglio bene” is most often used as unconditional, but non-romantic, non-sexual love, as opposed to “Ti amo.” You may recognize it as what Vito Corleone says to baby Michael in The Godfather, Part II.9 Leopold’s wondering at Molly’s ability to say it might speak to his anxiety about her relationship to him, particularly as a matriarch, given the context of them both receiving letters from their daughter, and Molly, in the same delivery, receiving a letter from a man with whom she is having an affair.

recommendations

Brandon’s essay about his current style of annotation, along with the comments where people discuss their style of annotation, in part inspired this exercise.

I use these Muji pens for most of my writing, notetaking. Except for times I go to my Italian class and forget a pen, in which case I use the terrible branded ones that they provide.

My favorite smell in the world is chopped celery, but my second favorite smell in the world is black and blue ink from like a Bic pen. This perfume, Lampblack, is the closest perfume I have smelled to that sensation. It is very bracing, described here as “leather, minus the animal note,” which might put it in the abject category. The skin of the body without the body.

Sherry Thomas and Beverly Jenkins are two romance authors who allow gross things to happen in their books. Ravishing the Heiress by Thomas has a taxidermy dormouse play an important role in the couple’s relationship and her His at Night is one of the only books I can remember someone vomiting and it not relating to a tell-tale pregnancy symptom. Indigo by Jenkins has characters go to the bathroom and a character’s space is vandalized by someone smearing excrement on it.

Some movie recommendations that deal with the discarded ephemera, to very different ends: Sunset Boulevard (1950, dir. Billy Wilder), Don’t Look Now (1973, dir. Nicholas Roeg), A Private Function (1984, dir. Malcolm Mowbray)

Kneecap (2024, dir. Rich Peppiatt): This is going to be on my best-of list coming out after the New Year, but I was unexpectedly charmed by this movie my sister dragged me to. So much so, that we got tickets to see Kneecap in Philadelphia immediately after we got out of the movie and it was the second-best concert I went to all year (after seeing Niall Horan in Dublin). Big year for Irish lads and me.

You can’t put a footnote in a title (this annoys me greatly). But the title of this post is a quotation from Molly Bloom. She is reading a book and comes across the word “metempsychosis” and asks Leopold what it means (“Who’s he when he’s at home?” Very charming). Leopold answers “It’s Greek: from the Greek. That means the transmigration of souls.” She responds “O, rocks! Tell us in plain words.”

This was a specific problem for War and Peace and it turns out Ulysses too because there isn’t a Norton Critical Edition of either. War and Peace because an annotated edition of it would make it impossible to carry and Ulysses may have something to do with the different versions of the text.

Papermate Flair pens changed where they manufactured in 2004. I hate the new ones, viscerally, because they don’t look like the ones my mom used to grade papers all through the 1990s.

I would like to say that I “book briefed” in law school but the only way I could take notes was one running Google doc per class. So I always briefed in a word document. I did hand write all my outlines.

Both episode 1 and episode 4 take place between 8:00am and 8:45am. We know this because Stephen and Leopold hear the same bells to end the chapters.

I’m continuing to call him Leopold instead of “Bloom” because I’m calling Stephen “Stephen” instead of Dedalus because I always want to spell it Dedelus.

This cloud also passes over Stephen in episode 1.

Definition from this wonderfully vintage internet Critical Theory website.

Really, Vito says “Michael, tuo padre ti vuole bene assai... bene assai.” The verb is different because he is speaking in the third person, but it is the same idiom.

This scene where Leopold uses the bathroom calls to mind a Jewish blessing one says after going to the bathroom - Asher Yatzar. It’s one of my favorites because it seems so practical - to be mindful of such complex systems in your body.

I loved Brandon’s essay about taking notes. I do use tabs but I don’t color code, I simply use them to mark important or interesting passages.

The Zionism stuff comes back in a big way in (I think) "Cyclops"—which I've been thinking about for practically the whole year (I read Ulysses in January)—so I'm excited for you to get there.