non-romance, romance, #13: The Lion in Winter (1968, dir. Anthony Harvey)

'tis the damn season

It’s my birthday week! I’m turning 33, the age Jesus was when he died and the age Taylor Swift was when the Eras tour started.

The historical marriage at the center of The Lion in Winter is not considered romantic at large, even when the Plantagenets’ history is ripe for romanticization. Most depictions of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine focus on the embitterment associated with their coupling. The Angevin king did have affairs and his consort did support a revolt against her husband in 1173. This revolt led Henry to imprison her for the last sixteen years of his life. Still, Eleanor was frequently brought out for state business, including the management of the unruly Plantagenet sons’ loyalties (a few of whom helped her with the revolt).

Henry may be cast as a lover, but it is usually with Rosamond, the mistress in the affair that is seen as the irrevocable breaking point in the marriage, like in quite a few operas about this moment. He also might shown as petulant and impulsive, like in Becket, the 1964 film based on a 1959 play by Jean Anouilh, dealing with his friendship with and then murder of Thomas Becket. Eleanor can be the discontented shrew of a wife, but she can also be the benevolent and beloved Regent if the depiction is particularly focused on and favorable to Richard I, her favorite son. This is true in many Robin Hood stories, where John, Henry’s favorite son, plays the villain.

I’m not particularly concerned with the historical Plantagenets here, other than the sense that these personalities are from a vague history. It is important that these things happened a long time ago and it is important that they happened in the medieval period. Because they are medieval, and high medieval at that, the history’s story is linked irrevocably to how this period told stories and what values they put into those stories.

Eleanor of Aquitaine brought the concept of courtly love from courts in Aquitaine first to France and then to England, helping create the genre of chivalric romances. Where would we be today without this etymological ancestor of “romance?” There’s a lot of insistence that genre fiction romance is separate from these medieval romances, but there is overlap here. These chivalric stories’ setting lends itself to time slippage, where things happen suddenly and death for a character is, at best, a temporary problem because they could always show up in another romance. Sir Gawain cheats death by accepting the invitation to the game with the Green Knight and romance characters cheat death by having their stories end at Happily Ever After.1 In The Lion in the Winter, Henry and Eleanor are always playing a game and, I would argue, get a happily ever after.

The contemporaneous history of this squabbling family is colored by legend and literature and a clerical distaste for perceived immorality. Given the constantly shifting allegiances between Henry, Richard and John, it can be unclear what stories are propaganda, written to inflate the current monarch or what is reactionary commentary. No matter the historical truth, the minutiae of these people, like the loaded glances, the biting insults, or the words of affection, are lost to us, just given the distance from where we sit, looking back. I realized and lamented my desire for this first-hand knowledge of the subtleties of history when I read Possession by A.S. Byatt earlier this year, which involves characters taking primary documents and piecing together a relationship and a time jump that shows the reader, but not the characters, where they got it right and where they got it wrong.

The Tortured Poets Department

Pretty quickly into AS Byatt’s Possession: A Romance, I could see why someone might not like it, though all of those imagined annoyances were reasons I was having a great time. The reputation of the Booker Prize Winner from 1990 based on contemporaneous reviews seems to be “hit among critics, slog about readers.” All I can say on that matter is that it …

The Lion in the Winter fills the gaps of history to the brim with dialogue, quick pivots in loyalties, and an ache for something lost. The Christmas court of 1183 at Chinon flatly did not happen, but time moves in mysterious ways in a medieval set romance. And despite the cheating, the plotting, and the cruelty, it is a romance.

the players

The film opens with Henry inviting his three sons and wife to Chinon.2 King Philip of France will be there too, ostensibly to make Henry make good on a long-ago promise of marriage between Richard, the eldest son, and Alais, Philip’s sister. But Henry has taken Alais as a mistress and now wants his preferred son, John, to marry her. Henry is maneuvering John to be the heir and he will need the alliance with France that marriage to Alais provides. John is at court with Henry already, and Richard and Geoffrey are recalled from their respective military maneuvers. Richard is shown to be an active knight, dueling another man, whereas Geoffrey is a tactician, watching a battle from a cliff.

Eleanor is brought from her prison in Salisbury Castle in England, where she has been since Henry imprisoned her since she supported a rebellion led by Young Henry (the late former heir), Richard, and Geoffrey. The sons operate in the film as if the court at Chinon could provide a resolution, an ending to the family drama. Richard wants to keep the Aquitaine, his engagement to Alais, which is only meaningful to him in terms of the alliance with France, and his next-in-line position to the crown. Geoffrey wants to be chancellor for whichever brother wins (or king himself if he can manage it). John mostly wants his father to pick him when it matters. Many of Henry and Eleanor’s moves against each other are foiled by the sons’ inability to go along with the plan in the moment/unwillingness to be pawns to the power players. The sons may understand how they are pawns in the game of power, but what they can’t see is that even the power is just one more thing to be exchanged between the married couple. There’s a game happening between them where they are the only participants, linked by their covenant of marriage.

Henry and Eleanor seem to be the only ones who understand all of the stakes at hand, which are somehow smaller than anybody else is treating them (it’s all been done before and will be done again, Chinon cannot possibly provide a singular solution) and larger (the choices they make affect legacy and history, and not just personal power). They are able to grasp these scales because of how aware they are of running out of time to still be players in the game. Henry and Eleanor repeatedly remark on their own aging processes. They are constantly reminding the viewer that they are closer to death than anybody else.

“I'm fifty now. My God, boy, I'm the oldest man I know. I've got a decade on the Pope.” Henry, when Richard points out his aging body.

“I can't. I'd turn to salt” Eleanor, when she considers looking in a looking glass.

“Where’s that mirror? I’m Eleanor and I can look at anything. [Looking at her reflection] My what a lovely girl. How could her king have left her?” Later, after pieces have moved that put Henry on his back foot.

But they both also have access to a potential infinite that the sons and Alais lack.

“You're like the rocks at Stonehenge. Nothing knocks you down.” Alais on Henry

“Let’s deny them all and live forever.” Eleanor, providing an alternative to choosing an heir, that Henry smiles at.

Alais is the player with the least power for most of the film, which she repeatedly points out, but she also has the least to lose, which makes her dangerous (she points this out too). But Alais fails to make an impact because of a misreading of Henry’s stakes. She tells Eleanor that she loves Henry for Henry as if that makes her love purer than Eleanor’s love for Henry and Henry’s lands. Alais reads as decidedly mortal compared to the goddess-cum-queen-cum-Amazon of Eleanor of Aquitaine. This characterization is aided by the casting of Katharine Hepburn, who is chewing the scenery off the walls in the best possible way here.

The boys squander their chance at rebellion when they all in sequence are revealed to be working with Philip of France in different ways. This betrayal leads to Henry disowning them and desiring an annulment from Eleanor so that he can marry Alais. He has to go to Rome to see the Pope to get the annulment. When Eleanor points out that he’s given them all—the boys, Eleanor and Philip—a common enemy, Henry decides to lock his sons in the dungeon for the duration of the trip. Alais’ big power play comes with she asks Henry not only to keep his children imprisoned in the castle’s dungeon for the length of their trip to Rome but for the rest of their lives. She argues that Richard, Geoffrey, and John would be a danger to herself and any child that she had after Henry’s death.

But this is Alais pushing her misreading of Henry too far: he is himself and his lands, and he is himself and his children. Even when the boys approach him with knives in the dungeon, given to them by Eleanor as a means to escape, Henry cannot bring himself to hurt them. He keels over and says “I couldn’t do it, Eleanor” and Eleanor responds, “nobody thought you could.” There’s a double meaning here: nobody that mattered thought Henry could hurt his sons, and Alais is the “nobody” who thought he might be able to.

the romance

In a part of the screenplay that got cut from the final movie, Alais asks Henry, “When can I believe you?” and he responds “Always; even when I lie.” Henry and Eleanor are full of contradictions in their statements, particularly about their love for each other. The answer to the question “Do Henry and Eleanor love or hate each other?” is “Yes.” Neither has access to a moment of Truth that is removed from machinations, so every expression of affection is a manipulation, but so is every instance of hate. Henry and Eleanor are what they do and what they do is scheme. If love and romance are about meeting your match, only they provide each other the battle that they need in order to keep living. They are playing a game of infinite chess.

Eleanor often talks in terms of “losing” Henry, “giving him up,” or “not having him.” But every time he pivots from calling her “my lady” to insisting that he never loved her, she does have him. Eleanor possesses Henry when he makes decisions centered on her, even when they are designed to oppose her.

Perhaps the most honest moment of Henry’s speeches is when he disowns his sons, a scene that Eleanor is not present for.

My life, when it is written, will read better than it lived. Henry Fitz-Empress, first Plantagenet, a King at twenty-one, the ablest soldier of an able time. He led men well, he cared for justice when he could and ruled, for thirty years, a state as great as Charlemagne's. He married out of love a woman out of legend. Not in Rome or Alexandria or Camelot has there been such a Queen. She bore him many children -- but no sons. King Henry had no sons.

This is before Henry gets it into his head to go to Rome for an annulment, but in this moment of clarity, he connects Eleanor to the larger-than-life vocabulary he usually retains only for himself. Alais may be an “old man’s last attachment,” but someone who only loved him as Henry, not Henry + the lands + power could never match him.

After Henry lets his sons go from the dungeon, unable to kill them, he dismisses Alais to be alone with Eleanor and they discuss what they have wrought on each other.

Henry: I've been cheated, not you. I'm the one with nothing.

Eleanor: Lost your life's work, have you? Provinces are nothing. Land is dirt. I've lost you and I can't ever have you back again. You haven't suffered. I could take defeats like yours and laugh. I've done it. If you’re broken, it’s because you’re brittle. You are all that I have ever loved. Christ, you don't know what nothing is. I want to die.

Henry: Eleanor.

Eleanor: I want to die.

Henry: I'll hold you.

Eleanor: I want to die.

Henry: You will, you know, someday. Just wait long enough and it’ll happen.

Eleanor: So it will.

…

Eleanor: There’s everything in life, but hope.

Henry: We’re both alive. And for all I know, that’s what hope is.3

The couple that has been so obsessed with their age and their limited time and their legacy, finally embraces, done with the machinations for now, and declares hope in their two being alive right now, together. For all the cruelty and barbs and “not having” each other, they end this power-hungry evening in each other’s arms.

the happily ever after

A lot of what I have written this year has been about pushing against the definition of romance—starting to do this series regularly has been a major part of that.4 If the defining feature of a romance is a “happily ever after,” what does that mean? It’s a term of art, it should be defined. If we mean “the lovers are together,” why not just say that? We could define it the way Romance Writers of America does (“An Emotionally Satisfying and Optimistic Ending: In a romance, the lovers who risk and struggle for each other and their relationship are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love”), but I think this definition is flat out poorly written. I don’t think “emotionally satisfying” and “optimistic ending” are defined by “rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love.” It feels like RWA is Trojan-horsing new elements into what makes a romance in the HEA section of their definition.5

At the end of The Lion in Winter, Henry puts Eleanor back on her little medieval barge and sends her back to Salisbury Castle, where she will be incarcerated until he dies in 1189. A husband reincarcerating his wife is not the stuff of a typical genre fiction romance. But to me, what Henry and Eleanor shout at each other from bank to boat are among the most romantic lines in a film ever.

Henry: Come the resurrection, you can strike me down again.

Eleanor: Perhaps next time, I'll do it.

Henry: And perhaps you won't. [he helps her on the boat]

Henry, as Eleanor is sailing way: You know, I hope we never die!

Eleanor: So do I.

Henry: You think there's any chance of it? [They both earnestly laugh]

For the whole movie, Henry and Eleanor have brought focus to their mortality, privately and publicly reminding us that they are on a time crunch. But then, with a mention of Easter and the theme of resurrection, we get this open-ended possibility that aligns with the king and queen’s actual attitudes in their negotiations: this could go on forever and they would be satisfied. For all the chess moves that take place during the Court at Chinon, there’s no “solution” provided at the end of the film. Richard, Geoffrey, and John still don’t know who will be the heir. But Henry and Eleanor have played the game before, and they hope to play it forever. This satisfaction is in the game narrowly written to their relationship; the other players aren’t playing the right game, or the same game. Henry and Eleanor are inextricably linked together, by their exchange of lands and creation of sons, but also by virtue of their marriage. (“You’re still a marvel of a man.” “And you’re my lady.”)

That union is threatened substantially twice, first when Henry pledges affection and loyalty to Alais in front of Eleanor in a chapel, performing a simulacrum marriage ceremony, and when he threatens to go to Rome to get his marriage annulled so that he might actually marry Alais. But their lands and power, which should be seen as a part of themselves, are so tangled up together that in these moments when Henry wrenches against them, he begins to break. He exists above his sons, as the current king, and he exists above Alais because he is married to Eleanor. They are on a plane of two that no one else can access.6

To me, those lines exchanged between Henry and Eleanor are absolutely a happily ever after. This couple, still a couple since they are married to each other and because nobody else could meet them where they are, will continue into the infinite and be satisfied and happy with that. The medieval Henry and Eleanor of history die, but the medieval Henry and Eleanor of romance go on forever.

recommendations

A Proud Taste of Scarlet and Miniver by EL Konisburg: A very strange and wonderful chapter book for children! Eleanor of Aquitaine is sitting in heaven, waiting for Henry to show up. He died first but sinned more in life, so was given more time in purgatory than she was. She, along with Abbot Suger, Empress Matilda and William Marshall, recollect her life, including her marriage to Henry on the day he is supposed to arrive in heaven. That this story is even available to someone’s imagination (published in 1973, so five years after The Lion in Winter was released) is proof that there is something attractively infinite about this couple.

One Night is Never Enough by Anne Mallory: My favorite Regency Romance where games, including chess, are played.

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens: I do mean the literal text, rather than an adaptation. You can probably finish the whole thing in two hours, or read it aloud in four. I’ve never seen an adaptation that is as fun as the original thing and I’m always so happy to revisit it every year. This year I listened to the audiobook version narrated by Jason Isaacs, which is on Spotify.

“The Night of the Magi” by Leo Rosten: My dad read this story aloud to me most Christmases. Rosten was a New York, Jewish humor writer. My dad is from Pittsburgh and is as Calvinist in his disposition as they come, but he does love funny things and Rosten is very funny. This story makes me belly laugh and cry every year!

Stalag 17 (1953, dir. Billy Wilder): I’m not sure exactly how this movie became a Christmas tradition for my family. Like many Wilder movies, it feels about 20 minutes too long and I remember all the kids struggling to stay awake whenever we’d watch it on Christmas Eve. But this prisoner-of-war comedy that turns into a thriller in the third act does take place around Christmas time (the darkest nights are the ones best for escaping German prison camps). My sister once asked me what movie most influenced how I speak and it is probably this one. I find myself quoting it constantly, even if most people around me have never seen it.

A Christmas Gone Perfectly Wrong by Cecilia Grant: Christmas novellas are such a weird phenomenon to me in romance. I don’t usually enjoy novellas because surprise! The pacing usually feels off. But Grant, a singular talent, pulls this Blackshears prequel off.

Happy Holidays and Merry Christmas! The next non-Ulysses letter will be my best of 2024 list, coming out in the New Year.

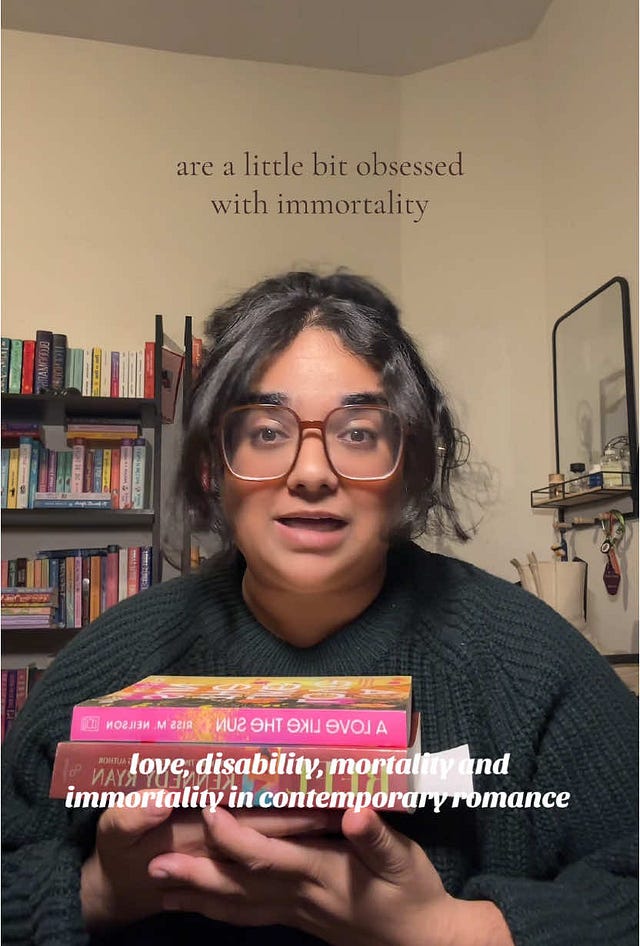

Great video about this concept of romance’s obsession with immortality but in the context of disability in romance, from Sanjana

During Henry’s reign, most of the Normandy coast was a part of the Angevin empire, along with the west of France with Eleanor’s holding of the Aquitaine. The historical king was much as French in our modern eyes as he was English, so he had a Christmas court at a French castle.

In the original screenplay, the line is “We have each other and for all I know, that’s what hope is.”

Hint at the first big project at Restorative Romance for 2025

Again more on this soon!! Though I am still working on it, I suspect my definition of romance has to have an element of relativism for the couple that we spend so much time on in the romance. Wuthering Heights is a romance because haunting the moors in the afterlife is the happily ever after for Cathy and Heathcliff, though being buried together on a slope with moss creeping up the headstones is not a happily ever after for most characters. I also think authorship can be a relative element here. I opened my newsletter over two years ago with a look at how in order for Lisa Kleypas to secure a happily ever after, the house at the center of the story has to be restored.

The “elevation” of Henry and Eleanor becomes particularly clear if you also watch Robin and Marian, starring Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn, directed by Richard Lester from 1976. It was also written by James Goldman. Robin and Marian are not married and not royal. They are also obsessed with their aging, given that they have separated for decades in this story, but how they deal with is very different.