On my 3 x 5 sticky note for episode 6 of Ulysses “Hades,” I wrote “going into hell—Dante ↑ Aeneas?”1 before I ever started the episode in earnest. I was just reading the Gifford annotations’ summary of the corresponding Odyssey incident, where Odysseus, on advice from Circe, enters hell and sees friends and family in the afterlife. This parallel reminded me that I had meant to look up what Joyce’s relationship to Dante was based on early noticing of references to The Divine Comedy.2

In this episode, Leopold Bloom’s own hellish journey is in a carriage ride through Dublin in a funeral procession for Paddy Digman, along with three other men. The funeral at 11:00AM has been the fulcrum appointment for the first six episodes, with pretty consistent references to it to situate the setting in the time of day. The Odyssey correspondences are heavy here, just like last episode, with many one-to-one parallels, including the carriage making four crossings over water, to match the four rivers of hell, a sympathetic Sisyphus in a husband who perpetually refurnishes his house after his alcoholic wife pawns the furniture every week, and a king of the underworld (graveyard caretaker) married to a fertility goddess (a particularly fecund Irish wife). “Circe” as a catalyst for a hellish journey will come back, out of order from The Odyssey, in a big way for episode 15. Richard Ellmann suggest that Hades has to come first because of the Irish custom of morning funerals.

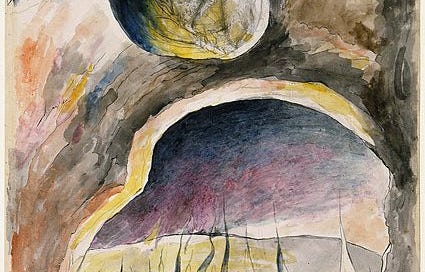

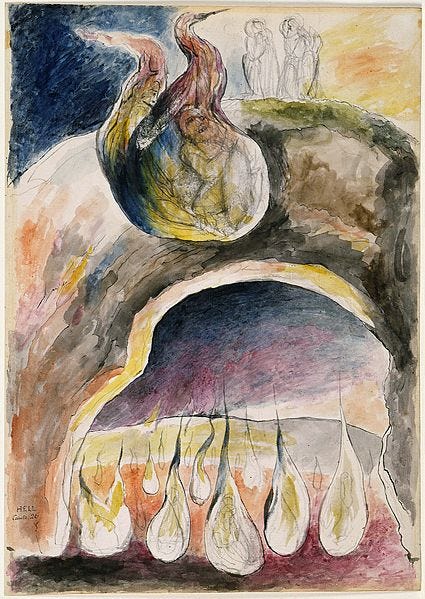

Hamlet and The Odyssey are Joyce’s main fonts of structure. But Dante is here (Dante is everywhere); I can feel him in a story about men who are political and philosophical exiles, who go on journeys full of “Dublin street furniture,”3 the term Don Gifford uses to describe all the highly specific references to people and places of real life Dublin. Dante’s afterlife could easily be described as populated with “Florentine street furniture.” Leopold Bloom is 38 in the book and Joyce was 32 when he started the novel, certainly both in the “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita” period of their respective lives that opens Dante’s epic, when he is 35.

Joyce’s relationship with Italy and the Italian language, that I am learning about from his biography by Ellmann, suggested to me that would be a thread worth pulling, despite Dante references not makes a huge scene in most of the glosses that I am reading so far, though they are consistently present. I did check an electronic edition of the Gifford’s annotations and it seems like the Dante references are going to get more heavy starting next episode, but given Leopold’s descent into Hades this one, I was interested in learning more about Joyce’s relationship to il Sommo Poeta and taking more of Dante with me as I continue reading.

In her first chapter of Joyce and Dante: The Shaping Imagination, Mary T. Reynolds writes “as Joyce’s art developed and matured, his imitations of Dante submerged into the fabric of his fiction. This process was less a matter of deliberate concealment…than of Joyce’s making more and more fully his own the artistic devices and maneuvers he found in Dante’s poetry.” So Dante doesn’t make it into a column on the explanatory schemas provided by Joyce of his work, but exists as a deep part of the author writing the book.

It’s always nice when Ulysses commentaries reflect back my experience to me—one reason to read a classic book is to have the same experience as other people who have read the classic book. Just like I was calmed to learn that “Proteus” is the episode where a lot of people give up, many of the glosses and annotations I read for this episode notes acknowledged that “Hades” works easily enough as a short story out of Dubliners. It would be hard to miss the plot of this episode—the funeral procession, funeral itself and social reception that follows. Though more obscure, it’s still pretty easy to parse Leopold’s social situation as an outsider amongst even his social group, to read the awkwardness of these men in mourning, and see Leopold’s quirky (and mourning) mind working as his considers burial rites, both personally and societally. And those one-on-one parallels to The Odyssey announce themselves quite loudly, even without relying on an annotation guide.

What was harder to me to figure out was how to hold the weight of this episode relative to what proceeded it. I’m now at the end of Leopold’s three chapter introductory cycle, which runs parallel to Stephen’s three chapter cycle. This episode is where Leopold sees Stephen for the first time, pointed out as he and his fellow mourners are in the carriage, to Simon Dedalus, Stephen’s father. Each of Stephen’s opening chapters is paralleled and completed by Leopold’s in some way. Going forward, the heroes will not necessarily be together, but be moving in the same direction, at the very least.

The most robust discussion of this structure question that I’ve read comes from Ellmann’s Ulysses on the Liffey, published on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the book. In his chapter 6, “The Circle Joined,” Ellman writes: “Each of the first three chapters is half a circle, to be completed by its parallel chapter in the second triad. Mulligan's transubstantiation of God into flesh in Telemachus is completed by Bloom's transubstantiation of flesh into faeces (Calypso). The sadism of Christians and Romans persecuting Jews (Nestor) is completed by the masochism of Christians and Buddhists in their devotions (Lotus-Eaters). In the Proteus episode Stephen follows the arc of generation through corruption to death, while in Hades Bloom begins with death and follows it back to birth.”

But Hades (episode 6) isn’t just a parallel to Proteus (episode 3), where Stephen considers death and drowning and the mourning of his mother head-on, at the same time that his father is crying about his wife at another person’s funeral and Leopold is thinking about Catholic funeral rites as a spectator. This episode is also bookend to Telemachus (episode 1). Stephen in a social setting with Buck Mulligan and Haines, electing to start his exile rather than stay in his usurped tower mirrors Leopold’s otherness and awkwardness with the three men who are his friends, but who all call him by his last name, while addressing each other with their given names.

These interlocking circles of a story of a man at 22 and a man at 38 are representative of Joyce at the age when he exiled himself from Ireland to Trieste and immersed himself in Italian and European thought, rereading Dante as an adoptive Italian, and the age he might have been when he finished the work (it was actually published when he was 40), but firmly middle aged. In their Dantean journeys, Stephen is in the period leading up to the opening of the Inferno, and Leopold is there, prepared for his descent and return (just like Odysseus). The metaphor of interlocking half circles can easily shifted into circling concentric circles.

I considered saving my deep notes on Dante for a later episode’s update—the “Aeolus” episode (the next one) has a direct reference to Francesca and Paolo in The Inferno that I spoiled for myself and the parallel inferno, purgatory, paradise that I buy the most starts not in “Hades,” but in the “Circe” episode (from Carole Slade’s “The Dantean Journey in Dublin,” 1976). But the question I kept seeing repeated in works about Dante and Joyce was along the lines of “what exactly do we do with these parallels, that are clearly there, but that Joyce does not announce at the level of The Odyssey and Hamlet?” This question felt like my own matching half-circle of “what do I do with the Hades episode, where I understand more easily the what than any other passage, but are more lost on the why than ever?”

Mary T. Reynolds writes, “It is easy enough to find traces of Dante in Joyce's work; the difficulty comes when one tries to fit them into a pattern.” Everything I’ve read about Dante and Joyce quotes Joyce twice from two periods of his life. First, a quotation from his youth, “I love Dante almost as much as the Bible. He is my spiritual food…,” but then later he says “Dante tires one quickly; it is like looking at the sun.4 The most beautiful, most human traits are contained in The Odyssey.” This change in attitude, if you can call it change, maybe a shift, suggests something lacking in Dante found more perfectly in The Odyssey. But the prevalence of surface level references to The Divine Comedy means that Joyce can’t abandon the poet completely.

Unlike The Odyssey itself, which I have been reading in parallel with Ulysses, when so inspired, the references to Dante are scattershot and I’m not sure I’m ready to take on a reread of the whole The Inferno and read Purgatorio and Paradiso for the first time, while in the middle of this big read. But I can take on rereading Canto 26 of the Inferno, where Dante’s Ulysses appears.

The Ulysses of Dante and the Odysseus of Homer are contrasting characters, since Dante borrows the characterization of the wily man from mostly, who else, Virgil and his Aeneid. Though, according to the notes on Digital Dante, Dante also looked and invoked Horace much more sympathetic portrayal of the hero. Odysseus in The Odyssey is a hero, sympathetic in his ill-begotten journey home, humorous in his ability to outsmart those working against him, destined to achieve the perfected nostos. Virgil’s Ulixes is “dreadful” and “accursed.” Ovid in Ars Poetica focuses on the fight between Ulysses and Ajax for Achilles armor—Odysseus sees Ajax in Hades when he ventures there in The Odyssey. Ajax rebuffs him, paralleled in Ulysses when John Henry Menton, who Leopold once bested in lawn bowling, is rude to him, motivated by the dispute and his antisemitism.

WB Stanford, in his book The Ulysses Theme, distinguishes between Homer’s Odysseus as a centripetal figure, moving toward a center (his home), fulfilling that Greek virtue of nostos, and Dante’s Ulysses, as a centrifugal figure, tending towards the outskirts. He borrows these terms as a physical metaphor from Joyce himself, in episode 17, “Ithaca.” When Ulysses tells his story to Dante and Virgil, he relates his time spent with Circe. But he then says

neither my fondness for my son nor pity

for my old father nor the love I owed

Penelope, which would have gladdened her,was able to defeat in me the longing

I had to gain experience of the world

and of the vices and the worth of men.

The thing getting him off the island is knowledge, not home. He sails outward to the edges of the southern hemisphere and comes upon Mount Purgatory, overwhelmed by the scale of the mountain and the stars above. This links Ulysses, sympathetically, with both Dante through the location of the journey and Adam, through the act of trespass.

While I think I know that Leopold Bloom will ultimately be a centripetal hero, returning home after wandering, the question of outward or inward movement is still outstanding in the narrative. Stanford points on that Joyce’s heightened emphasis on the Telemachus figure (Stephen Dedalus) helps manage the tension held in a Ulysses whose history has both impulses. Stephen is on his way to reject that which is behind him and Leopold is working his way back. In the next episode, I know they don’t meet yet, but the narrative recoils back to capture both heroes and their differing narrative values.

I also noted how often Don Giovanni keeps coming back up. He also goes to hell!

I’m thinking of how much of Florentine politics we know because Dante tells us about it, pettily and poetically.

The first reference to Dante that I recognized in Ulysses came in episode 3, Proteus, when Stephen thinks of Guido Calvacanti, Dante’s mentor and friend and an anecdote from The Decameron by Boccaccio. In this moment, Stephen is ruminating on Buck Mulligan’s mockery of him, and his masculinity. One day, a group of courtiers, who resent intellectual (and atheist) Guido for not joining their social ranks, mocks him, asking “Guido, you refuse to be of our company; but behold, when you have found that God does not exist, what will you have done?" as they encircle him a graveyard in between Orsanmichele and the Baptistery of St John (if you do this 300m walk now, you’ll pass a Zara). Guido, with all his wit, retorts “Gentlemen, you can tell me in your house what you like” and hurdles himself over a grave to escape the taunting. One of the mockers explains to the others: “If you will look carefully, these tombs are the houses of the dead, because in them the dead are placed and dwell; which he says are our home, to show us that we and other idiotic and uneducated men are, in comparison with him and other learned men, worse than dead men, and for this reason, being here, we are at home."

Stephen is fantasizing about being able to respond to his opps (“But the courtiers who mocked Guido in Or San Michele were in their own house. House of …”), but instead interrupts himself with an imagined comment from Buck Mulligan: “We don’t want any of your medieval abstrusioities.”

“My father”—[George] looked up at [Lucy] (and he was a little flushed)—“says that there is only one perfect view—the view of the sky straight over our heads, and that all these views on earth are but bungled copies of it.”

“I expect your father has been reading Dante,” said Cecil, fingering the novel, which alone permitted him to lead the conversation.

From A Room with a View, by EM Forster