non-romance, romance, #14: Love Story (1970, dir. Arthur Hiller)

that's what it's about, preppie

This is a non-romance, romance, a monthly subscription feature where I write about something other than strictly romance novels through the lens of romance. They are some of my favorite things to write.

Unlike many of the stories that I choose for non-romance, romance, Love Story (1970) disqualifies itself as a romance novel on its face, immediately. The opening line is: “What can you say about a twenty-five-year-old girl who died? That she was beautiful and brilliant? That she loved Mozart and Bach, the Beatles, and me?”

I can stretch Summertime (1955, David Lean) into a romance because it’s as much a love story between Jane Hudson and Venice as between her and her married Italian lover. Neither set of lovers is “together” at the end of the movie, but I don’t know how someone watches it and thinks that Jane experiences anything other than a happily-ever-after, made available by her love affair, with both man and city. And The Lion in Winter (1968, Anthony Harvey) gives me an out to call the cantankerous, bitter marriage of Eleanor and Henry a romance because they triumphally remain married, in their own singular way, at the end of the movie. Even in Wuthering Heights or Titanic, we get either the metaphorical sense or literal depiction of an ever-after afterlife for the deceased couple.

But Jennifer Cavilleri (Ali MacGraw) will die; we know this from the opening swells of the Love Story theme, accompanied by Oliver Barrett IV’s (Ryan O’Neal) voiceover where he is at a loss for words when he tries to tell us about his late wife. It’s like the prologue of Romeo and Juliet1—“we’re telling you what is going to happen, don’t get mad when she dies.”

The story is pretty simple: wealthy boy meets working-class girl and she gives him a hard time when he tries to pick her up. He gives up his big man on campus ways to romance her and they fall in love, romancing in great clothes on Harvard’s campus. They marry against his parents’ wishes and the couple struggles to put him through law school. They have exactly one fight and it leads to her saying the tagline of the film: “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.” Boy succeeds greatly in law school and gets a job as an associate in Manhattan. Once they are justly rewarded with an ascendence to the middle class, the girl gets a terminal diagnosis. She fades away very quickly and the boy is devastated. (A more detailed plot summary is in the footnote if you’ve never seen the film.2)

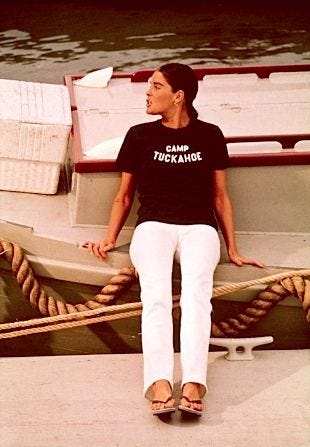

The cultural impact of Love Story is hard to overstate. Erich Segal, a Yale classics professor who occasionally wrote for Hollywood, shopped around a screenplay, initially with no takers. But Ali MacGraw, model-turned-actress and new wife to Robert Evans, head of Paramount, happened upon the script. At the end of 1969, the script was moved to production, with MacGraw attached, and it was decided that Segal would adapt his screenplay into a novel to serve as promotional material for the film, a fairly new method of promoting movies.

On February 14, 1970, the book became an instant bestseller. Before the movie even came out, 1 million hardcovers and 4.3 million paperback copies were sold. The book would eventually sell 21 million copies and spend nearly a year as the New York Times #1 Best Selling Fiction title. The name “Jennifer” became the top name for girls for 14 years after the publication of the novel. “Oliver” did not experience the same immediate and sustained popularity bump, but “Ryan” did, first experiencing a boost coinciding with Ryan O’Neal’s appearance on Peyton Place and then more gains with the release of Love Story the film. A 1971 Gallup poll found that one in five Americans had read Love Story.

If possible, the film, made with just a two million dollar budget, was an even bigger hit. With its box office adjusted for inflation, it made $772,362,657 in 2020 dollars, ranking in the top 50 highest grosses of all time.

I think it is foolish to think that Love Story has no relationship to romance as a genre, even if Jenny dying at the end crosses your HEA hardline and you’ll never call it a romance. Marketing of the film certainly framed the story as romantic. And genre fiction romance experienced a huge boom in the early 1970s, not because of Love Story directly, but because participants and catalysts of that boom certainly read and watched this story. I think there’s even a connection to historical romance, if we look at how Love Story was discussed at the time of its release and the ethos of the film.

I’ll discuss all of this in this sprawling essay, but I am going to start with how we talk about Love Story now. Because like genre romance in general, there’s a flattening that happens when we’re looking back at something, with the assumption that we must be smarter than all those people (in many cases: boomer women) who supposedly earnestly loved this thing, whether that thing is Love Story or a Woodiwiss bodice ripper. I think these discussions will remind romance readers of much of our cyclical discourse defending the genre.

For all of the splash Love Story made in 1970 and 1971, by 1972, we already have Ryan O’Neal participating in lampooning of the film’s most famous line in Peter Bogdanovich’s screwball comedy What’s Up Doc? His character apologizes to Barbra Streisand’s Judy and declares his love. She responds “Love means never having to say you’re sorry” and he deadpans, “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard.” Instead of a swelling orchestral theme, we get a Looney Tunes stinger. The sleeper hit has turned into a punchline.

This distant and derisive irony is generally how I would describe the attitudes around Love Story that I see. Almost everything I read written in retrospect about Love Story qualifies speaking about the film with an acknowledgment that there is something deeply stupid about it, ranging from apologetic to hateful. Even in the New York Times obituary of director Arthur Hiller, there has to be an acknowledgment that “‘Love Story’ offered a strong, simple palliative, turning audiences teary-eyed (though some found it sappy).”

On the hateful extreme of the film's mockery is the Crimson Key screening, held annually at Harvard. The film is set and filmed at Harvard and Radcliffe, and since the late 1970s, the community service organization has held a screening for freshmen at Harvard. At the screening, older members of the group sit in the back and yell communal one-liners at the screen over the heads of the freshmen.

Given my experience of seeing old movies in theaters with crowds, I was not surprised to learn from a 2010 New York Times article, that brought knowledge of the tradition to a wider audience, that Jenny gets the largest proportion of jokes at her expense. The article reports “[h]owls of disgust greet her when, during the blizzard scene, she falls on her back and spreads her arms and legs to make a ‘snow angel.’ And her assertion that her class in ‘Renaissance polyphony’ is ‘nothing sexual’ elicits a chorus of ‘Neither are you!’”

The description of the screenings made it sound like it was a social litmus test for who gets to be ironically detached from the Harvard brand of education. It was illuminating to provide more context to myself about the people who gave quotes to the article. Kermit Roosevelt, class of 1993, told the Times reporter: “It was an aspect of the complicated relationship that people have with the Harvard mystique you want to embrace it, but not too seriously…You want to be ironic about it.” The article does not relate that this Kermit Roosevelt is Kermit Roosevelt III, great-great-grandson of Theodore Roosevelt. So the student who wants to “embrace it, but not too seriously” is about as aligned with Oliver Barnett IV as anyone who has ever lived. Roosevelt doesn’t technically have a building named after his ancestors at Harvard, but the university does have some of Teddy’s archives and a long connection with the family.

This attitude contrasts with that of Raymond Vasvari, class of 1987: “What struck me was the collective uncertainty of what it all meant…You take all these people from different socioeconomic backgrounds who are suddenly stamped with the Harvard imprimatur and marched into this big, brutalist, antiseptic space with 1,600 other geeks to watch this girl die. And you’re sitting around watching people’s reactions to you. I suppose I was supposed to be made effete by the experience. Was Ryan O’Neal supposed to be my role model?” Vasvari is the grandson of union organizers from Youngstown, Ohio.3 Vasvari was not a fan of the film, but he captures the social dynamic of the irony-fueled event that divides those who can take on Harvard as Brand with a wink and who might struggle to detach from their vision of the hallowed halls.

Jenny Lyn Bader, playwright (and step-daughter of Joseph Stein, writer of Fiddler on the Roof) best captures my reaction to reading about these screenings: “There was a feeling that one needed to make fun of Harvard, and be dismissive of human emotion and that we should establish that during Week 1 that too much tenderness would not fly in this cerebral atmosphere. It was mean-spirited.” I’m all for making fun of Harvard, but the gap in Roosevelt and Vasvari’s quotes and backgrounds tells a story that the NYT ignores about the experience of hearing jeers at the idea of Harvard being depicted next to something that asks for and plays with earnest emotion. It’s like the joke of asking someone who went to Harvard where they went to school and they answer “just outside of Boston,” as if claiming the powerful institution directly would be gauche and bourgeois.

If Love Story is anything, it is gauche and bourgeois. The couple's journey to happiness involves achieving middle-class stability without old money support. The tragedy is that they don’t get to live that life together for very long.

Jenny: It was a good apartment for 80 bucks.

Oliver: Now our garage will cost that.

Jenny: Why have a car in New York?

Oliver: House calls, Jenny.

Jenny: Lawyers for Jonas and Marsh don't make house calls.

Oliver: Yes, to Mr Jonas and Mr Marsh.

Jenny: You can walk there.

Oliver: Rich people ride.

Jenny: Nouveau riche people.

Oliver: That’s us.Jenny and Oliver, on leaving their Cambridge apartment for Manhattan

Sometimes the dismissive attitudes lead to a flattened reporting of what is actually in the film. In The Hollywood Book of Love: An Irreverent Guide to the Films that Raised Our Romantic Expectations, entertainment writer (who also happens to be an Ivy League educated attorney, like Oliver) James Robert Parish elides the first line of the film to make it seem more shallow than it is. “As you sniffle through this feature, bear in mind that these characters give shallowness new meaning…[O]ur clean-cut hero asks over the soundtrack mournfully ‘What can you say about a twenty-five-year-old girl who died?’ His brilliant reply includes that she was beautiful (certainly a matter of personal taste4) and that ‘she loved Mozart and Bach . . . and the Beatles.’ That’s the best he can come up with? Oh, brother!”

Parrish excises two bits of the quotations that don’t suddenly make it Shakespeare, but do give more depth that he seems willing to acknowledge could possibly exist in Love Story. The line, as I quoted above, is “What can you say about a twenty-five-year-old girl who died? That she was beautiful and brilliant? That she loved Mozart and Bach, the Beatles, and me?” This line is the frame of the film, what Oliver opens with while sitting out looking at an ice skating rink before the flashback of the story starts. The film ends with him walking to that rink again, closing the loop of the frame narrative, immediately after his wife had died.

On Jenny’s deathbed, she quotes Hamlet but gets frustrated that she can’t remember the play the line is from. She reminds Oliver that she once knew all of the Mozart Köchel5 listings. Their romance begins when Oliver is checking out a book from the Radcliffe library and their courtship takes place over their textbooks. A huge part of the love story is that Jenny is incredibly literary and gifted at music! Oliver loves her brilliance and predictably is inspired by her work ethic and sacrifice for him to rise to graduating third in class from Harvard Law School.

After the couple has sex for the first time, they discuss why Jenny left the Catholic Church. She wears a cross for her mother, but her atheism runs throughout the film. She dreamily declares to Oliver “I never thought there was another world better than this one. What could be better than Mozart? Or Bach? Or you?” Oliver, taken aback by her offhand declaration, asks “I’m up there with Bach and Mozart?” Jenny smiles and says “And the Beatles” before she kisses him. Removing “brilliant” and “and me” artificially makes the romance shallower than it is in the film to serve the idea that “this is drivel.” The screenwriting may be trite, but the issues that Parrish lampoons speak more to how the film is remembered than how it is.

The dismissal of the film’s quality or attraction can also be found even in the context of people who are praising aspects of it. In 50 Moments of Fashion that Inspired Romance by Hal Rubenstein, one of the founding editors of InStyle Magazine, the Love Story chapter opens with “Cheaply produced, poorly shot, and badly edited,6 Love Story's plot stumbles along…devoid of pace or grace…then why and how did Love Story leave millions of moviegoers eagerly sobbing hysterically into a puddle of soaked tissues? Made for a mere two million dollars, the film earned fifty times that to become the highest-grossing film of 1971, its tear-stained success due to the rare alignment of brilliant marketing, fortuitous timing, savvy Casting, a reassuring return to overlooked attire, a single rhapsodic production element, and one rapturous plug from a famous fan.”7

The clothes in Love Story are fantastic, and it makes sense that, in this book, Rubenstein would focus on them. But the underlying thesis here is: this movie is stupid and outpunched its weight class by becoming so big, even in a book that glossily reproduces and praises a major aspect of the mise-en-scène (I’ll talk more about the meaning we can derive from Jenny’s clothes in a later section).

The dismissal of this film as obviously unworthy, coupled with the scale of its pop culture moment, recalls so many cycles of takes and discourse about romance, first as something harmful and then as always a moral good. Chels’ latest post at The Loose Cravat explores this cycle more.

I am not aiming to respond reactionarily to these offhand insults to a movie I love. There are problems with it, and it certainly isn’t an aspirational text. I just think something more interesting is going on with Love Story than the saccharine schlock that caused a bunch of Baby Boomers to experience weepy psychosis and begat us a generation of women all named Jennifer.

To unflatten the discussion, I went back to see how the film was discussed in 1970 and 1971, both in reviews and features in newspapers and magazines. Love Story’s big office returns did not correlate with universal acclaim. But contemporary reviews, even negative ones, are certainly more interested in discussing Love Story as a text of art, rather than a cultural artifact.8

The most positive contemporary review I’ve found came from Roger Ebert, originally published in the Chicago Sun-Times. He posits that Love Story should be taken on its own terms, as a sentimental weepie movie. “I would like to consider, however, the implications of ‘Love Story’ as…a movie that wants viewers to cry at the end. Is this an unworthy purpose? Does the movie become unworthy, as Newsweek thought it did, simply because it has been mechanically contrived to tell us a beautiful, tragic tale? I don’t think so. There’s nothing contemptible about being moved to joy by a musical, to terror by a thriller, to excitement by a Western. Why shouldn’t we get a little misty during a story about young lovers separated by death?”9

The most interesting review came from Vincent Canby10 at the New York Times. Canby’s review is biting, while acknowledging a central appeal of the film. Something is clearly working for the millions of people enamored with it. He found the book unreadable but thinks the movie works because “Jenny is not really Jenny but Ali MacGraw, a kind of all-American, Radcliffe madonna figure, and Oliver Barrett 4th is really Ryan O'Neal, an intense, sensitive young man whose handsomeness has a sort of crookedness to it that keeps him from being a threat to male members of the audience. They are both lovely.” Most reviews mention some magic between the lead couple as a compelling factor over the book.

Canby ends his review with “I can't remember any movie of such comparable high-style, kitsch since Leo McCarey's "Love Affair" (1939) and his 1957 remake, "An Affair to Remember." Both of those films’ heroines are disabled by automobile accidents, rather than dead by vague blood disorder. His ironic tone in his review led to letters to the editor about his distaste for the movie, which prompted him to explain a follow-up review, published alongside a more negative one from Richard Corliss, that “there was a good deal of astonished irony in my review, but I meant my admiration to be taken seriously.”

Pauline Kael wrote a scathing review in the New Yorker, with similar issues that Canby had, though she was not charmed by the hollowness of the conflict between father and son. She writes “it is a generation gap variant of a Neo-Victorian heart-wringer in the tradition of ‘Madame X,’ ‘Imitation of Life,” and ‘Magnificent Obsession,’ with maybe a little ‘Dark Victory’ thrown in.”11 Of the book, she says “there can be little doubt it has been read by many people who rarely read anything in hard covers.” She suggests that movies like Ryan’s Daughter by David Lean (another much-maligned movie that I love) and Love Story “take place as if the world were still 1944, but without the war…It deals with private passions at a time when we are exhausted from public defeats.” All of this works to manipulate an audience into weeping so they don’t see the manufactured conflict at every turn.

There is a throwback quality to Love Story to maudlin melodramas of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, especially as a contrast to the other big movies from 1970. There’s no Vietnam draft looming for Oliver,12 there’s no racial tension, no assassination paranoia, no hippies. Oliver’s big rebellion against his WASP father? Marrying a non-practicing Catholic girl, who is charming in every way, going to law school, and graduating third in his class. This style and level of conflict also feels plucked out of a historical novel, where a father disapproves of a working-class girl and the big rebellion comes by rejecting the family fortune and earning a wage.

I love this movie, but I don’t disagree with Kael that the generation gap that proves insurmountable—Oliver walks away from his father at the end of the film—feels utterly manufactured.

Oliver is the “preppie,” associated with the conservative families of his Boston Brahmin family, but Jenny gives us a few major hints about the conservative, throwback ethos of the film. She loves Mozart and Bach, understandable for a music major at Radcliffe, but she also loves the Beatles, who were broken up by the time of the film’s release. Her favorite band at 22 is one that came on the scene when she was 14 or 15. The Beatles are the greatest band of all time, but she pointedly doesn’t list a band that played at Woodstock, or God forbid, Altamont.

Jenny’s other big contribution to the film is her wardrobe. I found it hard to parse what fashion items from the film became associated with the early 1970s because of the film, which are worn in the film because that’s how people dressed in 1969/1970. But like the shadowed absence of Vietnam, or Jimmy Hendrix, what trends Jenny doesn’t wear sets her back to a phantom, nostalgic past, even if it’s just a few years back.

This Life magazine spread of high school students in 1969 shows many trends that would be out of place in Jenny Cavilleri’s wardrobe. Fringe, paisley print, bell bottoms, printed tights. Her clothes are certainly not so out of place in 1970 that they look like a costume, but there’s a lack of experimentation and a mod-ish early 1960s bent to her color palette and silhouettes. She doesn’t wear bellbottoms, she wears pedal pushers. She wears miniskirts in 1970, though Mary Quant who pioneered the look in the early 1960s, released no miniskirts that year, as designers moved on to midi-skirts.13 At least to my 2025 eye, Jenny’s working class is not signaled by her clothes in any meaningful way. Jenny and Oliver’s world in the text of the film does seem like a snowglobe, unaffected by outside factors.

But another Kael quote made me reconsider my stance on Love Story’s snowglobe neutrality, even though I don’t know she would apply it to the film. Kael said in an interview with Mademoiselle in 1972: “Vietnam we experience indirectly in just about every movie we go to. It’s one of the reasons we had so little romance or comedy—because we’re all tied up in knots about that rotten war.” Of the other box office hits from 1970, M*A*S*H has the warfront, albeit the Korean War, and Patton has mercurial, “great” men leading boys into battle, Woodstock has the disaffected youth and Airport has a soldier returned home moved to violence out of economic anxiety. But Love Story has something none of those have, despite Kael seeing its world as 1944 with no war: a close-up of a beautiful and brilliant, just-out-of-college person dying for no logical reason. How could an audience in 1970 see that and not think of a generation lost, often in the years after graduating college and aging out of student deferment. She loved Mozart, Bach, and the Beatles. And Oliver. And I cry every time.

Canby, in his follow-up review of Love Story, responding in part to all those letters to the editor that accused him of hating it the first, acknowledges that this backward nostalgia, devoid of present context, despite being presented as a contemporary film, can be read as a political statement and if a viewer takes it that way, it is a “is a giant step to the right of the right‐wing.” But he also provides an alternative in reading the film like a film from the past. He writes: “If, however, one takes it as a fairy tale, one can accept its distortions, the manner in which it substitutes artificial problems for real ones, and read them for what they say about the condition of the contemporary American fantasy, much as we used to do with so many of the movies that came out of Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s.” I don’t think Canby is saying even that Love Story is escapist. Fairy tales are a site of our anxieties to be processed in world of heightened exaggerated symbolism. They are fantasies, but not fantasies as substitutes for reality. Romance can function similarly, but specifically about the anxiety of human connection.

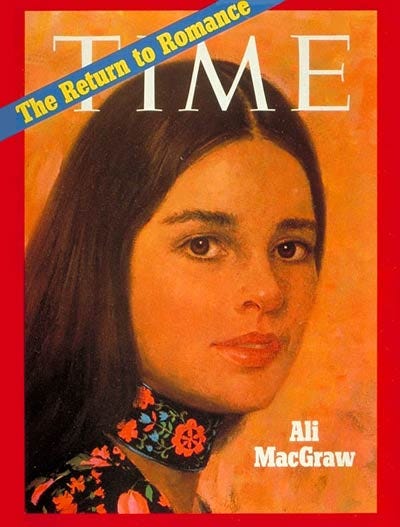

In a profile in Time Magazine, with the cover and title “A Return to Romance,” MacGraw and Love Story are both positioned in opposition to “contemporary” film and stars. Like Jenny, MacGraw is a secret font of nostalgia and connection to a bygone time: “Ali…represent[s] a return to something basic in the U.S. cinema. To a fresh flowering of the romance and sentimentalism of the ’30s and ’40s.” To be romantic is to be nostalgic for and connected to a past and this framing of MacGraw’s career is consistent, whether it is a compliment or a dig.

In the New Yorker review, Kael likens MacGraw’s marriage to Robert Evans, Paramount producer, to Norma Shearer’s marriage to Irving Thalberg, a former head of MGM, though she does so to besmirch both MacGraw and Shearer’s talents, though linking MacGraw with a past age of Hollywood. Another connection between the two actresses drawn by Kael is that Shearer handpicked Evans to play Thalberg in Man of a Thousand Faces, a 1957 biopic of Lon Chaney, starring James Cagney. But the Time feature frames this connection as a romantic throwback to Old Hollywood power couples.

Though the feature is a profile of MacGraw, it connects other aspects of the film to a backward-looking, reactionary world. The section of the Time article about the publishing of the book and the industry’s response shows the reactionary moment that the 1970s will be to the civil progress that we associate with the 1960s. Strome Lamon, an advertising director for Simon & Schuster, said “I think black study books and Women’s Lib books have shot their wad…The kids want romance. They’re discovering again that going to college is a wonderful little world. I can see them bringing back the Homecoming Queen and the pantie raids.” James Silberman, editor-in-chief at Random House said it even less delicately: “People are tired of reading about drugs and blacks. These books don’t have the same chic any more.” These quotes are hateful and gross, but they speak to something often elided in the history of romance, because it reveals something itself less romantic or politically satisfactory about the machine that gets books published.

The article points to the assassination of JFK as a moment of “cooling” for romanticism, when romantic things became ironically “camp.” The popular advent of TV meant old movies, including those that Ali MacGraw supposedly could fit right into, were scaled down and “a kid could safely dig Bogart’s telling Sam to play As Time Goes By without being accused of emotionalism.” The distance that allows for romanticism in the cynical 1960s could come from the art being created in the literal past or just set there: “sentiment, no matter how florid, was permissible it it was ancient.”14 This is born out in the two biggest romantic stories of the past decades, outside the genre fiction paradigm: Doctor Zhivago (published in 1957, but adapted for film in 1965) and The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1969), are both period pieces. So when romanticism returns in earnest in the 1970s, it retains that backward looking tilt, even when set in the 1970s (and adjacently, opens the door to a boom of historical romances in the 1970s.)

Love Story, the article posits, would have been rejected whole sale in 1969 seems like an inevitable trend in 1971. “Romance” was back in a big, reactionary way and we see this in the publishing history as well, even if is not directly an effect of Love Story’s success. The boom of romance publishing single-title paperbacks that everyone cites nearly at the same moment. In The Romance Novel in English: A Survey of Rare Books by Rebecca Romney, the books in the decade prior to Love Story and The Flame and the Flower come in a few varieties. There are category romances focused on careers, sweet Harlequin Romances (distinct from Harlequin Presents, a steamier line that started in 1973) and Gothics. All of these book were typified by minimal physical affection on page and a general lack of emphasis on any one author, focusing instead on the consistency of product within the line.

Interest in romance at a high point and a low tide of censorship (a benefit of those conflict-oriented 1960s and the Warren court) are aligned, so by the early 1970s, we can get sweeping romances with sex on page. In 1971, Nancy Coffey, editor at Avon, picks The Flame and the Flower by Kathleen E. Woodiwiss out the slush pile and the bodice ripper is a phenomenon by 1972. The Flame and the Flower is three times as long as a category and has include sex on the page. Romney points out another distinction I had never thought of: The Flame and the Flower was also originally as a paperback, signaling its links to genre fiction. This distinguishes it from ancestors of the genre like Forever Amber and Gone with the Wind, published originally as hardcovers and marketed as historical epics. Even Love Story was originally published as a hardcover.

As far as I can tell, the connection between Love Story’s moment and the boom of romance that follows goes nearly totally unexamined in romance history and criticism. Jenny’s death disqualifies Love Story from being thought of as a romance novel in retrospect from 2025. But in 1970, the genre as Genre is still developing. Romance Writers of America, with their proliferation of a top-down definition, won’t be founded for another decade. And that happily-ever-after mandate just isn’t as pervasive in the early decades of the genre.

Kristen Ramsdell mentions Love Story, film and book, in her book Happily Ever After: A Guide to Reading Interests in Romantic Fiction from 1987 under the sub-category “Soap Opera”15 as a type of Contemporary Romance. She defines them as “essentially complex, introspective, often many-peopled stories that revolve around the difficulties of a particular individual, family, or town. A love story usually figures prominently in the plot, but there are also a number of other sufficiently anguishing aspects...Suffering, affliction, illness, sin, revenge, and retribution permeate the plots, and happy endings are not a foregone conclusion.”

Ramsdell acknowledges here a history of classing things as romance that do not have HEAs—she keeps up this mantel until at least 1999, when she wrote in Romance Fiction: A Guide to the Genre: “Another criterion for romance fiction is the Satisfactory Ending. Usually, but not always, this is the traditional happy one, with the two protagonists forming some kind of committed relationship (usually marriage) by the book's conclusion.” The other mentions I see of the book are in writing guides for romance authors—one from 2006 even cites Oliver as an ideal hero!16

Angela Toscano gathered definitions of romance in reverse chronological order here and the earliest one that she lists is from 1976. In Adventure, Mystery, and Romance, John Cawelti, genre author himself who is arguing for genre fiction’s place amongst high literature, says “Though the usual outcome is a permanently happy marriage, more sophisticated types of love story sometimes end in the death of one or both of the lovers, but always in such a way as to suggest that the love relation has been of lasting and permanent impact. This characteristic differentiates the mimetic form of the romantic tragedy from the formulaic romance.”17 While Love Story might not be considered a romance novel today, it would have been under these past definitions.

This hole in the discussion reminds me of what I saw during the Duke Project, when authors and critics talked about Dukes as a parallel to billionaires, and pointed to the 2007-2008 financial crisis as a reason for the boom for each. instead of talking about Fifty Shades of Grey, which matches the boom’s timeline more (going viral in 2012). There can be more than one proximate cause for a trend, but it is disingenuous to ignore a story as big as either Love Story or Fifty Shades of Grey was as one of the factors. The writing and success of Fifty Shades of Grey could have also been connected to the financial crisis, but the surfeit of billionaire (and possibly duke) romances that followed surely was amplified by that viral success.

Love Story may not have caused Avon to take a risk on romantic epic with sex on the page in the slush pile, but Love Story succeeded in a market and further primed a country for more romantic content, particularly after a period when the country was in a drought of such stories, outside the more niche market of categories.

So I think how Love Story is discussed, both the immediate reaction and the historical memory of it, parallels romance in ways, but given the ubiquity of the story, this is a piece of media certainly consumed by a generation of authors and readers who are so important to the history of romance. With all the necessary caveats about book sales numbers being spurious, Love Story on its own, a single title, is given the number of 21 million books sold. The number I see most often for Colleen Hoover, the author most associated with virality and staggering book sales in the 2020s, is 20 million (in 2022, so maybe she’s exceeded Love Story now with her 11 New York Times Best Sellers). When Pauline Kael disparages Love Story readers as the type to “rarely read anything in hard covers,” she means its readers are paperback (and probably romance) readers.

Susan Elizabeth Philips, one of the only contemporary authors I consistently enjoy, related her experience of reading the book to NPR on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the film:

"I remember when I read it, of course dissolving in tears," says Phillips. "I read it to my boyfriend at the time, read it out loud to him, sobbing through the whole thing. We've now been married for 50 years." Phillips says her husband doesn't remember any of this. "So that's a blessing," she jokes.

SEP is right around Jenny Cavilleri’s age, 22 in 1970. My mother was 10 when the film came out and she showed it to me when I was 10. I think it’s the perfect age to experience something maudlin and schlocky and romantic and simple, all of which I mean positively. Sometimes people frame Love Story the way they frame so much of romance, as escapist, as worthy only of a mechanism for turning your brain off and shutting down the outside world. But I’m skeptical of any argument for the popularity of a romance or a romantic story that is based on its readers or viewers being interested in getting dumber or more numb to the world, even as I see readers framing their consumption of these stories as “turning off their brain.”

Love Story does not have a happily-ever-after, but it’s a book and film that shaped one generation of readers and movie viewers. Many of the derisive film reviews suggest the worst thing in the world that could happen post-Love Story would be a bunch of imitations of it. Takes with any retrospect acknowledge that this didn’t really happen. Watching in theaters last week, I don’t know how it could have, at least in the film medium.18 O’Neal and MacGraw’s chemistry is so singular. I’m not using this word to say that it is great, but different than anything I’ve ever seen. The false bite of her attempts at cursing, his emotional outbursts, both positive and negative, that come out of nowhere. All that phoniness that Pauline Kael hated. But also when she takes a bite of snow off his face when they are making snow angels on the Harvard football field. But I can see an audience watching this and then craving books that sweep them in the same way.

I’ve seen this movie probably every couple of years since I was 10. I cry the same amount every time. It always works on me, even as I get (hopefully) smarter and (depressingly) more cynical. There have been times watching it where I felt like Vincent Canby, throwing up my hands, saying “it’s stupid, but it worked!” Or I felt like a viewer that Kael would deride: “I’m stupid because it works on me.” But looking at the movie in terms of romance, as manifestation of popular fiction demands from 1970, responsive to the crowd in the way that genre fiction has a history of being, I feel most aligned with Roger Ebert’s take: why not take it on its own terms? It’s a weepy melodrama, measure it as such. And, frankly, despite my caveat the beginning of this newsletter, I’ve also convinced myself: It is a romance novel. Dying and beautiful Ali MacGraw and all.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-crossed lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Doth with their death bury their parents’ strife.

The plot of Love Story, if you need it: The action fades back to Oliver and Jennifer’s meeting at Radcliffe’s library. He’s a preppie jock from Harvard, she is a music major from a working class background. They’re both stunning beautiful. Oliver, big man on campus, is taken with Jenny quickly, partially because she plays hard to get and seems to not fall for his line immediately. But in a rainy confrontation scene, she declares she cares as much as he does. They have sex. This all happens in the first twenty minutes.

Jenny has a scholarship offer to study music in Paris after graduation and when Oliver finds out, he proposes so that’ll she stay. He’s going to stay in Cambridge for Harvard Law School. This is never characterized as manipulative—Jenny’s enthused by the prospect. Oliver’s parents are not. Oliver Barnett III tells Oliver in no uncertain terms that support for Oliver’s law school will be taken from him if he and Jenny marry. The couple marries and lives an idyllic three years together in a fourth-floor walk up and working part time jobs to make ends meet. They have one fight about Oliver’s parents (Jenny thinks he should reach out to them after a few years of silence) and this where we get “Love means never having to say you’re sorry” from Jenny when Oliver apologizes for storming out on her.

Oliver graduates third in his class and gets a job working at a large law firm in New York. The couple nests, but struggles to get pregnant, prompting them to a visit a doctor. When Oliver visits, the doctor tells him that Jenny’s test results indicate that she is dying. No further details are given, except that Oliver is not supposed to tell Jenny. Eventually, Jenny follows up with the doctor herself and learns the news. Oliver goes to his father to ask for money for the treatment, but his father assumes he is asking for money for an abortion of a mistress. When Oliver returns to Jenny’s bedside, she has grown weaker incredibly fast and she dies in Oliver’s arms. His father meets him outside the hospital, having called around and found out about Jenny. He begins to apologize, but Oliver interrupts him and repeats “Love means never having to say you’re sorry,” walking away to the ice skating rink where we found him at the beginning of the film.

Author bio at Vasvari’s blog, Somewhere Becoming Rain.

Suggesting that whether 1970 Ali MacGraw is beautiful is a “matter of taste” makes me see red.

Pauline Kael points out in her New Yorker review that MacGraw mispronounces “Köchel.” I have to give that one to Kael, though I hate this line in her review on Ali MacGraw, referencing her earlier role in Goodbye, Columbus: “She isn’t supposed to be a bitch this time, and from some angles she doesn’t look so good, either.”

I don’t think either of these things are true. Though that may be my 2025 brain looking at any movie from the 1970s. Movies now are terribly shot and poorly edited.

The “famous fan” that Rubenstein is referring to is Barbara Walters, who, on Valentine’s Day morning in 1970, said of Erich Segal’s book “I was up most of the night reading a book I couldn’t put down, and when I finished it, I was sobbing. I cried and cried.”

I thought it was notable how almost none of the contemporary reviews that I read mention Jenny’s clothes, which I consider the stand-out feature of the film, even above other features from the period. Pauline Kael does wonder how a working-class girl affords that camel coat (that I am so envious of).

The commenters on Ebert’s website, where his archived reviews have been reposted, cannot believe that he gave this movie four stars, despite explaining why he did so, I think, pretty clearly. One commenter felt the need to describe it as “sadstrubation” in two different comments.

Interesting in the world of elites that we’re occupying here: Canby and William Styron were close childhood friends. William Styron was on the committee for the 1970 National Book Award that threatened to resign if the novel Love Story remained on the short list.

The last three these movies are all certainly much better films than Love Story.

I tried to figure out the timeline of Love Story with Oliver’s implied deferment. His student status as a undergrad and then law student would have protected him until 1971, but we leave he as a young associate at a law firm in New York in winter 1970, if the movie is set when it was released. I think he would have been included in the lottery held on December 1, 1969.

In the 1971 Virginia Slims American Women's Opinion Poll, women “rejected the midiskirt length by a thumping 65 to 32 per cent, and endorse the old‐fashioned mini by 59 to 39 per cent.” Reported in The New York Times

The author cites The French Lieutenant’s Woman by John Fowles, which I think I should read. I imagine it, like Love Story, had an impact on genre romance, as one of the best selling books of 1969. And it’s a historical.

This nomenclature is slightly bizarre to me, though Ramsdell explains that she identifying a pattern that comes from earlier, though the name comes from the detergent commercials that would play during radio and television shows in the genre.

Writing the Great American Romance Novel, Catherine Lanigan, 2006

Adventure, Mystery, and Romance, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

The one film that I can think of that feels like Love Story is The Way We Were from 1973.

My experience of the Crimson Key screening of Love Story was that it just felt mean in an unproductive way - I think by the time I was a freshman at Harvard, thanks to Facebook and memes, everyone was fully aware of the contradictory meanings Harvard-as-a-brand held, and even people enamored with the institution knew they were being a little bit cringe about it. But being cruel about the saccharine bourgeois nature of the film during freshman orientation didn't reveal anything to me about the social fissures of the campus in the late 2010s (or about it in the late 60s), and Ali MacGraw is simply too beautiful to believe the jeers! There's still a lot to think about in how Harvard gets depicted here, though, particularly in how the Radcliffe vs. Harvard thing plays out on screen (part of the reason Oliver gets teased by his roommates is that Harvard men in this era didn't date Cliffies; they went out to Wellesley or even Smith instead), and overall the film's resistance to really thinking about gender relations is notable! I think the absence of women's lib is almost as glaring as the absence of Vietnam, actually. I think I caught the same PFS screenings that you did and what stood out to me as an adult and not a college freshman is how obviously smarter and more interesting Jenny is than Oliver, how willingly Jenny gives up her fellowship to France to marry Oliver, how quickly she becomes a housewife and a wannabe mom despite her little quips of the first ten minutes, and how the film's romantic sappiness necessarily negates the intellectual feminist vibrancy that she could otherwise have had. I still cried at the end but I'm not so sure it was because I was sad about Jenny's death but rather I was saw about the person she could've been without him, if that makes sense. Anyway! That's just some thoughts I've been having. I really liked this essay thanks for writing it

I was going to mention having a similar experience watching The Way We Were (sobbing uncontrollably)!

This piece makes me curious about the costume designer’s choices for Jenny’s wardrobe. Costuming is so important to the storytelling and I love when we can get a peak at the designer (or department’s) vision and process.